2015

T. S. Eliot Prize

Winner

The Chair of the judges’ speech

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘It is thrilling to read a debut collection as exciting and ambitious as Loop of Jade. Sarah Howe brings new possibilities to British poetry, with her scholarly but intimate explorations of her Anglo-Chinese heritage. The poem ‘Tame’ confronts gender inequality in the Chinese preference for boys, with its devastating tale of a newborn daughter’s face pushed into ashes. Loop of Jade is sophisticated, erudite, packed with inexhaustible treasures, but it’s the power of Howe’s image-making, especially in the title sequence, that lingers in my mind. Images such as ‘cockroaches, like obscene sucked sweets’ are indelible, as are her daring experiments with form and adroit use of white space to convey what is unsayable.’ – Pascale Petit, Chair

Good evening. It’s been a privilege to judge the T. S. Eliot Prize, and close-read such wonderful books, considerably helped by my fellow judges Kei Miller and Ahren Warner. This is a fantastic time for poetry, with the highest amount of entries submitted in the history of the prize, and an exceptional number of outstanding collections, including stunning debuts.

I’m going to talk about the ten shortlisted collections in alphabetical order of the poets’ names.

Mark Doty’s Deep Lane mines the ‘anvil of darkness’, delving into an earthy underworld to bring back poems shining with transcendence and ‘the wild unsayable’, where radishes turn into ‘two impossible bundles of thunder’. This is a collection to keep returning to for sheer joy, full of rapture for words, the pulse of life and the sensory realm. The long poem ‘King of Fire Island’, where the creaturely and human merge in the apparition of a lame stag, is a tour de force. There is tenderness throughout for the vulnerable denizens of this planet and the immanence beneath everyday surfaces.

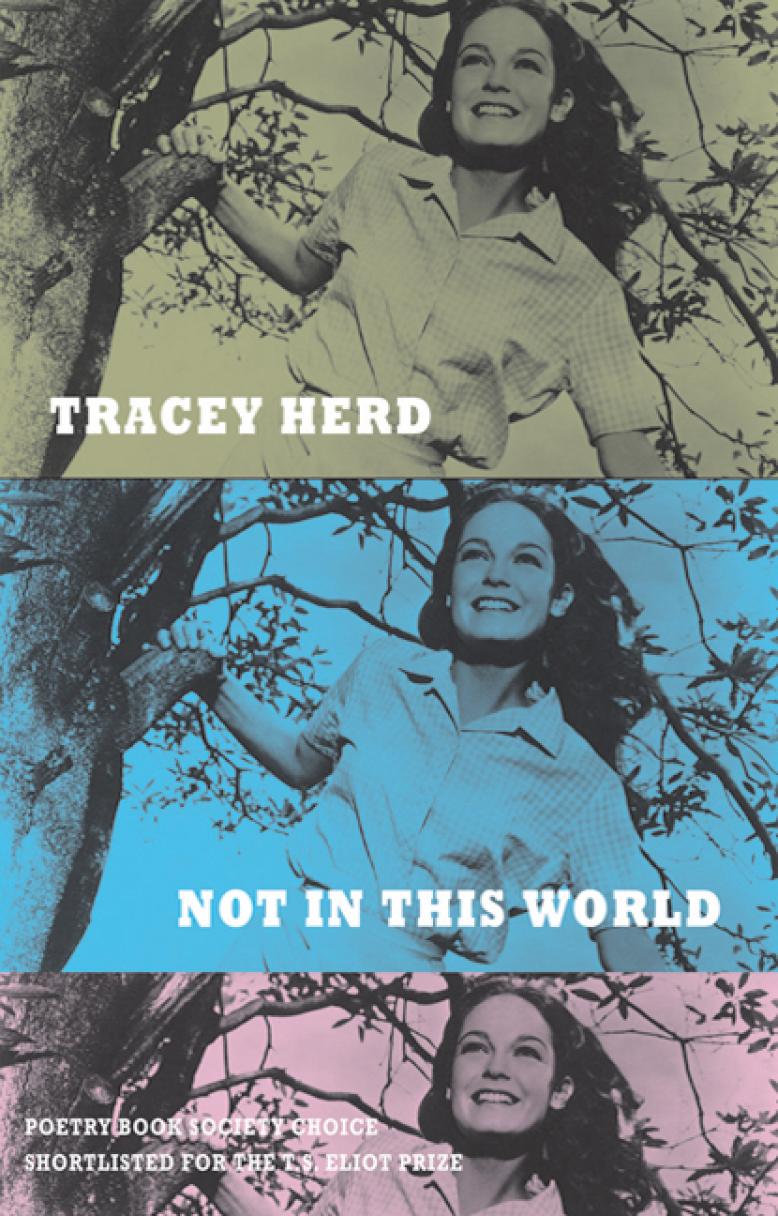

The poems in Tracey Herd’s Not in this World are harrowing, as if sculpted with an ice-pick in the glaciers of depression. Yet the ice is fiery, survival is at stake in an unsentimental world, where the diction is as rigorous as the gaze. There are Hollywood starlets, Ruffian the racehorse, and self-portraits where Herd confronts her own demons. Heart-breaking lines, such as ‘look at you lying there in your little glass coffin, / or is it a snow globe? Were you terribly cold? / Will I sprinkle your cradle with snow?’ from the poem ‘Happy Birthday’, conjure a world pared to the bone. It is rare to come across lines as stripped and taut as hers.

Selima Hill’s Jutland has an astounding vivacity. Hill is a complete original whose body of work is unique in British poetry and this volume is an example of her at her best. Jutland consists of two extended sequences: ‘Advice on Wearing Animal Prints’, a kaleidoscope of shifting perspectives presenting the character Agatha, and ‘Sunday Afternoons at the Gravel-Pits’, portraying a little girl and her father. Each poem tells an uncomfortable truth, through fireworks of surreal images. Every image is a surprise, sometimes funny, usually shocking, but at the same time archetypal as a brand new fairy-tale, and all this is achieved with crystalline brevity.

It is thrilling to read a debut collection as exciting and ambitious as Loop of Jade. Sarah Howe brings new possibilities to British poetry, with her scholarly but intimate explorations of her Anglo-Chinese heritage. The poem ‘Tame’ confronts gender inequality in the Chinese preference for boys, with its devastating tale of a newborn daughter’s face pushed into ashes. Loop of Jade is sophisticated, erudite, packed with inexhaustible treasures, but it’s the power of Howe’s image-making, especially in the title sequence, that lingers in my mind. Images such as ‘cockroaches, like obscene sucked sweets’ are indelible, as are her daring experiments with form and adroit use of white space to convey what is unsayable.

Tim Liardet’s The World Before Snow is an extended sequence about a mid-life love affair begun in America during a blizzard. These intense long-lined verses freeze the chance encounter in cubist arrangements played out in echo chambers and halls of mirrors, as the lovers adjust to their new situation. The lyric line is stretched to accommodate their instability, as images become more fractured. This technique brilliantly succeeds in describing the aftermath of one meeting, each moment in the process of exploding, like Cornelia Parker’s exploding shed in her installation ‘Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View’. Like Parker, Liardet immerses us in an installation of momentous force.

Les Murray’s Waiting for the Past has his legendary sprawl but it’s compressed into compact verses. He writes the nakedly intimate and the cosmic grand and both can inhabit the same line. His imagination leaps from the mundane to the vast and spans millennia with ease – a coal age can form in one afternoon. He has a genius for dazzling metaphors – a constellation is ‘long spittle / streaks from dark iron jaws’. Foliage is ‘the blind computer [that] plays between core and star’. His linguistic callisthenics are breathtaking, as is the sheer range of his themes. Waiting for the Past is fresh as a child’s painting book and brimming with wisdom and integrity.

Sean O’Brien’s The Beautiful Librarians also has an astonishing range but paints a darker world than Murray’s, delivered in a passionate robust metre. Though O’Brien makes damning social critiques, some are poems of apocalyptic vision, such as ‘Wedding Breakfast’. Along with his satire there is humour and tenderness, with images surreal as a bride in her snow gown and her coalman groom. These fantastical and realist social critiques are counterbalanced by the beautiful librarians of the title poem, a hymn to libraries, women and to the power of art, and it is these elegies to what is passing and lost that gives this book its tragic undertone.

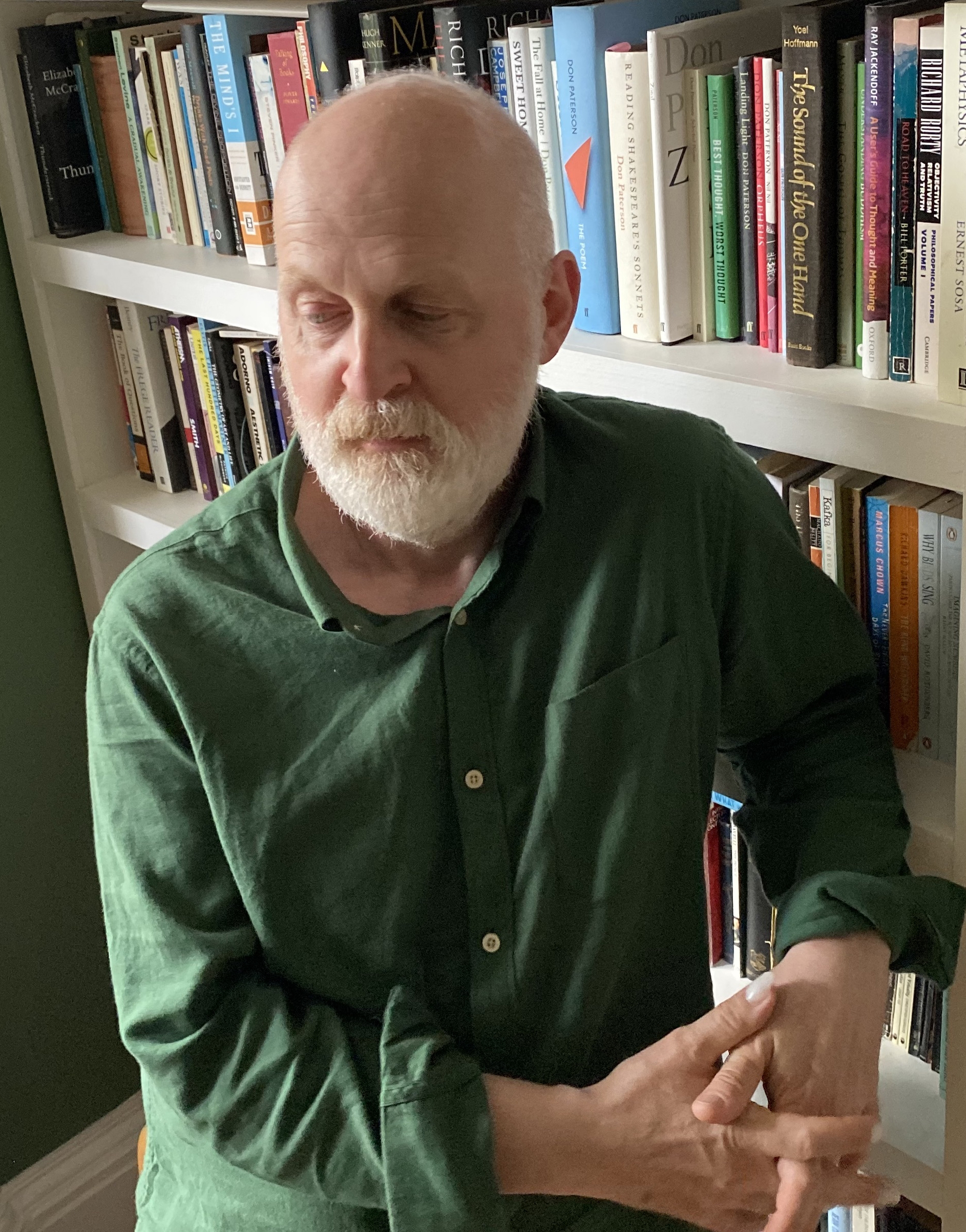

It is no surprise that Don Paterson, who gave us eloquent commentaries on Shakespeare’s sonnets, and consummate versions of Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus, is a master craftsman of the form. Each poem in 40 Sonnets achieves its virtuoso effects by sleight of hand, all artistry invisible and apparently effortless. Like Shakespeare, the music of the line carries the meaning before it. Beyond the artistry, what is striking, and makes this book extraordinary, is how deeply it delves into the paradoxes of the human condition, making straight to the heart of our humanity; each poem rings true.

Rebecca Perry is our second thrilling debut. In Beauty/Beauty, she offers female perspectives with openness and vulnerability, in both her themes and experiments with form, to find new ways of writing the feminine. Non-linear images are subverted by shattered narratives, in poems written ‘from the nose / out, like a painting’. Her gaze is not limited to personal experience. It is a triumph of imagination that she is able to empathise with other forms of oppression, such as the killing of Bigfoot and a slave on a slave ship. She captures the sadness of seas and writes a love poem to a stegosaurus, whose mouth ‘holds more wonder than a sky full of stars’.

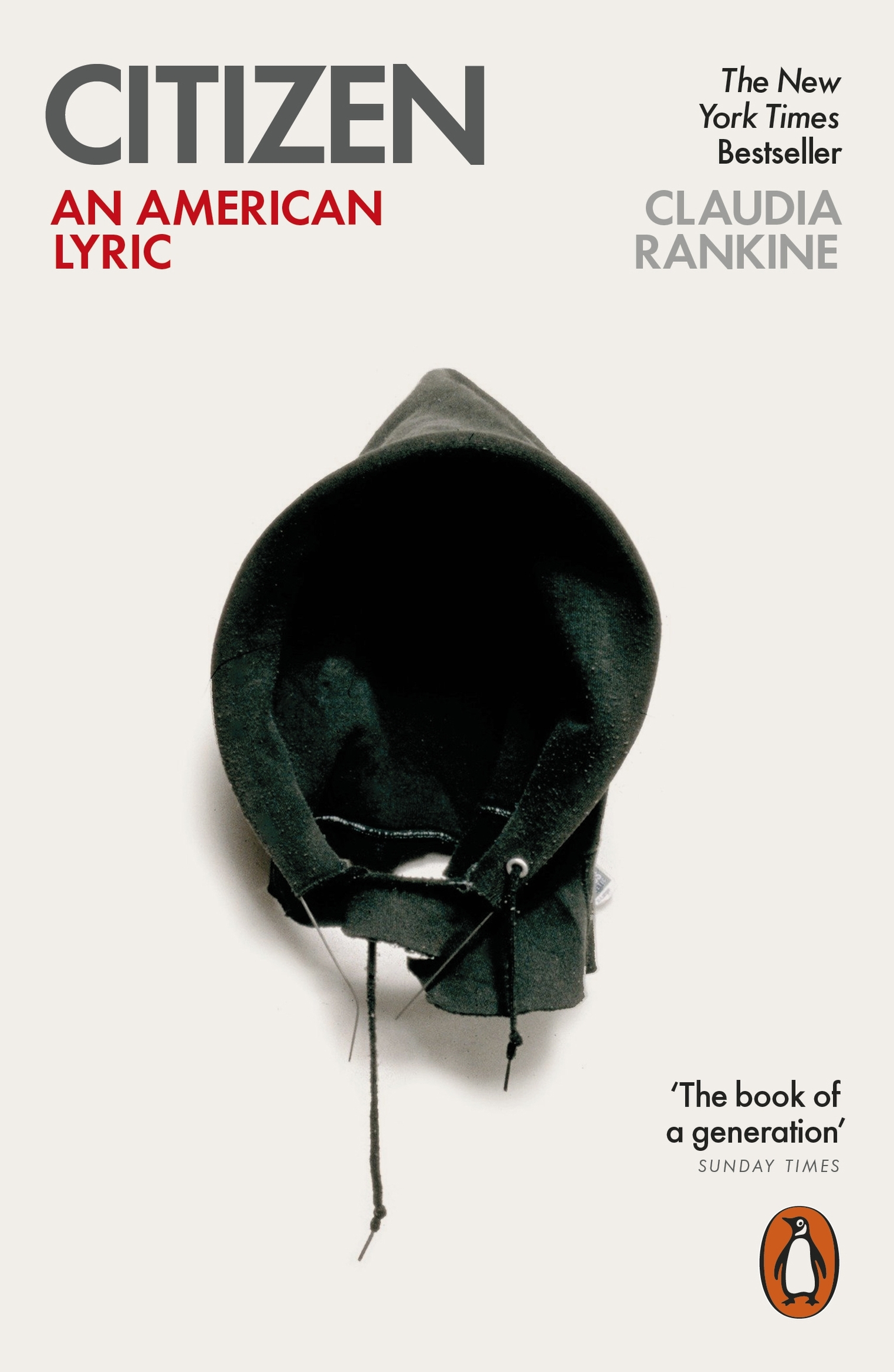

Claudia Rankine, in Citizen: An American Lyric, reinvents poetry, as we know it, with its collage of lyric essays, scripts for situation videos, vignettes, poems and screen-grabs. Each word cuts with forensic precision, shorn of ornament, and the writing is punctuated by quality art images that allow breathing space. The theme of the ugliness of racism is urgent, and crafted into a compelling read. With the ‘you’ address, as readers, we each experience the harm of micro-aggressions and not so micro- acts of everyday inequality. We understand and feel racism’s destructive effects on a cellular level. The result is unforgettable and utterly necessary.

These ten books are all strong contenders and we had a very tough decision to make.

The winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize for Poetry in 2015 is Sarah Howe for Loop of Jade.

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘It is thrilling to read a debut collection as exciting and ambitious as Loop of Jade. Sarah Howe brings new possibilities to British poetry, with her scholarly but intimate explorations of her Anglo-Chinese heritage. The poem ‘Tame’ confronts gender inequality in the Chinese preference for boys, with its devastating tale of a newborn daughter’s face pushed into ashes. Loop of Jade is sophisticated, erudite, packed with inexhaustible treasures, but it’s the power of Howe’s image-making, especially in the title sequence, that lingers in my mind. Images such as ‘cockroaches, like obscene sucked sweets’ are indelible, as are her daring experiments with form and adroit use of white space to convey what is unsayable.’ – Pascale Petit, Chair

Good evening. It’s been a privilege to judge the T. S. Eliot Prize, and close-read such wonderful books, considerably helped by my fellow judges Kei Miller and Ahren Warner. This is a fantastic time for poetry, with the highest amount of entries submitted in the history of the prize, and an exceptional number of outstanding collections, including stunning debuts.

I’m going to talk about the ten shortlisted collections in alphabetical order of the poets’ names.

Mark Doty’s Deep Lane mines the ‘anvil of darkness’, delving into an earthy underworld to bring back poems shining with transcendence and ‘the wild unsayable’, where radishes turn into ‘two impossible bundles of thunder’. This is a collection to keep returning to for sheer joy, full of rapture for words, the pulse of life and the sensory realm. The long poem ‘King of Fire Island’, where the creaturely and human merge in the apparition of a lame stag, is a tour de force. There is tenderness throughout for the vulnerable denizens of this planet and the immanence beneath everyday surfaces.

The poems in Tracey Herd’s Not in this World are harrowing, as if sculpted with an ice-pick in the glaciers of depression. Yet the ice is fiery, survival is at stake in an unsentimental world, where the diction is as rigorous as the gaze. There are Hollywood starlets, Ruffian the racehorse, and self-portraits where Herd confronts her own demons. Heart-breaking lines, such as ‘look at you lying there in your little glass coffin, / or is it a snow globe? Were you terribly cold? / Will I sprinkle your cradle with snow?’ from the poem ‘Happy Birthday’, conjure a world pared to the bone. It is rare to come across lines as stripped and taut as hers.

Selima Hill’s Jutland has an astounding vivacity. Hill is a complete original whose body of work is unique in British poetry and this volume is an example of her at her best. Jutland consists of two extended sequences: ‘Advice on Wearing Animal Prints’, a kaleidoscope of shifting perspectives presenting the character Agatha, and ‘Sunday Afternoons at the Gravel-Pits’, portraying a little girl and her father. Each poem tells an uncomfortable truth, through fireworks of surreal images. Every image is a surprise, sometimes funny, usually shocking, but at the same time archetypal as a brand new fairy-tale, and all this is achieved with crystalline brevity.

It is thrilling to read a debut collection as exciting and ambitious as Loop of Jade. Sarah Howe brings new possibilities to British poetry, with her scholarly but intimate explorations of her Anglo-Chinese heritage. The poem ‘Tame’ confronts gender inequality in the Chinese preference for boys, with its devastating tale of a newborn daughter’s face pushed into ashes. Loop of Jade is sophisticated, erudite, packed with inexhaustible treasures, but it’s the power of Howe’s image-making, especially in the title sequence, that lingers in my mind. Images such as ‘cockroaches, like obscene sucked sweets’ are indelible, as are her daring experiments with form and adroit use of white space to convey what is unsayable.

Tim Liardet’s The World Before Snow is an extended sequence about a mid-life love affair begun in America during a blizzard. These intense long-lined verses freeze the chance encounter in cubist arrangements played out in echo chambers and halls of mirrors, as the lovers adjust to their new situation. The lyric line is stretched to accommodate their instability, as images become more fractured. This technique brilliantly succeeds in describing the aftermath of one meeting, each moment in the process of exploding, like Cornelia Parker’s exploding shed in her installation ‘Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View’. Like Parker, Liardet immerses us in an installation of momentous force.

Les Murray’s Waiting for the Past has his legendary sprawl but it’s compressed into compact verses. He writes the nakedly intimate and the cosmic grand and both can inhabit the same line. His imagination leaps from the mundane to the vast and spans millennia with ease – a coal age can form in one afternoon. He has a genius for dazzling metaphors – a constellation is ‘long spittle / streaks from dark iron jaws’. Foliage is ‘the blind computer [that] plays between core and star’. His linguistic callisthenics are breathtaking, as is the sheer range of his themes. Waiting for the Past is fresh as a child’s painting book and brimming with wisdom and integrity.

Sean O’Brien’s The Beautiful Librarians also has an astonishing range but paints a darker world than Murray’s, delivered in a passionate robust metre. Though O’Brien makes damning social critiques, some are poems of apocalyptic vision, such as ‘Wedding Breakfast’. Along with his satire there is humour and tenderness, with images surreal as a bride in her snow gown and her coalman groom. These fantastical and realist social critiques are counterbalanced by the beautiful librarians of the title poem, a hymn to libraries, women and to the power of art, and it is these elegies to what is passing and lost that gives this book its tragic undertone.

It is no surprise that Don Paterson, who gave us eloquent commentaries on Shakespeare’s sonnets, and consummate versions of Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus, is a master craftsman of the form. Each poem in 40 Sonnets achieves its virtuoso effects by sleight of hand, all artistry invisible and apparently effortless. Like Shakespeare, the music of the line carries the meaning before it. Beyond the artistry, what is striking, and makes this book extraordinary, is how deeply it delves into the paradoxes of the human condition, making straight to the heart of our humanity; each poem rings true.

Rebecca Perry is our second thrilling debut. In Beauty/Beauty, she offers female perspectives with openness and vulnerability, in both her themes and experiments with form, to find new ways of writing the feminine. Non-linear images are subverted by shattered narratives, in poems written ‘from the nose / out, like a painting’. Her gaze is not limited to personal experience. It is a triumph of imagination that she is able to empathise with other forms of oppression, such as the killing of Bigfoot and a slave on a slave ship. She captures the sadness of seas and writes a love poem to a stegosaurus, whose mouth ‘holds more wonder than a sky full of stars’.

Claudia Rankine, in Citizen: An American Lyric, reinvents poetry, as we know it, with its collage of lyric essays, scripts for situation videos, vignettes, poems and screen-grabs. Each word cuts with forensic precision, shorn of ornament, and the writing is punctuated by quality art images that allow breathing space. The theme of the ugliness of racism is urgent, and crafted into a compelling read. With the ‘you’ address, as readers, we each experience the harm of micro-aggressions and not so micro- acts of everyday inequality. We understand and feel racism’s destructive effects on a cellular level. The result is unforgettable and utterly necessary.

These ten books are all strong contenders and we had a very tough decision to make.

The winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize for Poetry in 2015 is Sarah Howe for Loop of Jade.