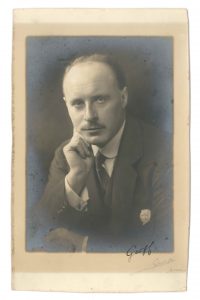

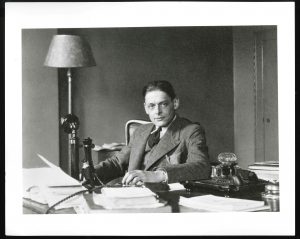

2025 marks one hundred years since T. S. Eliot began his career in publishing. On 23rd April 1925, Eliot was invited to join the newly formed publishing house of Faber & Gwyer as one of its Directors by the firm’s Chairman, Geoffrey Faber.

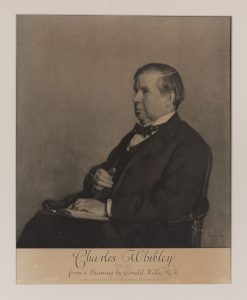

It all began with an introduction from Eliot’s friend and Criterion contributor, Charles Whibley, in the autumn of 1924. Whibley, a journalist, author, and editor, had ‘warmly recommended’ Eliot to Geoffrey Faber who was then running the small Scientific Press which specialised in publishing medical books and the highly successful weekly paper, The Nursing Mirror. The Scientific Press was in the process of diversifying the business, and listed on Geoffrey Faber’s memorandum of proposed ideas for the firm was the addition of a literary magazine to publish. The Criterion and its editor, with his literary connections and business experience from the world of banking, were just what he was after.

Faber and Eliot’s first meeting took place at Faber’s London home on the 1st December 1924. That evening, Faber noted in his diary that they had ‘had a long and interesting talk about The Criterion’. Eliot recalled their first meeting some thirty-five years later at the memorial service for Faber:

‘For personal reasons, I had found it necessary to change my means of livelihood, and to seek a new position which should also give some assurance of permanence. Faber, on the other hand, was looking only for a writer with some reputation among the young, who could attract the promising authors of the younger generation as well as of our own … He wanted an informal adviser and, in fact, a “talent scout”. My name had been suggested to him with warm commendation by my elder friend Charles Whibley, on an occasion when Whibley was a weekend guest at All Souls. I do not remember how it was, during the evening’s conversation between Faber and myself, that our two designs became identical. I suspect that it was merely that we took to each other.’

Valerie Eliot made a home recording of Eliot reading his memorial address – an extract from the recording is made available for the first time below.

At the time of this first meeting, Eliot was working in the Foreign & Colonial Department of Lloyds Bank where he’d been employed for the past seven years; his evenings were spent running and editing The Criterion, the journal he had founded with patron Lady Lilian Rothermere in 1922. He was finding it increasingly difficult to do both jobs – the latter without pay – and support his wife, Vivienne, who was in continuing poor health. ‘Few people realise what it means to have to put a whole days work into an evening’, he wrote to fellow editor and poet Harold Monro. And to his brother, Henry: ‘I was a damned fool ever to agree to run the review without a salary; or in fact to run it at all’. Eliot had been trying for months to find a way out of his job at the bank, where he had recently been made Head of his department, ‘which has meant much more responsibility and worry’. In a letter to his mother, he wrote of being ‘tormented and torn with indecision’ over his future. Eliot’s desire was to have enough financial independence to enable him to leave the bank. He was waiting to hear whether Lord Rothermere might have something to offer him, and was trying to hatch a plan to secure a private income but had little confidence in his own investing abilities. Aware of his friend’s need for change, Charles Whibley had suggested potential work for Eliot at the University of London, with Eliot writing that he ‘should be overjoyed if anything came of it’. He turned to his brother, Henry, who had more of a talent for investing. The owner of The Criterion, Lady Rothermere, had offered Eliot a salary of £300 a year on his leaving the bank and Henry worked out a salary for Eliot based on this £300 plus the US securities he managed for his brother. Whether it was the fact that Lady Rothermere was only willing to pay him when he left the bank – ‘If I am worth a salary, I am worth a salary whether I am in the bank or out of it’ – or he thought it too risky to leave, Eliot did not act on Henry’s proposal.

Eliot’s first meeting with Geoffrey Faber must have been tantalising: the prospect of an out for Eliot and a means to keep The Criterion going on much better terms.

A second meeting between Faber and Eliot followed, where in-depth discussions were had about how exactly things might work with The Criterion, which they proposed to change from a quarterly to a monthly. Faber’s memorandum of the meeting, to share with his fellow directors, remains in Eliot’s files. In the memorandum we see the detail of how the new arrangements could work, that Eliot thought he could get a circulation of 10,000 in two to three years (!) – by March 1925 this had become a more realistic ‘5000 within five years‘ – and Faber’s own opinion of The Criterion – ‘I hinted that the review was rather too high-brow, even too precious, for my tastes’. Faber was keen on Eliot’s contributions but thought them too few, with Eliot confessing the need to keep various literary groups on side: ‘Mr Eliot explained that he had had great obstacles to overcome in the way of placating various literary groups, by including their contributions in the quarterly, groups who would otherwise have been definitely hostile to him.’

The political leanings of the journal were also considered, ‘We agreed that it would be a mistake to give the review too definitely a Tory colour, and that the unique character of the paper was to be achieved, not by associating it with a political party or particular set of principles, but by collecting a team of sincere and able writers working together, under the stimulus of the editor’s personality, and stimulated by the type of criticism exhibited in the review columns of the paper.’

The idea to change The Criterion from a quarterly to a monthly journal reverted back, ‘The market is glutted with them’ (GCF, 9 March 1925). Faber’s idea for a quarterly was one that would rival the Quarterly Review and Edinburgh Review with room for more creative, imaginative contents; ‘fresh’ and ‘new’ art must be given a place. One of Faber’s chief criticisms of The Criterion was that the more interesting, creative items were too short, and the more difficult, obscure items were too long.

The two continued to thrash out a plan for The Criterion and how it, and Eliot’s existing literary connections, would complement and assist the publishing business. Eliot had initially suggested a rigid method by which the types of authors and subjects considered for the journal would also be considered for books. Faber, however, thought it unwise to restrict the business in such a way. He ‘tentatively’ suggested ‘that, if we entered into an alliance for the publication of a quarterly magazine or review, you might join us as a director, would go a long way towards establishing the kind of organic connection between the paper and the books which I should hope to see grow up.’ Faber’s primary focus in publishing The Criterion was to foster young talent which the publishing side would benefit from: ‘I should want to use the Review first and foremost as a stimulus to young writers, so that having helped them to find their souls in print we should have a succession of the right sort to go on from the writing of articles and stories to the writing of books’, somewhat mimicking what John Lane had done with the Yellow Book. Eliot thought it ‘only desirable to avoid any gross inconsistency etc. by publishing a book by some writer who had been consistently and steadily damned in the review.’ Subsequently practical matters on the physical production of the journal, subscriptions, spending on contributors and such were discussed.

With Faber wishing to bring Eliot onto the Board of Directors, there followed the need for testimonials to convince the other board members that they should take on, as Eliot himself put it, ‘a man of letters so obscure’ as he. One of these testimonials came from Charles Whibley whose verbal ‘warm commendation’ was consolidated by an equally warm written testimonial: ‘As a critic, he is the best and most learned of his generation and is respected (and a little feared) by the young. …I have a perfect belief in his star. He knows all the young writers and is well able to discriminate among them.’ Author Hugh Walpole was added to Faber’s memorandum to his fellow Board of Directors: ‘Mr Eliot is by far the most important figure as an influence in contemporary literature now in England. …In spite of his very high personal critical standards he has a wide appreciation of the different tastes of our English reading public and he has that finest editorial gift of all, the power to extract the highest standard of work from his contributors because of the force of his own personality.’

On 6th April 1925, Eliot was appointed as the Editor of a new quarterly journal to be published by Faber & Gwyer; later that month he was appointed a Director of the business. His salary would be £325 a year as Editor with an additional £150 as Director, paid half-yearly. Although he wouldn’t resign until November, Eliot had found a way out of the bank, and a new career in publishing.

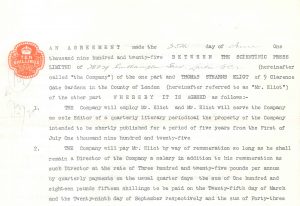

Eliot’s agreement with The Scientific Press – soon to be renamed Faber & Gwyer – included an important stipulation:

‘Mr Eliot agrees in the first instance to offer to the company for publication in book form by them upon terms not less favourable than those offered by any other publisher all or any original works written by him’.

From now on Eliot was a Faber Director and a Faber author.

Over the next few months Eliot approached a number of writers – many of them Criterion contributors – inviting them to consider publishing their next book with the new firm he was associated with. He suggested to Faber that Ada Leverson might have a book she could offer them on Oscar Wilde, he wrote to Orlo Williams that he would love to place Williams’ book before Faber & Gwyer, and at the end of the year he responded to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s gift of an inscribed copy of The Great Gatsby with an invitation for Fitzgerald to consider Faber & Gwyer as publishers of Gatsby in England (alas Fitzgerald had already promised it to Chatto & Windus). A series on foreign writers, or the Foreign Men of Letters series, was proposed and Eliot sought potential contributions from Richard Aldington, Bonamy Dobrée and Herbert Read. Read was a leading contributor for The Criterion and Eliot brought him onto the Faber list with two books: Poems 1919-1925 and Reason and Romanticism. Geoffrey Faber was already seeing glimpses of the promise of Eliot’s ‘star’ and how his position in the firm would see their reputation blossom. In a letter to co-owner Mrs Gwyer in October 1925, he wrote ‘One or two other things are also coming to us through him – not money-makers but reputation makers’.

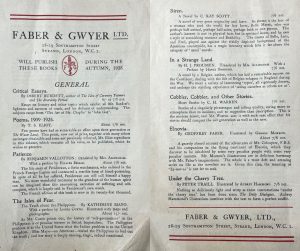

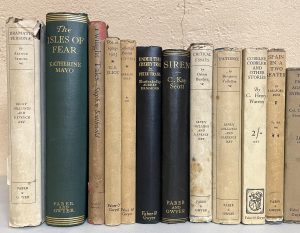

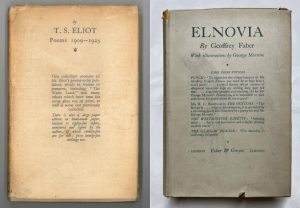

Alongside essays, children’s books and a series of health books – including the ever-prescient titles The Fight Against Infection and The Health of Children at School – Faber & Gwyer’s autumn 1925 announcements featured books by not one, but two of the firm’s directors. Geoffrey Faber’s ‘gravely absurd’ illustrated novel Elnovia, and Eliot’s Poems 1909-1925 featuring ‘all his verse, so far published, which he wishes to preserve’ were published at the end of the year. A limited edition of Eliot’s Poems, signed by the author, followed in January, selling out before publication.

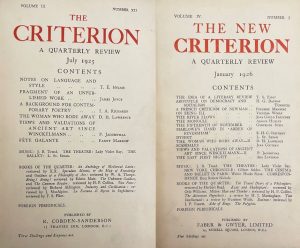

While the first Faber & Gwyer books were finding their way into readers hands, Eliot was working hard on preparing the first issue of The New Criterion. In his introductory essay for the first number, Eliot set out his thoughts on the purpose and function of the literary journal in The Idea of a Literary Review. Eliot thought that ‘the ideal literary review will depend upon a nice adjustment between editor, collaborators and occasional contributors’. Echoing Geoffrey Faber’s thoughts from their early discussions, Eliot suggested this adjustment should issue a ‘tendency’ rather than a ‘programme’, for a ‘programme is a fragile thing, the more dogmatic the more fragile. An editor or a collaborator may change his mind; internal discord breaks out; and there is an end to the programme or to the group. But a tendency will endure, unless editor and collaborators change not only their minds but their personalities.’

Contributors to the first issue of the The New Criterion included Virginia Woolf, Gertude Stein, D. H. Lawrence, Aldous Huxley, and John Gould Fletcher who would go on to publish his poetry with Faber & Gwyer. Geoffrey Faber’s wish for an ‘organic connection between the paper and the books’ he wished to see grow up on the Faber list, came to fruition. Three of Faber’s most notable poets from Eliot’s time – W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender and Louis MacNeice – all featured in the Criterion before making their way on to the Faber list, and, alongside their editor and mentor, all three continue to be published by Faber & Faber today.

While The Criterion came to an end in January 1939, Eliot remained a director at Faber until his death. He contributed to the publication of books from a variety of different genres, but his main role was as the firm’s poetry editor. In the early 1950s, he addressed a new generation of publishers on ‘The Publishing of Poetry’. Amongst the ‘selection of the small fruit’ of his experience that Eliot wished to impart to the Society of Young Publishers was this:

‘I think that for publishing poetry two conditions are necessary.

The first is, that the director or directors of policy in a firm publishing general literature must be convinced that English poetry has been one of the glories, perhaps the chief glory, of our literature in the past; and that, in consequence, it is a responsibility towards society that such a firm should do something for English poetry, by publishing the best poetry, written in our time, that it can get hold of. And the second essential is, that there should be somebody in the firm who can give a good deal of time to this department; someone, preferably, with a flair for recognising at an early stage poets who will be publicly recognised in ten or fifteen years’ time.’

At Faber, the first condition was satisfied by Geoffrey Faber and the team of directors he built around him; the second condition was met by the firm’s first poetry editor, T. S. Eliot, whose contribution to poetry as both poet and publisher continues to influence the publishing of poetry today.

With thanks to the Faber Archive.

Further reading: The Letters of T. S. Eliot: Volume 2 (1923-1925) and Toby Faber’s Faber & Faber: the Untold Story (2019).