2005

T. S. Eliot Prize

Winner

The Chair of the judges’ speech

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘Poetry matters, and this generous prize is a sign of that. Why does it matter? Because it is an intrinsic answering-back against the bad language all around. The medium of poetry is words, and words are in currency all around for all manner of purposes not in the least poetic. Indeed for several purposes which poetry must body and soul implacably oppose.’ – David Constantine, Chair

T. S. Eliot Prize 2005: the Chair of judges’ speech by David Constantine

This year I and my fellow-judges, the poets Kate Clanchy and Jane Draycott, looked at 90 collections, from 28 publishers.

The Award, for which I would like to thank the Poetry Book Society, which awards the Prize, and Mrs Valerie Eliot, who gives the winner’s cheque for £10,000, is an encouragement to poetry and a sign that it matters. Poetry, the least commercial, the least spoilt of the arts, is largely its own reward. Nonetheless, the few prizes, the acts of recognition, are very welcome.

Judging – arriving at a long list, a shortlist, a winner – is a serious business. Also enjoyable, convivial, heartening, illuminating. But serious, for the judges, in this sense: we put our names to the lists, we stand by them. By making our choices we say publicly: we think these writers are a credit to poetry, we think their poems do what poems should do.

What should poetry do? Poetry should try to say what it is like being human here and now. If you read the poets on our list, and if you heard them read yesterday evening, you will agree, I hope, that they demonstrate how various are the ways in which poems may say what it is like. The locus of that enquiry may be very close to home, in the personal life, in the family, the immediate environment. But it is noticeable how many of the poems in these ten collections extend much further, over the globe in fact, even beyond the globe into our very unnerving dealings with the interstellar spaces. Also how many go abroad into other literatures and fetch into English things we see now that we cannot do without. And how they go back in time, into lives lived centuries ago, and again we are made to see that we cannot do without these revived connections with the past. Not one of these collections is in the least insular. All the writers here extend and enlarge our sympathies.

These poets are at various stages in their writing lives – they differ in how long they have been writing and publishing and how much success and recognition they have had. But they all – and in our reading we were on the look-out for this – have a good sense of what the English language has done already, what shapes, forms, rhythms, modes of feeling and technical strategies our colossally rich literature has at its disposal. That is very important. Every writer connects with, and the best actually alter, the total corpus of poetry to date, joining in and shifting all the inter-relations. So there are traditional forms here – rightly, since much of the stuff of poetry – love and death – is traditional because, in that sense, being human is traditional. But they are old forms understood and adapted to where we are now, to our real present circumstances, so connecting us with the general whilst insisting on particularity.

I haven’t named any names in these few notes, but I had names and indeed individual poems in mind all the way. So I was testing our choices against our idea of what poetry should do – and at every turn felt they were corroborated.

Poetry matters, and this generous prize is a sign of that. Why does it matter? Because it is an intrinsic answering-back against the bad language all around. The medium of poetry is words, and words are in currency all around for all manner of purposes not in the least poetic. Indeed for several purposes which poetry must body and soul implacably oppose. It is against lying, against evasion and shoddiness of speech. Against all the ways of speaking and writing which reduce our humanity, narrow our sympathies, wither our ability to think and feel. Against all the forces of cretinization. Poetry is an intrinsic fight-back against all that. These writers – intelligent, passionate, witty, inventive – prove it: poetry will help us into what Lawrence called ‘a new effort of attention’. And it hardly needs saying that without that effort, without continual new efforts of attention, we shall drift into some final showdown engineered by people whose speech and sensibilities are, to put it mildly, lacking in nuance.

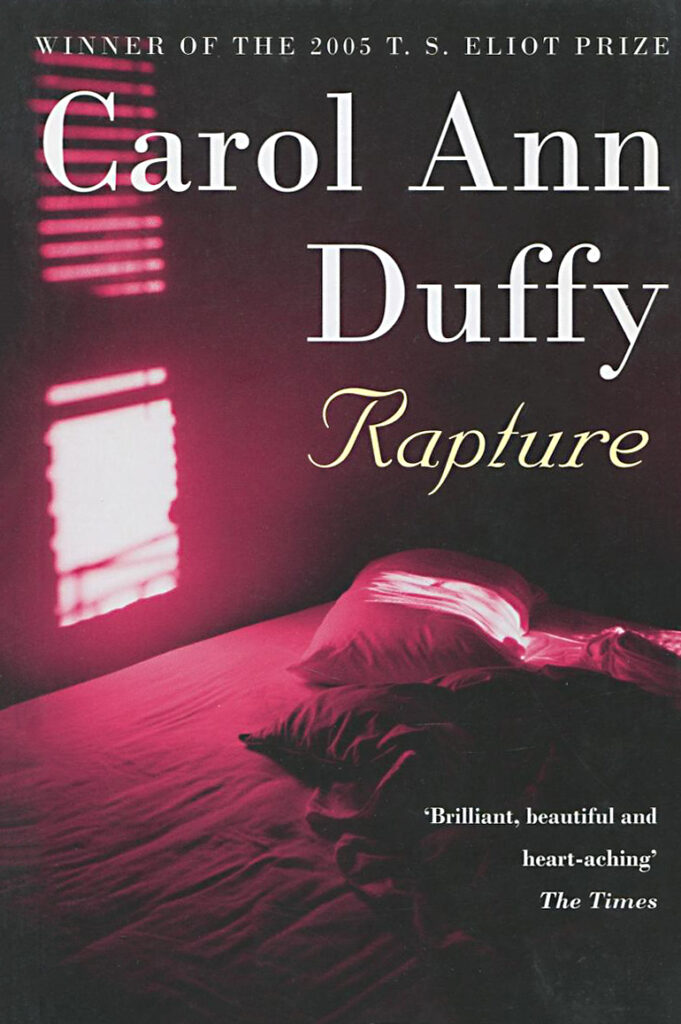

I repeat, we read 90 collections. We made a shortlist of ten. Every writer on that list is there because we thought very highly of his or her work. But in the end the Prize has to be awarded to one. We discussed it thoroughly, and concluded unanimously that this year’s T. S. Eliot Prize should be awarded for a collection that is coherent and passionate, very various in all its unity of purpose – and that in the language and circumstances of our real modernity, re-animates and continues a long tradition of the poetry of love and loss. That collection is Rapture by Carol Ann Duffy.

This speech was given at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2005 Award Ceremony, London, on 16 January 2006.

First published on the Poetry Book Society website.

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘Poetry matters, and this generous prize is a sign of that. Why does it matter? Because it is an intrinsic answering-back against the bad language all around. The medium of poetry is words, and words are in currency all around for all manner of purposes not in the least poetic. Indeed for several purposes which poetry must body and soul implacably oppose.’ – David Constantine, Chair

T. S. Eliot Prize 2005: the Chair of judges’ speech by David Constantine

This year I and my fellow-judges, the poets Kate Clanchy and Jane Draycott, looked at 90 collections, from 28 publishers.

The Award, for which I would like to thank the Poetry Book Society, which awards the Prize, and Mrs Valerie Eliot, who gives the winner’s cheque for £10,000, is an encouragement to poetry and a sign that it matters. Poetry, the least commercial, the least spoilt of the arts, is largely its own reward. Nonetheless, the few prizes, the acts of recognition, are very welcome.

Judging – arriving at a long list, a shortlist, a winner – is a serious business. Also enjoyable, convivial, heartening, illuminating. But serious, for the judges, in this sense: we put our names to the lists, we stand by them. By making our choices we say publicly: we think these writers are a credit to poetry, we think their poems do what poems should do.

What should poetry do? Poetry should try to say what it is like being human here and now. If you read the poets on our list, and if you heard them read yesterday evening, you will agree, I hope, that they demonstrate how various are the ways in which poems may say what it is like. The locus of that enquiry may be very close to home, in the personal life, in the family, the immediate environment. But it is noticeable how many of the poems in these ten collections extend much further, over the globe in fact, even beyond the globe into our very unnerving dealings with the interstellar spaces. Also how many go abroad into other literatures and fetch into English things we see now that we cannot do without. And how they go back in time, into lives lived centuries ago, and again we are made to see that we cannot do without these revived connections with the past. Not one of these collections is in the least insular. All the writers here extend and enlarge our sympathies.

These poets are at various stages in their writing lives – they differ in how long they have been writing and publishing and how much success and recognition they have had. But they all – and in our reading we were on the look-out for this – have a good sense of what the English language has done already, what shapes, forms, rhythms, modes of feeling and technical strategies our colossally rich literature has at its disposal. That is very important. Every writer connects with, and the best actually alter, the total corpus of poetry to date, joining in and shifting all the inter-relations. So there are traditional forms here – rightly, since much of the stuff of poetry – love and death – is traditional because, in that sense, being human is traditional. But they are old forms understood and adapted to where we are now, to our real present circumstances, so connecting us with the general whilst insisting on particularity.

I haven’t named any names in these few notes, but I had names and indeed individual poems in mind all the way. So I was testing our choices against our idea of what poetry should do – and at every turn felt they were corroborated.

Poetry matters, and this generous prize is a sign of that. Why does it matter? Because it is an intrinsic answering-back against the bad language all around. The medium of poetry is words, and words are in currency all around for all manner of purposes not in the least poetic. Indeed for several purposes which poetry must body and soul implacably oppose. It is against lying, against evasion and shoddiness of speech. Against all the ways of speaking and writing which reduce our humanity, narrow our sympathies, wither our ability to think and feel. Against all the forces of cretinization. Poetry is an intrinsic fight-back against all that. These writers – intelligent, passionate, witty, inventive – prove it: poetry will help us into what Lawrence called ‘a new effort of attention’. And it hardly needs saying that without that effort, without continual new efforts of attention, we shall drift into some final showdown engineered by people whose speech and sensibilities are, to put it mildly, lacking in nuance.

I repeat, we read 90 collections. We made a shortlist of ten. Every writer on that list is there because we thought very highly of his or her work. But in the end the Prize has to be awarded to one. We discussed it thoroughly, and concluded unanimously that this year’s T. S. Eliot Prize should be awarded for a collection that is coherent and passionate, very various in all its unity of purpose – and that in the language and circumstances of our real modernity, re-animates and continues a long tradition of the poetry of love and loss. That collection is Rapture by Carol Ann Duffy.

This speech was given at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2005 Award Ceremony, London, on 16 January 2006.

First published on the Poetry Book Society website.