The earliest surviving letter from T. S. Eliot was written in Gloucester, Massachusetts in June 1898. In the letter, addressed to his “Papa”, 9-year old Eliot writes of the coolness of the house in the morning, a broken microscope, butterfly and spider specimens, and hunting for birds with his sister, Charlotte. He was writing at the beginning of a three month summer holiday which his family would take each year, retreating from the St Louis heat to the cooler climes of New England where the ancestral roots of the Eliot family lie. From the age of four, Eliot and his family spent their summers in the small fishing town of Gloucester on the Cape Ann coast, about forty-miles north east of Boston. In their first few years there, the family stayed in the Hawthorne Inn on Wonson’s Point. The inn, named after writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, overlooked the shore and had its own landing for boats, and from here the family would have been planning their future summer home at Eastern Point, on land purchased by Eliot’s father in 1890.

The family took photographs of their summers and the photographs and accompanying captions tell us more about how the Eliots spent their days. They went on boat trips, bicycled, played on the beach, watched a swimming race, played golf, and met with friends and family. Sometimes Eliot would be surrounded by adults and at other times he played with his cousins and the children of other families staying in the area, including three year old Dorothy with whom he had his first ‘love affair’.

‘I had my first love affair at (as nearly as I can compute from confirmatory evidence) the age of five, with a young lady of three, at a seaside hotel. Her name was Dorothy: that is all I know. My feeling towards her was expressed entirely by bullying, teasing, and making her fetch and carry: yet I remember clearly that I pined for a bit after we were separated in the autumn.’

– T. S. Eliot to John Hayward, 1939

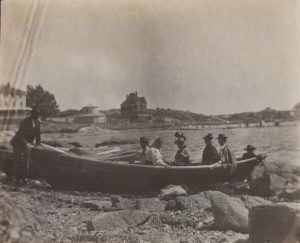

In the photograph below, Eliot (aged 6) can be seen in a wide-brimmed hat, tucked up in the stern of a boat, his mother and nanny, Annie Dunne, sat just in front of him, about to be pushed out to sea. This was, perhaps, one of Eliot’s earliest boat trips and sailing would become a favourite pastime of his in years to come.

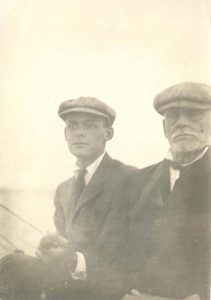

In another photograph taken that year, a relaxed looking Henry Ware Eliot has his arm around his son as they take a trip out on the Bickford’s boat.

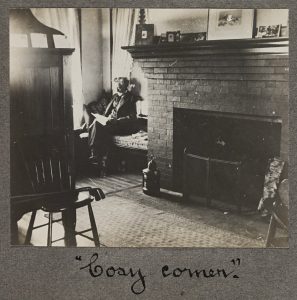

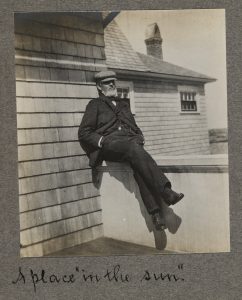

The house built by Eliot’s father, named ‘The Downs’, was completed in 1896. It is described in America as a ‘cottage’, but is a far cry from the small, low-ceilinged house you might expect to find in England. Spread over three floors, with a large verandah and covered in shingles, the house was spacious and airy with ‘a cosy corner’ and ‘a place “in the sun”’. It was built on the highest ground on Eastern point, south-east of the town – the first house to be built there – with unobstructed views down to the sea. One of the photographs from 1895 is taken from where the house now stands, with a miniscule Eliot standing on rocks in the distance; beyond him a sail boat can be seen out at sea. The caption reads ‘Site of house at E. Point before house was built. T.S.E. on rocks marks limit of lot’.

Eliot was known by some neighbours as ‘Little Tom’ and one of the locals remembered his keen interest in sea life, and sailing boats with her brother. In The Dry Salvages, Eliot recalled his discoveries of marine life as a child:

The starfish, the horseshoe crab, the whale’s backbone;

The pools where if offers to our curiosity

The more delicate algae and the sea anemone.

It tosses up our losses, the torn seine

The shattered lobsterpot, the broken oar

Gloucester is one of the earliest English settlements and was, and still is, a busy fishing port. As a boy Eliot could be found talking to Gloucester’s fishermen and sailors and enjoyed reading tales of seafaring adventures. Years later he would preface a book by one of those Gloucestermen, James B. Connolly. In his preface to Connolly’s Fishermen of the Banks (published by Faber & Gwyer in 1928), Eliot writes ‘There is no harder life, no more uncertain livelihood, and few more dangerous occupations… Gloucester has many widows, and no trip is without anxiety for those at home.’

Fare forward voyagers

And pray for those who were in ships, and

Ended their voyage on the sand, in the

sea’s lips

Or in the dark throat which will not reject

them

– The Dry Salvages

The fishermen’s stories, he writes could ‘be learnt by word of mouth from the men between trips, as they lounged at the corner of Main Street and Duncan Street in Gloucester’. As a boy, Eliot took delight in these stories which made their way into the draft of ‘Death by water’ in The Waste Land; four pages of text was eventually reduced to the last three stanzas. The draft tells the tale of a schooner which passes out past the Dry Salvages around the Cape, before getting into trouble after hitting ice, with fatal results.

We beat around the cape and laid our course

From the Dry Salvages to the eastern banks

…

Thereafter everything went wrong.

A water cask was opened, smelt of oil,

Another brackish.

Then the main gaffjaws

Jammed

– Draft of The Waste Land

Eliot and his brother, Henry, were taught to swim and sail by an old mariner nicknamed Skipper, and sailing featured heavily in his summers – from boyhood to his student days at Harvard. His friend, W. G. Tinckom-Fernandez recalled visiting Eliot at the summer house where he would take him sailing in his catboat, describing Eliot as being as good a sailor as any in Gloucester.

His own little boat, Elsa, can be seen in this photograph of Eliot taking his parents for a sail. In 1917, he wrote to his mother that he wished he could take her out sailing in Bosham, England where he was staying at the time, remembering with fondness their sailing in Gloucester: ‘I don’t regret all the sailing that you and I and father did together, I assure you!’.

The Dry Salvages are a group of rocks lying about a mile off the coast of Cape Ann and in Eliot’s day they were marked by a wooden tripod. In The Dry Salvages, Eliot describes the rocks that would have guided him and his fellow seamen out onto the open waters; they were the last seamark leaving and the first coming home.

And the ragged rock in the restless waters,

Waves wash over it, fog conceals it;

On a halcyon day it is merely a monument,

In navigable weather it is always a seamark

To lay a course by; but in the sombre season

Or the sudden fury, it is what it always was.

In that first letter to his father of 1898, Eliot mentioned hunting for birds – another of his favourite pastimes. Many years later, he reflected on the two different landscapes he grew up in and how he missed elements of nature from each place – in the case of Gloucester, ‘the small boy who was a devoted bird watcher never saw his birds of the season when they were making their nests’. In 1902, his mother gave him the Handbook of Birds of Eastern North America by Frank M. Chapman which Eliot described in a later inscription as ‘A much coveted birthday present on my 14th birthday’. In a letter to his friend, Bonamy Dobrée from 1932, he wrote that ‘The bird life of New England is the most wonderful in creation’. His 1935 poem, Cape Ann, is an ode to those ‘most wonderful’ birds.

O quick quick quick, quick hear the song-sparrow,

Swamp-sparrow, fox sparrow, vesper-sparrow

At dawn and dusk. Follow the dance

Of the goldfinch at noon. Leave to chance

The Blackburnian warbler, the shy one. Hail

With shrill whistle the note of the quail, the bob-white

In the spring of 1958 Eliot and his wife, Valerie, went to America where he gave lectures and poetry readings, and introduced Valerie to his family for the first time. While staying in Cambridge, Massachusetts, they took a day trip to Gloucester where Eliot spent a happy morning exploring Eastern Point and the former family home – the first time he’d been there since his twenties. Later that day at a lunch, Eliot was apparently delighted by the sight of purple finches and goldfinches feeding by the window – the keen birdwatcher of his childhood remained.