‘This volume contains nothing new except a set of poems called ‘The Hollow Men’, which represents an even more advanced stage of the condition of demoralization already given expression in The Waste Land; the last of these poems — the disconnected thoughts of a man lying awake at night — consists merely of the barest statement of a melancholy self-analysis mixed with a fragment of the Lord’s Prayer and a morose parody of ‘Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush’. ‘This is the way the world ends’, the poet concludes, ‘Not with a bang but a whimper’.

No artist has felt more keenly than Mr Eliot the desperate condition of Europe since the War nor written about it more poignantly.’

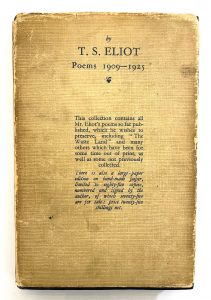

— Edmund Wilson’s review of Poems 1909-1925 (Faber, 1925).

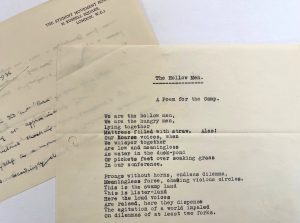

‘The Hollow Men’, composed in stages, was the first poem by T. S. Eliot to be published after The Waste Land had exploded onto the modernist scene in 1922. Unlike his other poems, ‘The Hollow Men’ had a public evolution and drafting process. The final five-part poem was published on 23 November 1925, but Parts I-IV were published in various combinations, across four international journals, ahead of the poem’s final form, during the winter of 1924-1925.

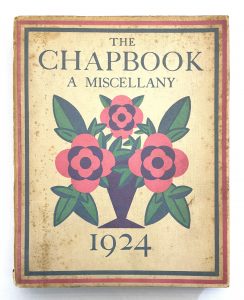

The first iteration of the poem was published in November 1924 as a three-part poem, ‘Doris’s Dream Songs’, in Harold Monro’s literary miscellany The Chapbook. Eliot appears to have been rather embarrassed by his offerings, suggesting Monro could take them or leave them…

I am sending you the only things that I have. Print them if you like or not, I dare say that they are bad enough to do the Chapbook no good and to bring me considerable discredit. If you want them you are welcome, if not, I am very sorry that I have done nothing better that I could give you. They were all written for another purpose and perhaps would not look quite so foolish in their proper context as they probably do by themselves.

— T. S. Eliot to Harold Monro, 5 October 1924

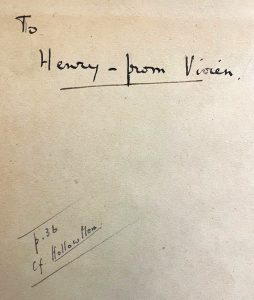

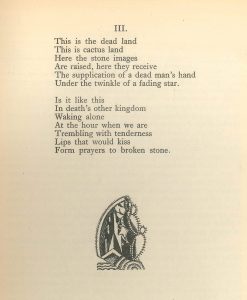

A copy of The Chapbook, which Vivien Eliot gave to Eliot’s brother, Henry, as a Christmas present in 1924, is now part of our collection. Below Vivien’s inscription, Henry (a keen collector of Eliotiana) has added his own note, ‘cf. The Hollow Men — compare with the final published poem of November 1925’. The poem is illustrated with a decoration by artist and designer E. McKnight Kauffer, showing us the ‘dead land […] cactus land’ ‘In death’s other kingdom’. Eliot would later separate ‘Doris’s Dream Songs’ into three: Parts I and II would become Minor Poems ‘Eyes that last I saw in tears’ and ‘The wind sprang up at four o’clock’; Part III would become the third part of ‘The Hollow Men’.

In a letter to his friend, Ottoline Morrell, Eliot gave a brief explanation of the poem and how it fitted into his current work:

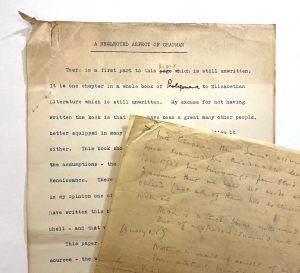

‘I am pleased you like the poems – they are part of a longer sequence which I am doing – I laid down the principles of it in a paper I read at Cambridge, on Chapman, Dostoevski and Dante – and which is a sort of avocation to a much more revolutionary style thing I am experimenting on.’

— T. S. Eliot to Ottoline Morrell, 30 November 1924

Eliot was referring to the poems published in The Chapbook. The longer sequence he mentions is ‘The Hollow Men’ and the ‘revolutionary thing’, Sweeney Agonistes. The paper that Eliot read to the Cam Literary Society was A Neglected Aspect of Chapman — the neglected aspect being shared commonalities between George Chapman, and Dostoevski (the modern) and Dante (the medieval).

Among the surviving manuscript and typescript drafts of ‘The Hollow Men’ is an early pencil draft of Part III (written on the back of a draft of ‘Eyes that last I saw in tears’ and ‘The wind sprang up at four o’clock’) now held in the Papers of the John Hayward Bequest of T. S. Eliot Material at King’s College, Cambridge. When endorsing the draft for Hayward some years later, Eliot noted two of his literary influences: William Morris’ The Hollow Land and Rudyard Kipling’s ‘The Broken Men’.

The second appearance of part (I) of the poem was published in November 1924 in Commerce, the French literary journal founded by Eliot’s cousin, Marguerite Caetani, earlier that year. Added to the head of the signed typescript Eliot sent to Caetani were strict instructions on adhering to the poem’s grammar: ‘Punctuation must not be altered TSE’.

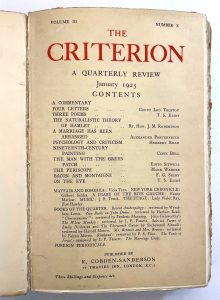

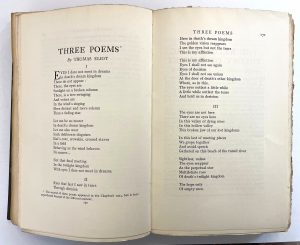

The next draft of the poem — what would become Part IV of ‘The Hollow Men’ — was published in the January 1925 number of Eliot’s own journal, The Criterion. ‘The eyes are not here…’ was printed as part of a group of ‘Three Poems’ under the authorship of ‘Thomas Eliot’. The group of poems included ‘Eyes that last I saw in tears’, published in The Chapbook the previous November.

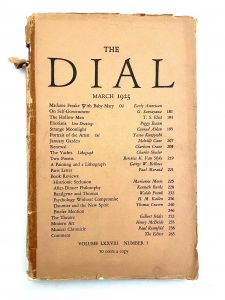

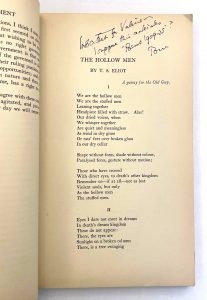

The fourth version of the poem appeared in The Dial, the American journal—run by Eliot’s schoolfriend and Harvard contemporary, Scofield Thayer—that first published The Waste Land in the United States. Eliot sent copies of Parts I, II III and IV of ‘The Hollow Men’ to Thayer in January 1925 and in March that year they were published as ‘The Hollow Men’ parts I-III. In his letter to Thayer, Eliot mentions a further part or parts he had yet to write: ‘here are the poems you have heard of and possibly a few more. There is at least another one in the series which is not yet written.’

Several months later, the poem was complete: a final Part V was added and revisions made to the other parts. It was published in Poems 1909-1925, and was, as Edmund Wilson pointed out, the only new poem in the volume published by Eliot’s new publisher and employer Faber & Gwyer.

Critical responses to ‘The Hollow Men’ gravitated towards the musical feel of the poem with Babette Deutsch describing ‘a new music’: ‘The religious craving, growing more insistent, introduces a purer lyricism.’ I. A. Richards, who thought the poem Eliot’s ‘most beautiful’, suggested his poetry could be labelled ‘a music of ideas’. What’s more, Richards believed, as did Eliot, ‘They are there to be responded to, not to be pondered or worked out’.

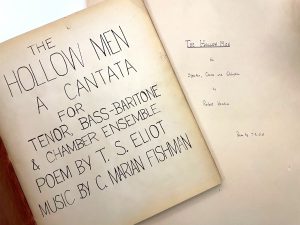

Eliot’s correspondence files reveal a steady flow of letters concerning the poem. Some of the letters came from composers wishing to set the poem to music. Two such unpublished musical scores, by Marian C. Fishburn and Hollywood music composer Robert I. Henkin, can be found in our collection. Eliot had a rule to refuse requests to authorise settings of ‘The Hollow Men’, but with Henkin’s appeal he made an exception. Eliot was ‘deeply touched’ by his letter and consented, ‘…as you have made this special appeal, I am not disposed to stand in the way of your having your setting performed’, adding ‘I must adhere to my general rule and say that it must not be published’. Henkin’s setting of ‘The Hollow Men’ was performed by a radio orchestra in Amersterdam. In his reply, Eliot also expressed his disagreement with those musicians who thought it adept for musical setting:

‘It is curious that one of the poems which has most attracted composers, should be The Hollow Men, which never seemed to me suitable for musical setting at all.’

— T. S. Eliot, 30 November 1956

Earlier that year Eliot had consented to John Pick’s request for a ballet to be called ‘The Hollow Men’, but as with setting the poem to music, he could not agree to the poem being recited alongside the ballet. The poem’s inherent musicality and suitability to dance adaptation has continued to inspire composers and choreographers, most recently with Kaija Saariaho’s 2022 piece, ‘Study for life’ performed at the Finnish National Opera and a dance composition by Ina Christel Johannessen performed at the Copenhagen Opera House in 2023.

The correspondence includes letters from school teachers and pupils, sharing their responses to Eliot’s work or querying the meaning of his poems and plays. One such letter (from 1963) is from an A‘Level class who are very upfront in stating that theirs is not a fan letter of ‘any sort’ and ‘more a letter of complaint’. The students were used to searching for ‘a symbolic meaning hidden in every word’ but ‘The Hollow Men’ had proved especially challenging in this respect. Why, they asked, did Eliot include the lines ‘Here we go round the prickly pear’, linking it with an old nursery rhyme? And were ‘The Hollow Men’ representative of current civilisation? Eliot’s answer, conveyed by his secretary, is succinct and non-elucidative: ‘Mr Eliot has asked me… to say that he does not believe in giving interpretations of his poetry; if readers of it have been moved at the time, that is all he asks.’

Some correspondents wished to share their responses to the poem, be they critical evaluations, or creative outputs. German Hans Combecher sent his attempt at a ‘bearable’ explanation of why Eliot’s poetry was so good and his interpretation of ‘The Hollow Men’, while Christopher Bunch at Hunter Liggett Military in Jolon, California, sent Eliot his screenplay script in the hopes of Eliot commenting on it (the screenplay was received two weeks before Eliot’s death so we shall never know his thoughts). Another creative output came from Mary Trevelyan and Eric Fenn while at a Student Christian Movement conference, with spoof poems of The Waste Land and ‘The Hollow Men’, performed by a student. Trevelyan sent the ‘shocking effort’ by herself and Fenn ‘as a mark of affection & esteem’. It was received with amusement by Eliot who thought the rendering might have helped his own delivery of the poem.

In 1946, Eliot discovered that his poem was the namesake for an undergraduate society at Cambridge when he was invited to dine with the ‘Hollow Men’, a group who met to read and study Eliot’s poetry. And how did the society members begin their meetings? Naturally, they opened proceedings ‘by chanting the refrain of your poem’. On learning of the existence of the society, Eliot hoped that the members would ‘eventually put on weight and find it necessary to adopt some more robust title’.

Chaplain and English school master, A. S. T. Fisher, sought Eliot’s opinion of his interpretation of the poem for a note he was writing to accompany the poem in a school’s anthology. School boys, wrote Fisher, had no respect for a poem they couldn’t understand, that couldn’t be explained: an explanation was necessary. Eliot gave perhaps his lengthiest reply to a query on the poem’s meaning. He agreed with Fisher’s assertion that he had the Styx in mind with the lines ‘Gathered on this beach of the tumid river’, ‘perhaps with a rather more antique than Dantesque association…’. Eliot was not making ‘political criticism’ but saw ‘no reason why the reader should not make that application’. Moreover, he ‘would not contest [Fisher’s] point about the influence of recent advances in psychology but if it is true the connection was unconscious and not deliberate.’ ‘Guy’ was the English, not American meaning and Eliot suggested it ‘worth while’ to point people to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

Eliot responded positively to actor Michael Redgrave’s letter asking how he should read the ‘Prickly-pear’ section of the poem:

‘The BBC have honoured me by asking me to read some of your poetry next Monday… which includes The Journey of the Magi and The Hollow Men… Rehearsing The Hollow Men, I am at a loss when I come to the “Prickly-pear’ verse… when I try to speak it I find that whatever tone of voice I adopt is unsuitable.’

Eliot replied:

‘the first and last quatrains should be spoken very rapidly, without punctuation in a flat monotonal voice, rather like children chanting a counting-out game. The intermediate part, on the other hand, should be spoken slowly although also without too much expression, but more like the recitation of a litany.’

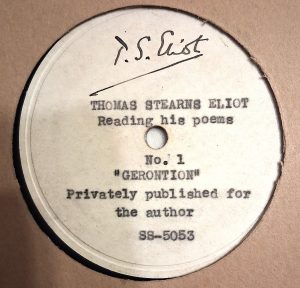

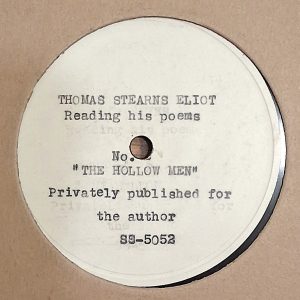

Eliot followed faithfully his own directions in a recording of the poem made at Harvard in 1933. A gramophone record containing Eliot’s reading of ‘The Hollow Men’ on one side and ‘Gerontion’ on the other was produced by Harvard and six copies sent to Eliot to distribute amongst a select group of his friends: Geoffrey Faber, Frank Morley, Virginia Woolf, Ottoline Morrell, Marguerite Caetani as well as Eliot himself (which we suspect was given to Alida Monro to whom he offered a copy). The record label, signed by Eliot, tells us that it was ‘Privately published for the author’.

Lines from the poem entered the English lexicon during Eliot’s lifetime and show no signs of leaving it. It has featured in film and television scripts, political speeches, Reddit threads, video games, countless articles, fiction and non-fiction. Perhaps the most famous appearance of the poem in popular culture is in a scene from Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 war epic, Apocalypse Now. At the film’s conclusion, we hear Colonel Walter E. Kurtz, played by Marlon Brando, reciting the poem shortly before his death.

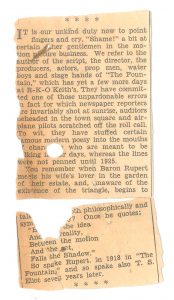

But this was not the first Hollywood film to feature the poem. ‘The Hollow Men’ entered popular culture as early as 1934, when a young Harvard graduate, Sherman Conrad, sent Eliot a press cutting about the poem’s improbable inclusion in Hollywood film, The Fountain. Lines from the poem (‘Between the idea / And the reality / Between the motion / And the act / Falls the shadow’) were spoken by one of the film’s main characters, Rupert, in 1918 – seven years before the poem’s publication. The note begins ‘It is our unkind duty to point fingers and cry, “Shame!” a bit at certain other gentlemen in the motion picture business. … TO wit they have stuffed certain famous modern poesy into the mouths of characters who are meant to be talking [in earlier] days, whereas the lines were not penned until 1925.’ Eliot was amused by the cutting, but thought that real fame ‘only comes when quotations are used in bill board advertisements: by that time one might as well be buried.’

The popular opinion, put forward by Edmund Wilson and others, was that ‘The Hollow Men’ was a reaction to the First World War, a voice for and of the masses. But it was not. A decade after the poem’s publication, Eliot shared ‘The Hollow Men’s’ auto-biographical roots:

‘incidentally, I have written one blasphemous poem, “The Hollow Men”: that is blasphemy because it is despair, it stands for the lowest point I ever reached in my sordid domestic affairs.’

— T. S. Eliot to his brother, 1 January 1936