It worked in The Waste Land. But it made work in the British Museum nearly impossible for a young T. S. Eliot.

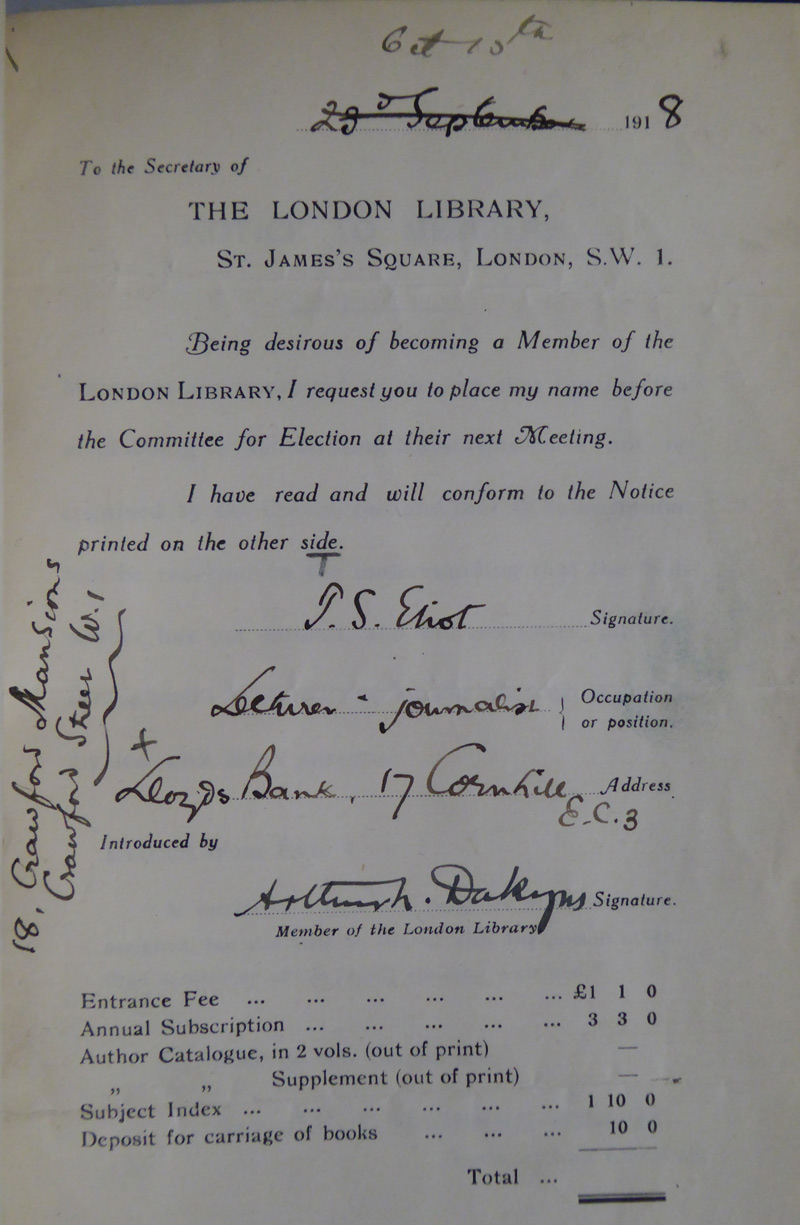

For no sooner had he settled at his desk each Saturday afternoon than, ‘there sounded the familiar warning’: ‘’Hurry up please, it’s time’. Employed at Lloyds bank, Eliot had only a few precious hours at the weekend for his writing. And by 1918, he’d had enough. So, like many great writers before him and since, T. S. Eliot joined the London Library. He would remain an active member for the rest of his life, serving as President from 1952 until his death in 1965 (during which time one Sir Winston Churchill served as Vice President under him).

It would prove to be an extremely productive place for Eliot down the years, and not just because of the lack of tannoy announcements. The London Library’s idiosyncratic shelving system – where ‘Insanity’ leads to ‘Inns of Court’ and ‘Football’ is followed by ‘Fools’ – was an unending source of delight for such a voracious, allusive and kaleidoscopic imagination as Eliot’s.

The air of productive calm (set off against the bustle of central London), combined with the ability to ‘take ten volumes home with me’ from the open shelving meant that for Eliot, ‘without the London Library, many of my early essays could never have been written’. Eliot recognised it as a place that fires the imagination and cultivates the soul, a place of curious books and even more curious people.

It was something he went out of his way to protect, donating handwritten manuscripts of The Waste Land to Library auctions and even appearing in court as a star witness when the library was under threat in the 1950s, despite troubles with his false teeth ‘which did not allow him to eat raspberries in public’. Eliot was unyielding: ‘the disappearance of the London Library would be a disaster to civilisation’, let alone his own writing.

So if, like T. S. Eliot you are thinking of joining the London Library, and following in the footsteps of the likes of Lord Alfred Tennyson, Virginia Woolf or Hannah Sullivan – much of whose T. S. Eliot prize-winning collection Three Poems was written in the library – then the message is clear: ‘Hurry up please, it’s time’.

Eliot’s joining form, dated October 1918

The London Library offers over one million books and periodicals dating from 1700 to the present day which are all available for borrowing. As a member you can browse 17 miles of open access shelves for an unforgettable voyage of literary discovery.