During and shortly after the Second World War, T. S. Eliot was invited by the British Council to give lectures, poetry readings and open book exhibitions abroad. The visits were seen as a form of ‘cultural warfare’ at a time when much of Europe was at war. Although seven trips were planned between 1940 and 1951, only four came to fruition: the trips were fraught with planning difficulties with the logistics of travel, safety risks and the possibility of internment during the war.

The British Council (originally the British Committee for Relations with Other Countries) was established in 1934, at a time of global instability. The Council’s aims, as stated in their 1940/41 report, were:

‘to create in a country overseas a basis of friendly knowledge and understanding of the people of this country, of their philosophy and way of life, which will lead to a sympathetic appreciation of British foreign policy, whatever for the moment that policy may be and from whatever political conviction it may spring.’

Eliot’s involvement with the British Council began in 1940 with an invitation to give six lectures on English poetry at the British Institutes in Italy –from Palermo to Milan– over a fortnight in May the following year. At this stage of the war Italy was neutral, but by no means a safe destination. Eliot accepted the invitation and made plans to have a private audience with the Pope, hoping to break the journey back to Rome with a visit to Ezra Pound in Rapallo.

In the Spring of 1940 Eliot drafted two lectures for the tour. He had been asked to lecture on ‘Eng. Metaphysical or religious poetry, and a modern subject’. Eliot began his lecture on a modern subject, archivally titled ‘The Last Twenty-Five Years of English Poetry’, by looking at the changes in a living language as a means to understand how English poetry had developed in the previous twenty-five years: ‘A language that is not merely still spoken, but alive, is language that is changing. It changes first in current speech, which reflects, often in very indirect ways, the social, material and spiritual changes happening to the people who speak it.’ This discussion of an evolving language, perpetuated by the continuous change in the spoken language, would be picked up again by Eliot in ‘The Music of Poetry’ and ‘Poetry, Speech and Music’, a lecture written for a British Council tour of Sweden in 1942.

With growing concerns about safety, and just days before he was due to leave for Italy, Eliot sought advice from British diplomat Robert Vansittart. He was keen not to cancel the trip – it would make a bad impression on the Italians to pull out at the last minute – but was understandably wary: ‘One does not look forward with equanimity’ Eliot wrote ‘toward being interned on for the duration of the war’. Vansittart’s advice was not to go, but the British Council held off making a decision until the last minute, putting Eliot in a quandary, conflicted on what to do: ‘It seems to me rather tough that a private individual should have this responsibility put on him’ he wrote to John Hayward on 15th May. A phone call in which Vansittart repeated his advice ‘still more strongly’ lead to the trip being cancelled, the risk of Eliot getting stuck in Italy, with the Foreign Office unable to get him out, was too great. The decision couldn’t have been more pertinent – on the 10th June 1940, the day Eliot was to have returned to England, Italy declared war on France and Britain. The lectures Eliot had prepared would never be heard and would remain unpublished until their inclusion in Volume 6 of The Complete Prose of T. S. Eliot (2017).

In December 1941, Eliot was invited on a lecture tour scheduled for spring 1942, this time in neutral Sweden. He was invited by Ronald Bottrall, a Faber poet taken up by Eliot who had recently been stationed in Stockholm as the British Council’s representative. Bottrall was keen to get notable people over:

‘What I am particularly interested in is getting a few really important people across for short lecture tours in this country. The Swedes feel that they have been badly starved by England during the last eighteen months and it is vitally necessary that we should do something to offset the enormous pressure of Germany on this country’

Bottrall thought it would be best to send well-known figures over to Sweden and had had calls from Uppsala and Lund requesting Eliot in particular to come and speak. Eliot would provide ‘double-value’ owing to his former American citizenship, since America had just joined the war. Eliot was sceptical about the value of the evangelical work a British Council lecture tour would bring but thought, on balance, that the trip would do enough good to warrant the obvious side effect of disturbing his other duties and activities. Again, Eliot sought guidance from Lord Vanisttart, and art historian Kenneth Clark who was about to set off on his own British Council tour of Sweden. Neither man spoke encouragingly: ‘Clark also is of the opinion that this kind of propaganda is foolish and degrading; Vansittart… thinks it a waste of time, but advises going: it is just one of the things that we have to do because the Germans do it…’

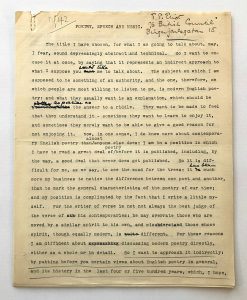

At the end of March Eliot took a week off to write two lectures for the Swedes: ‘Poetry in the Theatre’ and ‘Poetry, Speech and Music’ (having rejected Ronald Bottrall’s suggestion that he should talk about Christian Society). Neither speech was published, though ‘Poetry, Speech and Music’ bore many similarities to ‘The Music of Poetry’ – a lecture delivered at the University of Glasgow in February 1942 and published in August that year. A typescript of ‘Poetry, Speech and Music’ annotated with Eliot’s handwritten revisions and marked with the address of the British Council in Stockholm, is preserved in our archives and was published for the first time in The Complete Prose of T. S. Eliot. It’s possible that Eliot read from this document or had it typed up with his corrections by a typist in Sweden.

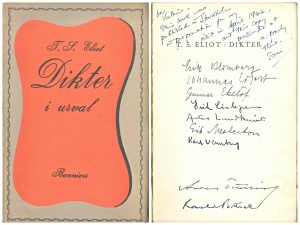

This time everything went ahead and the tour proved to be a great success. Eliot lectured In Stockholm, Uppsala, Lund and Gothenburg, as well as giving a number of poetry readings. To coincide with the tour, Bottrall had organised the publication of a selection of Eliot’s poems in Swedish translation, Dikter, which was well reviewed and contributed to the success of the trip. Eliot was given a copy of the book, inscribed by all but one of the translators. On his return to England, Eliot wrote to his brother, describing the Swedes as ‘very friendly and sympathetic… [and] rather touching’. He remained unsure of the visit’s benefits, but accepted his part: ‘What is accomplished by this sort of cultural warfare is impossible to say: but it [is] a part of total warfare which one must, as an individual, accept one’s part in’.

Following the tour, Eliot was invited to address Sweden on the subject of war poetry, broadcast on the BBC Swedish service on 24 July. Eliot’s text, which formed the basis for the broadcast, was published later that year in the journal Common Sense. The 1942 tour of Sweden had been part of the national ‘cultural warfare’ but it also played a part in Eliot’s own work. By the end of the year he had begun working on an essay influenced by his visit: ‘I am struggling to do a first draft of a long essay on the Definition of Culture – put into my mind, I think, by my visit to Sweden and consequent reflections on this curious new phenomenon of Export Culture, and the general tendency for politics to absorb culture.’ (letter to I. A. Richards, December 1942). The essay would become Notes Towards the Definition of Culture, published in four parts in New English Weekly, January-February 1943.

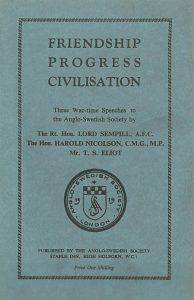

1943 was a busy year for T. S. Eliot and British cultural relations. On 18 March 1943, Eliot delivered a speech at an Anglo-Swedish Society luncheon entitled ‘Civilisation: The Nature of Cultural Relations’. In his speech – published in Friendship Progress Civilisation – Eliot reflected on his visit to Sweden the previous year: ‘does it not strike one as odd that it should require a war to stimulate the purely cultural relations between this country and a friendly neutral with which we have close ties of geography, race and civilisation? What about times of peace?’.

As well as overseas trips, the British Council engaged Eliot in talks at home. In April he travelled to Edinburgh at the invitation of Edwin Muir to address the French and Czechoslovakian Institutes on ‘The Social Function of Poetry’ – a speech he had delivered earlier in the month at the British-Norwegian Institute in London. At the same time, Eliot was exchanging letters with another representative of the British Council about a proposed visit to Iceland to open a book exhibition in the summer, a trip that had been postponed from the previous autumn due to Eliot’s ill health. Plans for the trip were laden with difficulties – there was no hope of Eliot getting a place on an American aeroplane which meant a lengthy voyage by sea: a one-week trip had become a three-week trip. Eliot was preoccupied, not only with writing his address, but with what sort of clothing he should take. He was particularly anxious about clothes in the context of war: ‘if I am torpedoed and happen to be rescued I don’t suppose there is the slightest hope of the British Council getting me any coupons to replenish my wardrobe.’ In mid-May, to Eliot’s relief, the trip was abandoned and a visit to Iceland never made.

Fast forward to December 1943 and Eliot was again invited to travel under the auspices of the British Council, this time to Algiers and Morocco in the spring or summer of 1944 to give lectures and poetry readings to the French émigrés living there. He was asked to present three lectures: on ‘The Social Functions of Poetry’, the influence of the French symbolist poets on English poetry (Eliot’s own idea), and an introduction to modern English poetry. The first and last lectures would be drawing on his 1942 Swedish lectures and the address he gave to the Norwegian Institute in 1943. Leading up to the proposed visit Eliot sought advice about ‘social behaviour in the tangle of personalities and parties which appear to be assembled there’. Increased restrictions on travel meant that the British Council was unable to get an exit visa for Eliot and the trip was postponed to the autumn. By then Eliot had put a great deal of time into his lectures and had ‘been measured for a tropical suit and shorts and a Bombay Bowler’.

With further time to plan the North African trip, the British Council proposed several additional destinations, extending the tour to Egypt, Cyprus and Malta. Eliot was prepared to be away for six weeks but not the three months proposed by the British Council. As time wore on Eliot was advised that the trip was becoming less useful – Lord Vansittart’s opinion this time was that a visit would no longer be of any use and that a trip to Paris would prove more helpful when it was possible to travel there. The plans did eventually move to Paris, with Eliot giving a talk there as part of the British Council’s Series Megret in May 1945.

In amongst requests to lecture, Eliot was also asked to provide references for acquaintances seeking employment with the British Council – he supported applications from John Betjeman, Stuart Gilbert and George Barker.

Invitations to lecture lessened as the war ended, and Eliot declined several trips in the late 1940s and 1950s, wanting to concentrate on work he had put aside during the war. His last lecture tour with the British Council was to Rome in December 1947, organised again by Ronald Bottrall who suggested he repeat his Stockholm lectures. The trip was made via Amsterdam where the British Council gave Eliot ‘a wonderful dinner of a dozen oysters, a prodigious beefsteak, and more fried potatoes that I had ever seen at once’. In Rome he lectured on ‘Poetry in the Theatre’ and ‘Poe and his Influence on European Literature’, gave a poetry reading and finally managed to meet Pope Pius XII– ‘the Pope made a very good impression on me; in fact I thought he compared very favourably with our dear Archbishop and is less like a Headmaster…’

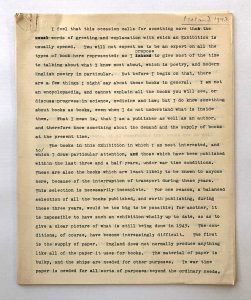

Having declined lecture tours in Czechoslovakia and Greece, Eliot’s last trip for the British Council was to open an exhibition of English books and manuscripts – Le Livre Anglais – at the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, in November 1951. In his speech, Eliot paid tribute to the bibliographer and, in doing so, he paid tribute to his friend, John Hayward, who was on the exhibition committee. A section of the exhibition devoted to material from the end of the 19th century to the present day, included a signed typescript of The Waste Land typed by Eliot between 1921 and 1922, an autograph manuscript of Ash Wednesday, and a rare copy of an acting edition of Murder in the Cathedral.

In a letter to Philip Mairet, Editor of New English Weekly, Eliot summed up his experience of touring with the British Council following his trip to Rome:

‘I feel like Sherlock Holmes, who summarised his history since last seeing Watson by saying “I then passed through Persia, looked in at Mecca, and paid a short but interesting visit to the Khalifa at Khartoum, the results of which I have communicated to the Foreign Office”.’

The Complete Prose of T. S. Eliot, vols. 1-7 is published online by John Hopkins Press and is available by individual and institutional subscription here.