2019

T. S. Eliot Prize

Winner

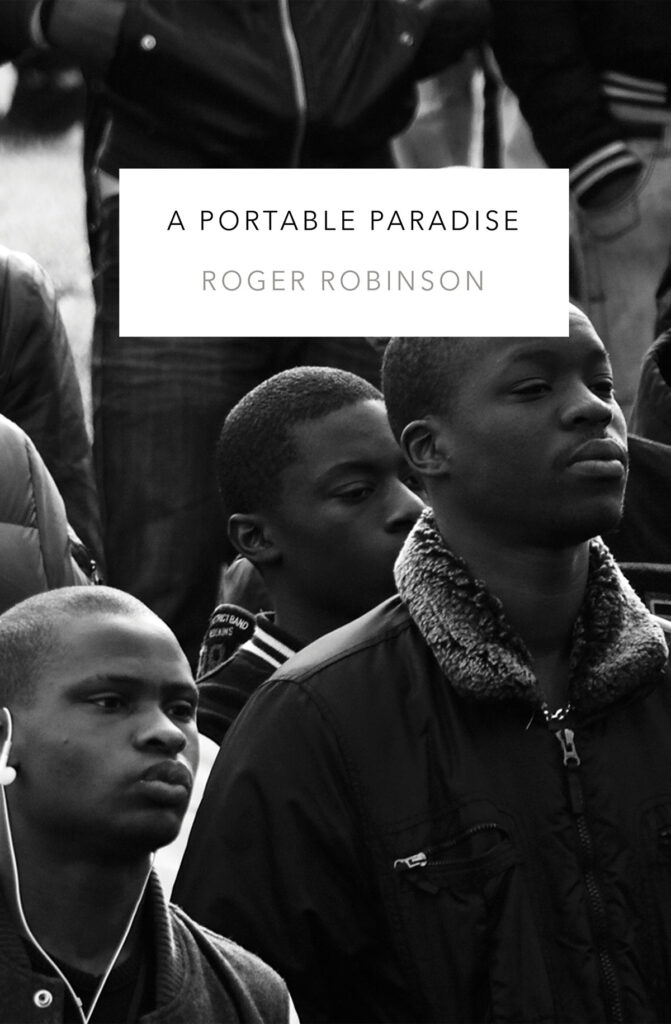

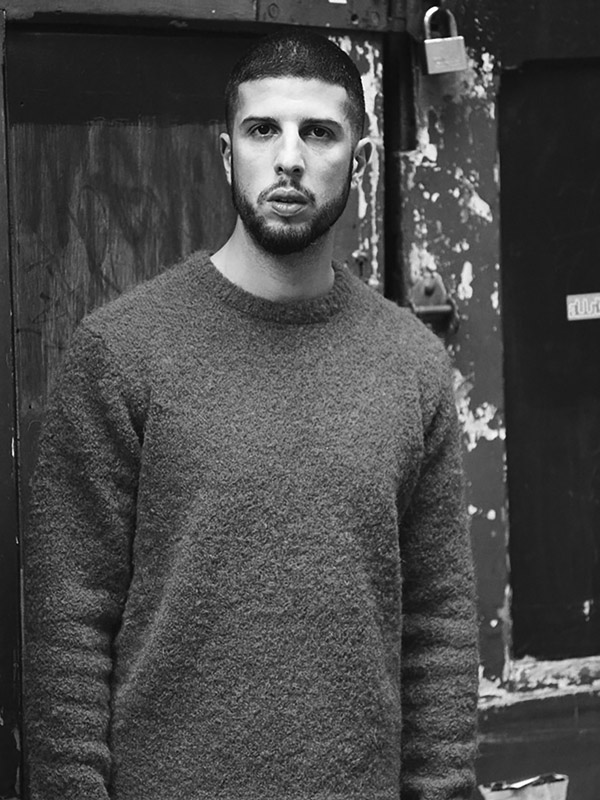

Roger Robinson is a writer and performer who lives in Northampton. His poetry pamphlet Suckle (flipped eye, 2009) won the People’s Book Prize and the Oxford Brookes Poetry Prize. His first full poetry collection, The Butterfly Hotel (Peepal Tree Press, 2013), was shortlisted for the OCM Bocas Poetry Prize and his second, A Portable Paradise (also Peepal Tree Press, 2019), won the T. S. Eliot Prize 2019 and the Ondaatje Prize 2020. Home Is Not A Place, his collaboration with the acclaimed photographer Johny Pitts, was published by William Collins in 2022. Roger Robinson is an alumnus of The Complete Works and was a co-founder of both Spoke Lab and the international writing collective Malika’s Kitchen. He has received commissions from the National Trust, London Open House, BBC, National Portrait Gallery, V&A, INIVA, MK Gallery and Theatre Royal Stratford East. Roger is a sought-after internationally-acclaimed writer, educator and workshop leader in poetry and has toured extensively with the British Council.

The Chair of the judges’ speech

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘Roger Robinson’s characters bear witness to a country where ‘every second street name is a shout out to my captors’. Yet though Robinson is unstinting in his irony, he also gives us glimpses of something that his chosen protagonists also refuse to surrender – a taste, through the bitterness, of ‘life, of sweet, sweet life’.’ – John Burnside, Chair

T. S. Eliot Prize 2019: the Chair of judges’ speech by John Burnside

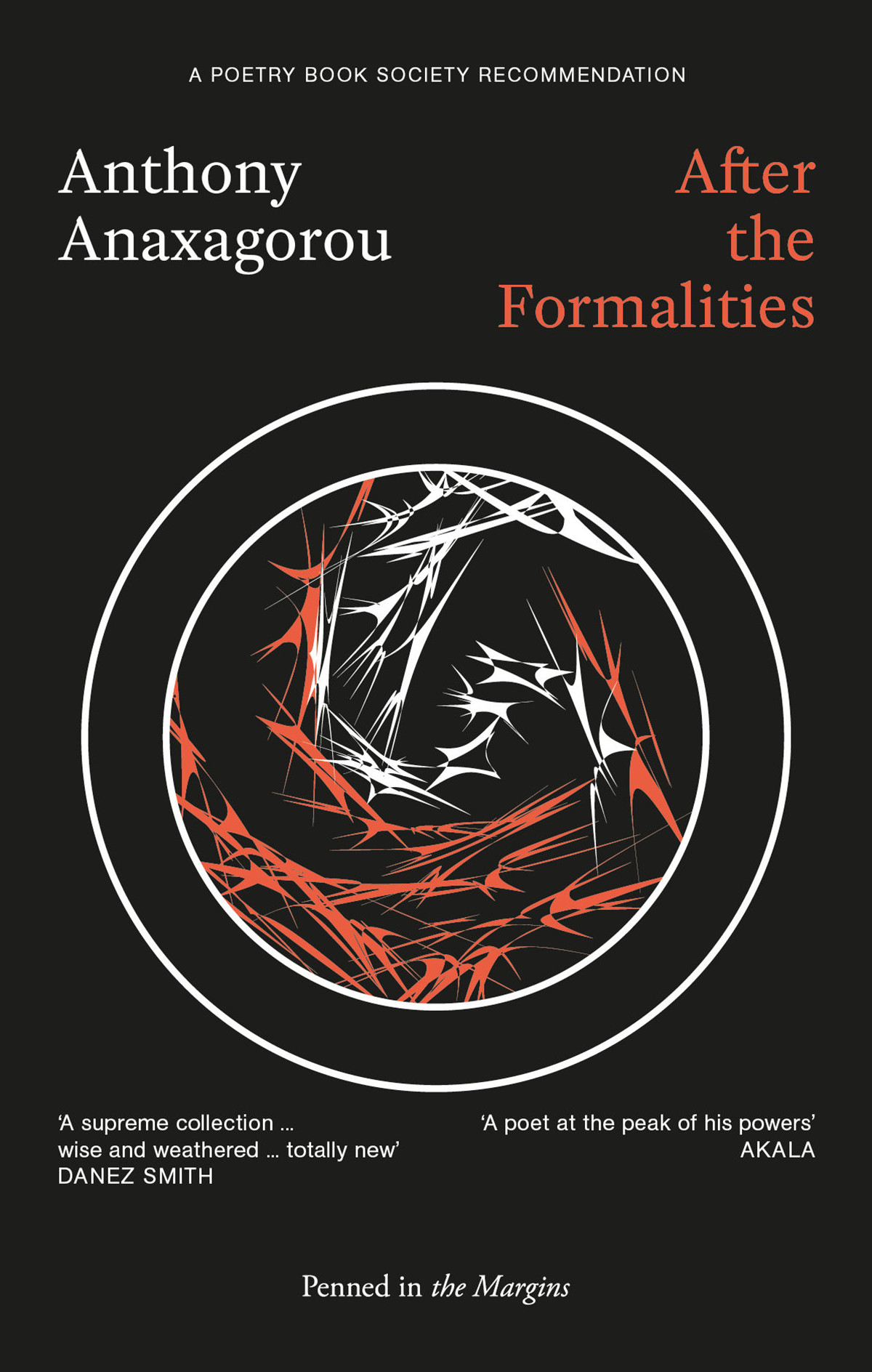

Anthony Anaxagorou – After the Formalities

If you are like me, you turn straight to the title poem in a collection, as I did with After the Formalities, to be drawn wholly and utterly into a poem of immense rhetorical and political power. Yet the book is full of such richness, with a wonderful tempered sense of history that comes of accommodating, but not ignoring, justifiable anger.

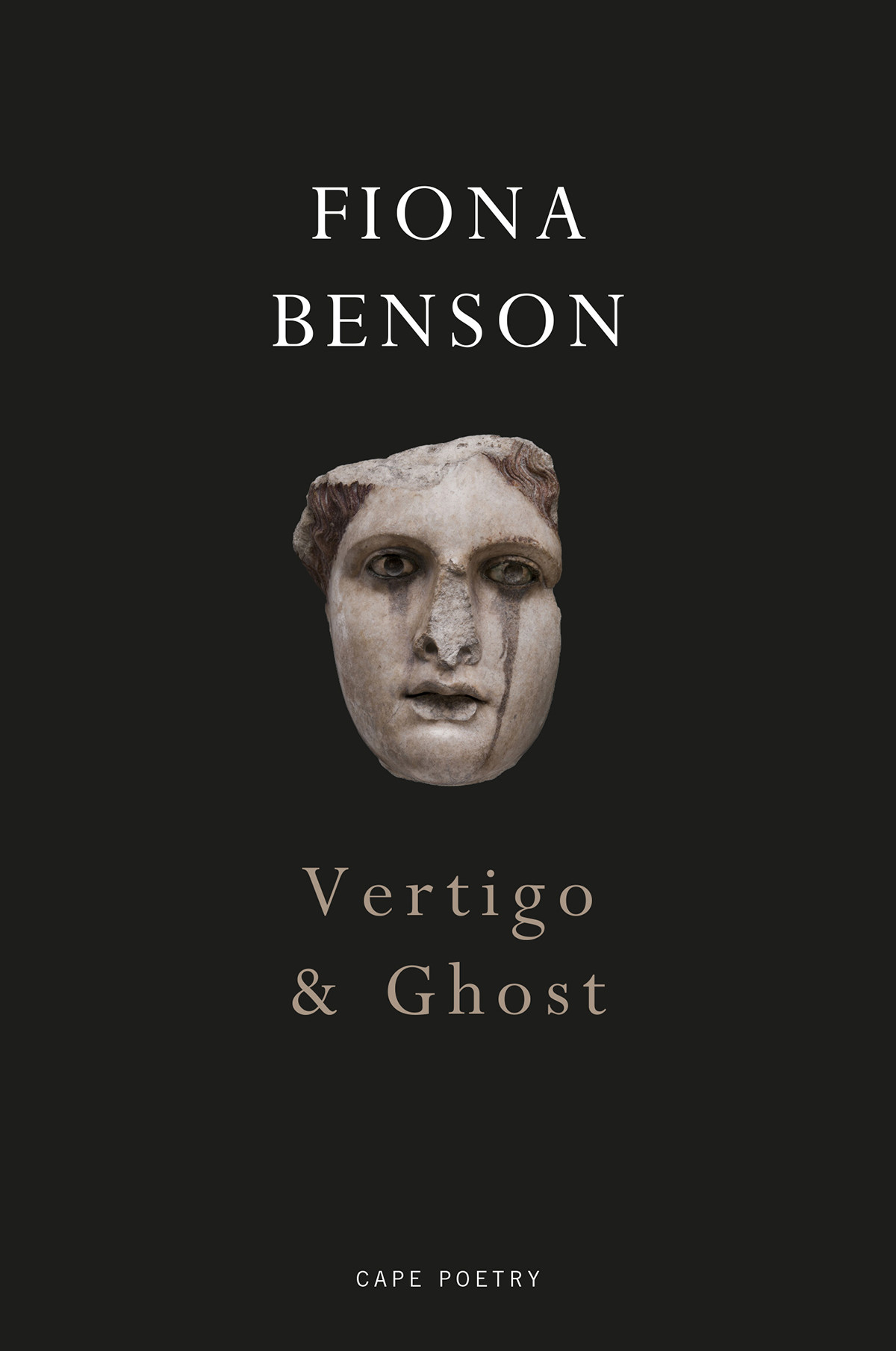

Fiona Benson – Vertigo & Ghost

When Fiona Benson gets after something, she does so with total commitment, like Kafka’s great trapeze artist, digging deep into the hurts and fears and tendresses that haunt us most, not because she is cruel, but because she knows that, if we are to live with monsters, we must pass through the place where they live and emerge, less innocent, but wiser, on the other side of fear.

Jay Bernard – Surge

In Surge, Bernard stands face to face with the full horror of the New Cross Fire, bringing a fierce sense of history and a powerful rhetorical gift to what could have been an overwhelming battle, transforming what might have been a howl of protest against many decades of racism and prejudice into an enduring testament to justice.

Paul Farley – The Mizzy

To open a collection by Paul Farley is a little like dipping into an illuminated manuscript from the rich Medieval era and yet it feels very local – local to specific places and times, local to a ‘certain patch of rocks between two sides’ and ‘the swing bridge at Preston Docks’ local to who, when and where we are, now, in our dreams and in our waking.

Ilya Kaminsky – Deaf Republic

Every now and then a new poetry appears that, even if it speaks your language, it nevertheless teaches us new terms, a new vocabulary. Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic is just such a poetry. Neither its pathos nor its cruelty are final – indeed nothing is, and if the question ‘What is a man?’ can be answered as ‘the quiet between two bombardments’ so the question ‘What is silence?’ can evoke the reply, ‘Something of the stars in us’.

Sharon Olds – Arias

By my count, Arias is Sharon Olds’s twelfth collection and in it we see a master poet at the full height of her powers. Who else would compare her speaker-self to ‘a seal sticking halfway out of the concave comber it is riding’? – and even exultant: as much celebration as elegy, even as, undeniably, it gives us some of the finest elegiac poems written in recent times.

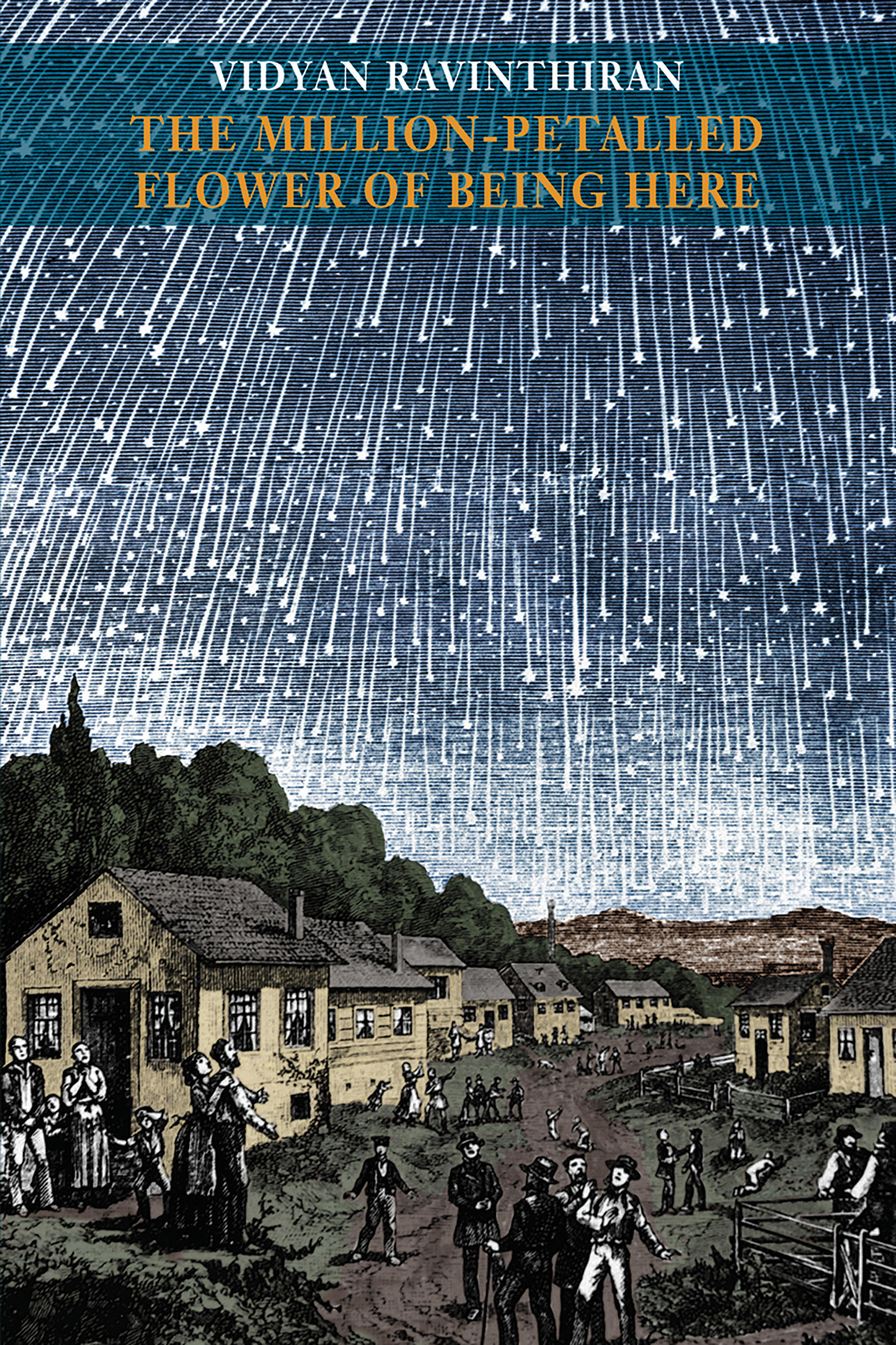

Vidyan Ravinthiran – The Million-petalled Flower of Being Here

To commit an entire collection to the sonnet is a brave act. It shows not just trust in one’s abilities but also a humility before the form that any kind of success demands. Few have achieved this is many years but The Million-petalled Flower of Being Here offers an object lesson in finding the scope of the modern sonnet, and using it to record the beauty, sadness, and complexity of the everyday.

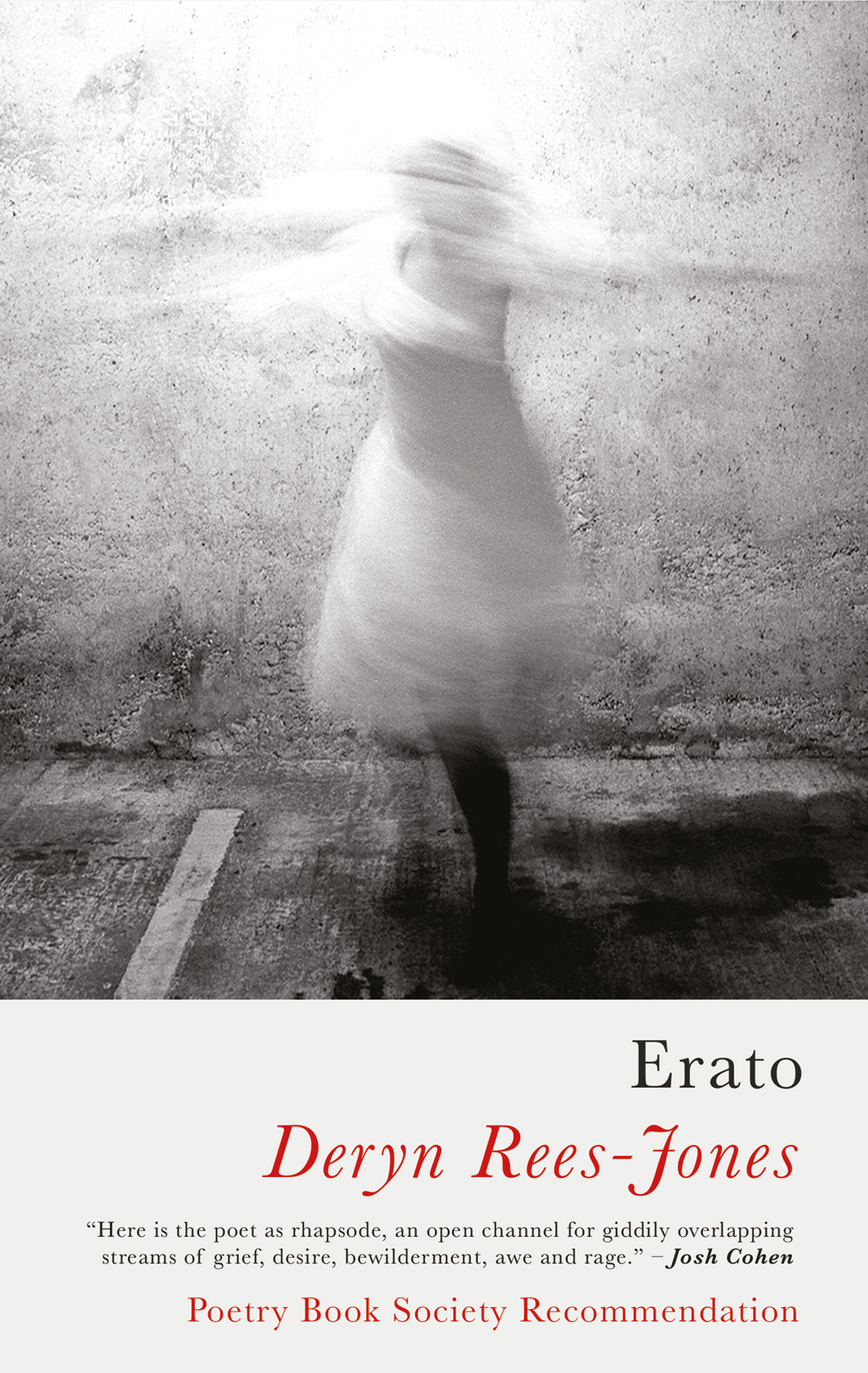

Deryn Rees-Jones – Erato

Perhaps the most difficult and surely the most demanding of the muses, Erato, who lends her name to Deryn Rees-Jones latest collection, insists that we ‘start now with the smallest things / a pile of blackened acorns, glinting beetle wings’. Sometimes painful, always honest, Erato is a brave book that offers no easy answers, but quietly continues the work of being, and the slow getting of wisdom.

Roger Robinson – A Portable Paradise

Roger Robinson’s characters bear witness to a country where ‘every second street name is a shout out to my captors’. Yet though Robinson is unstinting in his irony, he also gives us glimpses of something that his chosen protagonists also refuse to surrender – a taste, through the bitterness, of ‘life, of sweet, sweet life’.

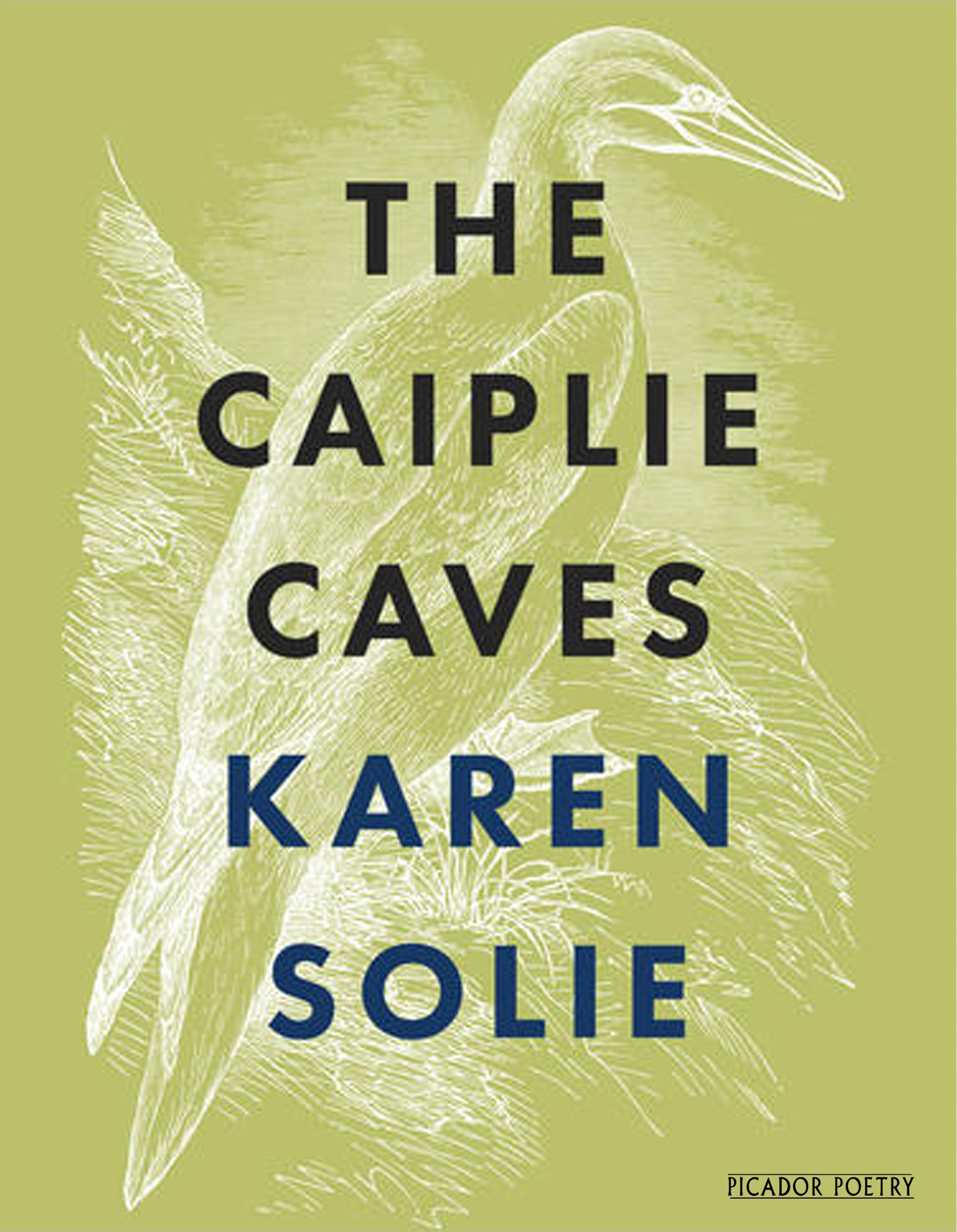

Karen Solie – The Caiplie Caves

‘Can a person be trusted whose principles forbid despair?’ Karen Solie asks. The answer is never in doubt but it is hard won – and its finding proposes a new question about the nature of trust and of hope that literally illuminates the darkness of our times as the old mystics lit up the darkness of the caves.

The winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2019 is Roger Robinson for A Portable Paradise.

This speech was given at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2019 Award Ceremony at the Wallace Collection, London, on 13 January 2020.

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘Roger Robinson’s characters bear witness to a country where ‘every second street name is a shout out to my captors’. Yet though Robinson is unstinting in his irony, he also gives us glimpses of something that his chosen protagonists also refuse to surrender – a taste, through the bitterness, of ‘life, of sweet, sweet life’.’ – John Burnside, Chair

T. S. Eliot Prize 2019: the Chair of judges’ speech by John Burnside

Anthony Anaxagorou – After the Formalities

If you are like me, you turn straight to the title poem in a collection, as I did with After the Formalities, to be drawn wholly and utterly into a poem of immense rhetorical and political power. Yet the book is full of such richness, with a wonderful tempered sense of history that comes of accommodating, but not ignoring, justifiable anger.

Fiona Benson – Vertigo & Ghost

When Fiona Benson gets after something, she does so with total commitment, like Kafka’s great trapeze artist, digging deep into the hurts and fears and tendresses that haunt us most, not because she is cruel, but because she knows that, if we are to live with monsters, we must pass through the place where they live and emerge, less innocent, but wiser, on the other side of fear.

Jay Bernard – Surge

In Surge, Bernard stands face to face with the full horror of the New Cross Fire, bringing a fierce sense of history and a powerful rhetorical gift to what could have been an overwhelming battle, transforming what might have been a howl of protest against many decades of racism and prejudice into an enduring testament to justice.

Paul Farley – The Mizzy

To open a collection by Paul Farley is a little like dipping into an illuminated manuscript from the rich Medieval era and yet it feels very local – local to specific places and times, local to a ‘certain patch of rocks between two sides’ and ‘the swing bridge at Preston Docks’ local to who, when and where we are, now, in our dreams and in our waking.

Ilya Kaminsky – Deaf Republic

Every now and then a new poetry appears that, even if it speaks your language, it nevertheless teaches us new terms, a new vocabulary. Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic is just such a poetry. Neither its pathos nor its cruelty are final – indeed nothing is, and if the question ‘What is a man?’ can be answered as ‘the quiet between two bombardments’ so the question ‘What is silence?’ can evoke the reply, ‘Something of the stars in us’.

Sharon Olds – Arias

By my count, Arias is Sharon Olds’s twelfth collection and in it we see a master poet at the full height of her powers. Who else would compare her speaker-self to ‘a seal sticking halfway out of the concave comber it is riding’? – and even exultant: as much celebration as elegy, even as, undeniably, it gives us some of the finest elegiac poems written in recent times.

Vidyan Ravinthiran – The Million-petalled Flower of Being Here

To commit an entire collection to the sonnet is a brave act. It shows not just trust in one’s abilities but also a humility before the form that any kind of success demands. Few have achieved this is many years but The Million-petalled Flower of Being Here offers an object lesson in finding the scope of the modern sonnet, and using it to record the beauty, sadness, and complexity of the everyday.

Deryn Rees-Jones – Erato

Perhaps the most difficult and surely the most demanding of the muses, Erato, who lends her name to Deryn Rees-Jones latest collection, insists that we ‘start now with the smallest things / a pile of blackened acorns, glinting beetle wings’. Sometimes painful, always honest, Erato is a brave book that offers no easy answers, but quietly continues the work of being, and the slow getting of wisdom.

Roger Robinson – A Portable Paradise

Roger Robinson’s characters bear witness to a country where ‘every second street name is a shout out to my captors’. Yet though Robinson is unstinting in his irony, he also gives us glimpses of something that his chosen protagonists also refuse to surrender – a taste, through the bitterness, of ‘life, of sweet, sweet life’.

Karen Solie – The Caiplie Caves

‘Can a person be trusted whose principles forbid despair?’ Karen Solie asks. The answer is never in doubt but it is hard won – and its finding proposes a new question about the nature of trust and of hope that literally illuminates the darkness of our times as the old mystics lit up the darkness of the caves.

The winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2019 is Roger Robinson for A Portable Paradise.

This speech was given at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2019 Award Ceremony at the Wallace Collection, London, on 13 January 2020.