Fiona Benson

‘Sometimes stories seem to fall in from another world, and writing the poem is just a way of listening to them’, says Fiona Benson, whose Ephemeron (Cape Poetry, 2022) is shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2022. We asked Fiona about stories and other worlds

T. S. Eliot Prize: Was entomological terminology an especially pleasurable part of the University of Exeter’s Project Urgency commission? You turn up some very nice words in your book – crypsis, instar, imago, exuvia….

Fiona Benson: Yes! The commission from Exeter was very broad, and allowed me to hone in on insects, which was a subject I was already very attracted to. I adore all the poems that exist about our ‘alpha’ fauna, the mammals – like Seamus Heaney’s badger, or Jen Hadfield’s hedgehog, or Norman MacCaig’s toad, but actually we interact with that kind of fauna once in a blue moon. On the other hand we are surrounded by insects, and know so little about their complex lifecycles and worlds. I loved meeting entmologists and diving into those deep wells of arcane knowledge about individual insects – and yes, the vocabulary of it is intensely pleasurable, and so apt. Exuvia for example just sounds exactly like what it describes. The whole experience was very inspiring.

TSEP: The switching between repulsion, attraction and identification in Insect Love Songs seems to announce the key themes in the book. It’s there in the Pasiphaë section too, in your poem ‘Daedalus’: ‘All craft leads back to nature, / its teeming innovation.’

FB: Yes I think so. I felt that the more I learned about certain insects the less I was freaked out by them – could even take them in my hands and empathise with their drives and vulnerability.

In a much broader sense, humans are often afraid of unknown behaviours. Me too, of course. A long time ago, I worked in an elderly mentally ill unit, and at first I found some of the people I cared for unnerving and strange, until the familiarity of caring for their bodies and developing a relationship with them broke those mental barriers down. When I imagined Asterios/‘the minotaur’ in the context of a society that exposed disabled children to die, I tried in the poems to look through different lenses – the way fearful strangers see him, the way his family see him. Fear is a very distorting lens. I think if we can recognise this, and work through it towards understanding and compassion, the world would be a better place.

TSEP: ‘You think of yourself locked-in, pre-teen’ says the speaker in ‘Leaf Insect’, comparing herself to ‘An insect that has learnt so deeply / to be leaf it almost forgets it can walk’. But many of the insects in Ephemeron do switch form. I really like Wiki’s definition of metamorphosis as ‘a conspicuous and relatively abrupt change in the animal’s body structure’. The changes of state seem to be part of your fascination for them. Is change (abrupt, conspicuous) available to the humans in Ephemeron? Perhaps for the teacher in your poem ‘Ink’?

FB: I’m not sure. All I know is that I am really fascinated by metamorphosis – in folklore and myth, in insect lives. Maybe it’s a metaphor for the imagination. I’d love to be a shapeshifter but am not (hence locked in!) The insects certainly switch form, but they can’t switch back…

TSEP: I listened to the excellent discussion you had with Emily Berry in a 2018 Poetry Review podcast about taboos and risk. ‘We should try to be as brave as our poems’, you say. Is the bravery in Ephemeron to do with facing terror?

FB: A question that’s been coming up lately has been how I keep myself safe when writing some of these poems, and it took me aback at first. What I’ve realised is, that it’s the poems themselves that keep me safe. The danger isn’t in the poems, it’s outside them in the world. Terrible things happen out there. Some of my poems bear witness to that terror, as you call it, and in that way dissent. I hope.

TSEP: You also talked about writing to find the poem, for the poem to emerge, to find out what poem is there. How did that happen with this book, perhaps in comparison with others?

FB: I wrote the insect poems first, and had a surprising amount of faith back then (since lost!) that if I immersed myself in research and followed all the interesting avenues of insect behaviour, then what would happen in the end would be a poem, and luckily poems arrived.

I didn’t intend to write about Pasiphaë at all; in fact, I’d sworn off Greek myth completely. But I taught a course using Cretan myth to inspire poetry, and doodling about in the writing exercises alongside my students, Pasiphaë arrived loud and clear, talking very explicitly about desire, and then with grief about her son. And that series fell out as I researched her story more. Sometimes stories seem to fall in from another world, and writing the poem is just a way of listening to them.

The boarding school poems I didn’t really want to write at all. I almost always preface these poems with the fact that I come from an RAF background, and had been to four or five state schools in different places (including Denmark) before the age of ten. I wore every colour of gingham summer dress, folks. I say this because I am embarrassed to have gone to boarding school, because it is so deeply associated with privilege. Anyway I have spent too long not writing about my childhood and eventually poems will burst out anyway. Which I guess is what happened with the motherhood poems too. Deep in the Republic of Motherhood, you write motherhood.

TSEP: ‘This tale you make us tell again and again’ (‘Queen’s Women: Daedalus and Icarus’). Why do we keep turning to Greek myths when they are so (truly) horrible? Do they inspire pity (only so useful) or fearlessness?

FB: I always have so many questions about Greek myths, usually about the women, who are often skipped over, or the so-called monsters. I think what myths do is leave a lot of gaps for the imagination to run riot in, and to explore contemporary concerns from a slant perhaps.

TSEP: In her maternal munificence ‘Mama Cockroach’ is very lovable and motherly love is also powerfully described in ‘Edelweiss’: ‘how mothers move in the dark like shining wounds, / like gaps in being. She sang, and all the hurt / and beautiful universe, all the souls / came crowding in.’ Though a cockroach is never safe, does a mother ‘somehow coalesce in your last firing cells […] tell you / how deeply you are loved’ (‘Dispatches’)?

FB: This is a very tender question. I think most of us as parents want to comfort our children, who will always be our children, in their hours of darkness. And the thought that we might not be able to is very frightening.

TSEP: Ephemeron deals with many terrors but there is often a glimmering light, a chance phosphorescence. Of course, light’s everywhere in the book – in the several firefly poems, the ‘lit fuse’ in ‘Field Crickets’. Is this unlooked-for light a sign that we don’t live in a deterministic universe? You quote Ginsberg in the Review podcast, and his idea that a few epiphanies in life give us enough to live by.

FB: I’m not good at the big philosophy! But there is such consolation in little moments of light and kindness.

Fiona Benson’s Ephemeron is published by Cape Poetry. Watch the T. S. Eliot Prize filmed readings and interview, and read the reviews and Readers’ Notes online to find out more.

Jemma Borg

‘I wanted Wilder to be as much about what kinds of things hold us back from change as about anything else. Wildness […] is a process and we need to commit to living as a process.’ We talked to Jemma Borg about her magical and disturbing collection Wilder (Pavilion / Liverpool University Press, 2022)

T. S. Eliot Prize: Would you mind saying something about ‘weald’ and ‘wilder’, as words and their meanings – the ideas of the ‘place-present’ and a kind of ‘placelessness’?

Jemma Borg: The area I live in in East Sussex is part of the High Weald. The word ‘weald’ comes from a root shared with ‘wild’, and is an Old English word meaning woodland or forest. The word ‘wilderness’ used to mean simply a wooded area, a place outside of habitation, outside of the village, say. Though that place might have been the site for quests and initiations and a source of mythology, fairy-tale, imagination, risk. That said, to many indigenous cultures, wilderness doesn’t make sense – the world is home and this is a false distinction to make.

In the book, the Weald is both a specific location then, but it’s also a state of mind. As Gary Snyder said, as he made a contrast between the words ‘nature’ and ‘wild’, wildness is not an object or subject, but must be ‘admitted from within, as a quality intrinsic to who we are’ (my emphasis). There’s a curiosity and a fear about it. What waits to burst out of us in a wilder way? How are we wild – is it only in relation to the communal values of our culture? Is it about our animal nature? Is it threatening therefore? And do we not need to threaten the current order to envisage something new, a position where it is possible to behave in the interests of all life on this planet, and not just our own? Is it not a kind of coming home?

Much has, rightly, been made of the division that humans have made between themselves and everything ‘natural’ as though we were not ourselves natural. It’s so deep-rooted it can be hard to see this deeply flawed viewpoint for what it is – a wound as well as an error. Even if intellectually we understand that humans are part of a larger planetary ecosystem which we are profoundly affected by (and it by us), our Western culture at least seems predicated on this idea of separation, of rupture even, as though somewhere along the line we came to lose our connection with who we are and the planet that we are inside of and which is inside us.

I think what is interesting about poetry and any practice of attention is that they situate us in the ‘place-present’, the unending ‘now’. It’s a radical place to be because it’s transformative and challenging, and it’s also not really a place in the sense that we tend to think of it – it’s more of an event, both placeless, as process, but also conversely rooted in location as experience. Poetry and attention revel in naming, in observation, in the act of noticing, and that is how placelessness – or perhaps the erosion of strong selfhood, the dominant ‘I’ – is situated into a local context. The place-present, which I mention in the marsh thistle poem, means this kind of effervescing moment of life: holistic, free, absolutely ‘now’.

TSEP: It seems to me there is a balancing in Wilder, between stasis/stubbornness, a kind of indomitability, and dreaming/liberation/moments of extreme joy – ‘Marsh thistle’ balanced against ‘Wilder’, ‘The swing’, ‘San Pedro and the bee’; the ‘unbound’/’bound’ in ‘Portrait of shingle and wildflower’. Does that seem right to you?

Stasis/indomitability as a strength seems balanced against flow – the fresh spring in ‘Shadows and warriors’ with its ‘almost crystalline smoke, making ladders of freshwater / and shock in the warmer salt’ of the sea into which is runs; the ‘positive unravelling’ of ‘An anecdote for September’. Still there’s a kind of spiralling duality, isn’t there – water (or perhaps what human activity has water do) can be a problem too, as in ‘Little rivers feed bigger rivers’…

JB: I would agree there is a tension or contrast between stasis and movement or flow – and this is one of the driving forces in the book. I think this is about distinguishing between what seems evident as being part of life – a sense of process, movement, a not staying still, which is wildness if you like – and stasis which is the fossilisation of attitudes within us, for example, that is to be challenged and which represents, at its extreme, death. So, a tree is indomitable in its desire to grow – life is relentless, rampant, ready to spring up everywhere given half a chance. But stasis is the opposite of that – a kind of unwillingness to ‘be wilder’.

Without Snyder’s ‘etiquette of freedom’ – the ethics of learning to live in a way that is not primarily led by the ego, a way that is naturally found by being in contact with what he calls ‘wilderness’, but perhaps with the non-human in particular – the risk is getting stuck in a limited worldview, one which permits us to do devastating things to the planet. Perhaps we all go a little bit mad, like a big cat in a cage, when we don’t have contact with the earth beneath our feet. Never mind contact with true ‘wilderness’ as we mean it today – which if we define it as being pristine, free of human contact, doesn’t exist anymore, except perhaps in our imaginations. It’s also worth saying that some of the most pristine areas are – or have been – inhabited by indigenous cultures who have acted as caretakers over thousands of years.

TSEP: In my reading of your interview on the Pavilion Press blog, you oppose anthropocentrism (an outcome of which may be said to be the Chernobyl disaster you write about in ‘The engineer’), the separation of human existence and, well, everything else. It seems to me Wilder charts a widening, deepening engagement with a biocentrist view of existence. Is that right?

JB: I do subscribe to the view that centring everything around humans is a viewpoint with error and even moral deficiency. From my training as a biologist, it’s a natural position to take – the human isn’t the only story being told, if you like. The idea of deepening or widening our sense of empathy, care and rights to include all the non-human world is an inevitable development from that.

It’s instructive I think to contrast what we used to call ‘conservation’ with the newer movement of ‘rewilding’. Conservation often sought to protect specific species or habitats, keeping things in a static position, freezing them as if in a zoo. One of the problems was that this approach often seems to have been about preserving species we humans decided we like over others – the cute, cuddly ones, say. What has become clearer is that not only is it questionable to prioritise one species over another, but that in order to keep our planet healthy, we need to think about the larger scale ecosystems over considerations of single species. So, rewilding is a giving over of land to process, which results in a richer ecosystem, and perhaps not in predictable ways – it’s a process of discovery. The result seems to be more complex, functioning and wild compared with the old ideas of ‘preservation’.

TSEP: Can you say something about the structure of your book? Some of our poets have named sections, you have blank pages – pauses, not chapters?

JB: My editor, Deryn Rees-Jones, was very helpful by disrupting my initial plans to divide the book into two halves. As things progressed, I didn’t want to break the book into hard sections, but just to pause, that’s right. There’s a movement in the book which has been both discovered and constructed and that’s not only as a form of narrative but also in terms of pacing, and it seemed that the poems naturally divided into sections.

Form on the page is a kind of listening and the larger structure of the book is also about listening to the poems themselves. The blank pages create this visual pause and I liked not only constructing how the book begins and ends – how the very first and last lines of the book speak to each other – but also how the last and first lines of poems talked to each other across the pauses. The pauses are like ‘wildlife corridors’ for ideas to pass freely from one landscape to another perhaps! The juxtaposition is always interesting.

TSEP: I love Jeff Van der Meer’s wonderfully unsettling and fantastical Southern Reach trilogy and perhaps there’s something of his Ovidian metamorphoses in your ‘heavy as a tree / landfalling onto sand / and the curved world catches you’ (‘Wilder’) and ‘I’m filled with bees’ (‘The swing’). Was the ‘ecological uncanny’ in your mind?

JB: When we look at the non-human world, there’s a sense of unfamiliarity that is rather exhilarating but also – as we come to recognise all that is wonderful and unique about non-human life – we can see the similarities too. We have this particular superiority about language, for instance – that it’s unique to us – whereas it’s actually inherent in non-human life, even if other non-human languages are not the same as ours. Clearly, humans have a particularly complex language – and being able to write it down and record it is of huge significance. But let’s not assume that animals are ‘dumb’ because they don’t talk as we do. Communication is complex and multifaceted and we’re learning so much more about how other living organisms do communicate – the ‘wood-wide web’ is a recent example – and that ought to challenge any arrogance.

Writers such as Alice Oswald have actively asked how we can give voice to the non-human. I do think one of the ways is not to deny the human and to accept the fact that we can’t escape our perspective, but to realise that organisms are indeed both alien and familiar – and ultimately, we are all built from the same stuff, we are far more alike that we tend to think, and the fates of all of us – human and non-human – are intimately tied together. To see the human in the animal is quite right in a way, and to see the animal in the human equally so. It makes me think of the prehistoric cave paintings where a human face stares out of a bear’s or an antelope’s body – what’s interesting is the unstable boundary between us and the other, which reflects back and forwards, melds our identities, celebrates different ways of being and knowing. I think fluidity of this kind is important for us to have a fullness and authenticity of experience – and is part of returning to that sense of the wild within us.

TSEP: You cite many influences in the book, poets such as Gerard Manley Hopkins as well as writers and thinkers from non-literary fields. Bashō provides some comfort in the otherwise discomfited ‘On sleep’. Do other writers help you organise your thinking? How consciously do you think of them as you write?

JB: Yes, we talked about art as a conversation, didn’t we? None of us lives in a vacuum. I think it’s a gesture I learnt from science where you cross-reference everything – that’s part of the way of making a scientific argument, part of the rhetoric of it, because you are building on and acknowledging what has gone before you – it adds to the credibility of your own work because it gives context. But also it shows that perhaps nothing is truly original, just reinventions, variations on a theme, dependent on what has gone before. And that is what life is like, bubbling over with the same solutions to things – like evolving eyes for seeing – but each variation is so wonderfully different. I don’t generally consciously think of other writers when I write but I do like finding the connections later on, in the editing process. Finding sympathies with the discoveries of others, to bring in those connections, is to make a kind of network, or ecosystem, of the imagination’s work.

TSEP: ‘The thought-deep grass’ and ‘the forest’s logic’ set against ‘An unravelling of moss, lichen, reindeer, caribou, // humans, cod, seal, walrus’ – we have to listen and think differently to avoid climate catastrophe, don’t we?

JB: Certainly, business as usual will not do, and I’m sure our natural propensity for denial doesn’t help and that any strategies that we can use to face up to what we don’t want to look at directly are absolutely essential to being able to make the kind of changes that would see the mitigation of climate change or the halting of the loss of biodiversity. We’re needing to tackle our own greed in the West, yes, but also our reluctance and fear of change.

It’s been said that story-telling is essential to our response emotionally to the devastating facts about the climate that science tells us very clearly. Without that kind of emotional response, it’s very hard to do what needs to be done, to hear it perhaps – we are very comfortable in the same old routines and full of inertia. The fact that story matters shows the importance of the participation of our imaginations. I wanted Wilder to be as much about what kinds of things hold us back from change as about anything else. Wildness, as I’ve been saying, is a process and we need to commit to living as a process. Psychedelics – which have been used for thousands if not millions of years by human species – are instructive in this way. They enable the imagination to conceive of different ways of being and they rightfully do so in a context of community. But any way we can find to reconnect with our deeper selves, needs, desires – this is how we might find the capacity within ourselves to rewrite the narratives which underpin modern existence and its sense of what is important. And so much of it comes from a willingness to stop and be attentive, to listen – such simple things.

Jemma Borg’s Wilder is published by Pavilion / Liverpool University Press. Watch the T. S. Eliot Prize filmed readings and interview, and read the reviews and Readers’ Notes online to find out more.

Victoria Adukwei Bulley

‘I wanted to take each of these moments as emblems of a quiet but rich life and place them on the mantelpiece of the interior, to sit with them and call them sacred, and affirm them as safe.’ Victoria Adukwei Bulley talks about Quiet (Faber & Faber), her debut collection shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2022

T. S. Eliot Prize: You have really thought-provoking epigraphs: ‘this reach towards the inner life, that an aesthetic of quiet makes possible […] a black expressiveness without publicness as its forebearer, a black subject in the undisputed dignity of its humanity’ (Kevin Quashie) and ‘… you got to hold tight a place in you where they can’t come’ (Alice Walker). This touches on the Big Theme in your book – but might you like to say a bit about it? What is the place Walker refers to?

Victoria Adukwei Bulley: That place, as I perceive it, is an interior landscape that might even be described as a forest or nature reserve of the self. Everything from the mundane to the sensual and the cerebral has a place in that landscape, and I wanted the book to be capacious enough to hold each of these with respect – so that it could contain a kaleidoscope of moments that make up a life. Whether that’s a speaker reminiscing upon her time at school, or enjoying the company of good friends (complete with the kinds of language, laughter and in-jokes that happen here); or being with a lover; thinking about a crush; thinking about history, the state or abolition; experiencing a miscarriage; everything from watching a cat at play to watching a snail sleep. I wanted to take each of these moments as emblems of a quiet but rich life and place them on the mantelpiece of the interior, to sit with them and call them sacred, and affirm them as safe.

I use the word ‘safe’ because the book is rooted in a black subjectivity, particularly that of black girlhood and womanhood. This is a subject position rich with creative agency (as echoed through many of the other epigraphs in the book) but, given the racialised and gendered structural realities of the world, insisting upon that agency involves risk, as the third part of ‘fabula’ explores. At the same time, the book is not an attempt at transparency, at a redemptive representation in which the subjects demand recognition of validity or humanity. To me, the speakers of the poems always hold a little something back. They keep one hand in their pockets, they aren’t always facing the camera – sometimes their backs are turned completely. The subjects are more concerned with becoming known to themselves than being known. This is their reward, whether it’s witnessed or otherwise.

TSEP: The organisation of your book and the enigmatic section titles are very interesting. There’s the suggestion of progression beyond a door, a lock into a garden, a journey deeper into the interior, a garden, a landscape, towards a meditative, more confident self. Keats’ ‘Mansion of Many Apartments’, the progression from ‘the infant or thoughtless Chamber’ came to mind…

VAB: The progression that happens as you move through Quiet definitely has much in common with the spirit of what I understand Keats to be talking about. My intention for setting the book out as a progression through rooms separated by brief poems that operate as keys, doors and seals was for myself as the writer, as well as the reader. In the early stages of putting the book together I knew that I as the author also wanted to travel – to find myself, by the end of the book, at a new position with a greater sense of possibility and direction than before. In its most obvious form, the idea of a house reflects the interiority that the book takes as its focus. But the organisation of the text was also itself a provisional map, a blueprint – an experimental framework that I imagined and then wrote into (with no guarantee of success!).

I thought about how I wanted to feel at the close of the book. I called that feeling a ‘garden’ because the image this conjured felt sensorially accurate. The risk was that in order to write the poems that would go in this section, I knew that I would have to actually arrive at the garden – emotionally, intellectually – so that I could write poems that were honest and reflective of ideas I truly felt and believed (and not just as sterile, abstract concepts). I didn’t know if I could get there but one of the ways that I did was through the things I was reading, which gifted me that sense of possibility that I had been yearning for. I wanted to pass this gift on, so I included a selection of these books in the ‘Further Reading’ list at the end of the collection. These are some of the texts that guided me to that ‘night garden’. Some of these authors are the ‘luminaries’ I see as working together in that night garden.

Coming back more squarely to this passage from Keats – and it’s been a long time since I’ve read Keats in any depth, so I’ve had to brush up on this slightly – I think there’s a very real commonality here, particularly in that sense of moving through ‘chambers’ of knowledge and understanding. But I’m especially drawn to the words ‘… we are in a mist’. We are in that state, we feel ‘the Burden of the Mystery’. In ‘fabula’ and across the final section of the book there’s a lot of mention of darkness, and while that darkness is reflective of the looming apocalyptic time in which we live, it’s also at other times darkness that’s also of richness and depth, of a mist-like unclarity that asks of us that we develop new vision, new ways of being and being-with one another that are not fearful of the unknown. There is a need to befriend that mist so as to get through – survive – that burden of the mystery. I see this in that passage from Keats, and likewise in his concept of ‘Negative Capability’ which is something I feel incredible affinity with.

TSEP: There is a circling/reordering of a door, a seal and a key in the section heads too. Perhaps these suggestive and mysterious devices connect with the equally mysterious black mirror?

VAB: I think this is accurate – even if not entirely deliberate or conscious in relation to the black mirror. I wanted the book to have recursive elements, to have a sense of progressions, of coherence, but also of echo. I thought that this would create a growing sense of familiarity within the reader that makes the book feel immersive and possessed of its own logic. And so the circling is a big part of this.

TSEP: You have talked about Quiet being written in a fairly concentrated period after you’d read, at the recommendation of Lynnée Denise, Kevin Quashie’s The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture. So, was the book written out of the ideas that reading Quashie freed up?

VAB: I would absolutely say that Sovereignty was a catalyst for Quiet. The lines I was thinking along before I came across Kevin Quashie’s work were more about the difficulty of speaking, of language and its slippages, of how words fail. This isn’t too far afield from the book that exists now. Many of the poems pre-existed my reading of The Sovereignty of Quiet but while I had an established thematic focus it was much more vague and had less of a motor. Encountering Quashie’s work was a lightbulb moment because I felt that his work described not only a poetics that my work embodied but also that it provided a language for many of the ways that I had seen myself experiencing life – ironically as someone who had so often been called ‘quiet’. There was a very particular loneliness that his work removed from me. This was a gift that allowed me to write without over-compensating, without apologising for that quietness. And actually to take that very quietness as a subject and really toy with it, look at it from all angles, and see what else it holds.

TSEP: Hair memory (‘Epigenetic’) – (which had me thinking of Pixar’s Inside Out!) – ‘someone written in you / still knows what it felt like’. Can you say a bit about this?

VAB: When I was little I used to think that hair was like paper coming out of a printer, that it contained records of our every thought and all you had to do was find the right strand and you could (with some kind of technology) scan and replay an experience like a videotape. But also, yes – there’s a lot of hair in this book: hair as recalled from childhood, hair found in food as interruption, hair as a riff on the word heir, hair as a place into which seeds were literally sown, hair as an inherited trait, and in excess of the book, hair as something shaven off in grief or mourning, biblical hair as Samson’s strength (and downfall)… etc. I think hair has so many significations that it was impossible not to have some of my fascinations about it arise in the book. It’s a very mysterious part of our bodies.

TSEP: Air (in ‘six weeks’: ‘leaving brief & careful tellings on the air with my breath’, and ‘the unreadable air’ in ‘Air’) and hair (see above) recur in the book with a kind of a rangey metaphorical resonance. Was this a very conscious part of your planning of the book? (Water is there too!)

VAB: The instances of air are much less conscious than those of hair. I wouldn’t say they were planned at all. Water, on the other hand, like the hair aspect, probably has more of a charged meaning in my consciousness and so while this wasn’t deliberately included as a theme or recurrence, it doesn’t surprise me that it’s there – ie I have a long lyric essay titled ‘On Water’ online at The White Review and so elements of that thinking are unlikely to have been far from the surface. But not planned.

TSEP: ‘The Ultra-Black Fish’ – the scored out words are ‘discovery’ and ‘discovered’ – why?

VAB: I wanted to blatantly make a correction in the text that would loudly deny the validity of that word but also signify how easily it would be used, and to correct my own impulse to use it. Captured was an important replacement because I also felt that it was more true.

TSEP: ‘Shut up about Freud’ (‘Dreaming is a Form of Knowledge Production’). Me too! But what do you mean?

VAB: My sense is that Freud is overrepresented in how we think about dreams (and many other things). Not irrelevant but overrepresented. I also felt like this last sentence struck me as the kind of thing you’d hear someone say in a dream completely out of context before you wake up.

TSEP: There is a lovely idea in ‘Dedication’: ‘we are always // accountable / to the stranger // on the skyline’. Can you say something about this?

VAB: I feel that we are answerable to people that we’ve yet to even meet but know will be coming our way. The idea of being accountable to a stranger is strange perhaps but it’s an idea that feels worth practising, especially if we imagine ourselves as once having been that stranger. The warmth of not needing to be known in order to be cared for; to be cared for as a given, even when still in potentia.

TSEP: In our video interview, you talked about some of Quiet taking the mick and it is often slyly funny – in for example ‘The Ultra-Black Fish’ and ‘note on exiting’ (I love ‘ the [ ] supremacist capitalist [insert -ist] [insert -ist] patriarchy is working faultlessly today, running at full service; no disruptions, even with your small axe in its back’).

VAB: Humour is key because I do feel that the book demands a lot at times. It’s quite text-heavy, sometimes theory-heavy, and formally unpredictable. So – even for myself – it’s helpful to keep the jokes in because they offer moments of lightness but also because they are another way of being honest. They are a way of handling the truth whilst also admitting its absurdity.

Victoria Adukwei Bulley’s Quiet is published by Faber & Faber. Watch the T. S. Eliot Prize filmed readings and interview, and read the reviews and Readers’ Notes online to find out more.

Philip Gross

‘We are all desperately and rightly confused and unsettled about what’s going on around us. Is that a comfort? No, perhaps not, but it is life’, Philip Gross comments in his T. S. Eliot Prize interview film. We asked him about his shortlisted collection The Thirteenth Angel (Bloodaxe, 2022) – and how poetry can help

T. S. Eliot Prize: Was ‘Nocturne: The Information’, the long opening poem in The Thirteenth Angel the one that lit the idea or ideas for the book? At the online launch of your book, hosted by your publisher Neil Astley of Bloodaxe, you talked about a collection forming as a process of ‘gravitational clumps of things which start being in relationship with one another’. Could you expand?

Philip Gross: ‘Nocturne: The Information’ came to be written as most of my things do – by existing as fragments in a swirling, all-angled, ongoing notebook with no pressure of expectation that they become anything at all. Far from being the idea for a book, it wasn’t even the idea for itself at the start.

It was six months after a stay of some weeks in Finsbury Park before I looked back into that material, and seemed to see an emergent shape and voice among them, which I hadn’t been aware of at the time. That’s what I meant by the gravitational clumps – the way that asteroids or planets appear to have formed. The interesting thing is not so much the inert material, but the force that patterns it.

Sometimes a form on the page helps to reveal that patterning. The staccato, rather breathless sweeping over the sensations in the opening lines offered a shape that was constrained but with built-in fractures. That became a vehicle for episode after episode. Or maybe a channel (with built-in disjunctions, like weirs on a stream) down which the poem can flow.

What the selection in a relatively short reading couldn’t capture was a kind of urgency that drives on through the sequence as a whole, the echoes and coherences that crept up on me as I wrote. I hope I got a little of that into the reading anyway.

TSEP: You read with Aleš Šteger at your launch, and he and Neil talked about other angels in film, literature and philosophy – Wim Wenders’ angels in his film Wings of Desire, Rafael Alberti’s angels, Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History. In response, you talked about the artist Paul Klee’s ‘playful’ angels, less the ‘tragic onlookers’ portrayed in Wenders’ film. Can you say a bit more about what your angels represent, what as a motif they helped you articulate?

PG: Wim Wenders’ angels were consciously there by the time the book was taking shape. The cover image nods in that direction. I’ve lived with Klee’s angels for a long time – playful, yes, but the great rush of them came when he knew he was already, slowly, dying, and some of them do partake of the violence building in the world of 1939-40, too. I hadn’t encountered Alberti, and I’m hugely grateful to Aleš for that. And angels were appearing in the cracks of the poems, in the form of incidental metaphors, for a long time before I noticed, let alone thought ‘motif’.

What mine ‘mean’ stays, I think – I hope, just a little beyond my reach. We could start with: the ability to surprise, to make the very ordinary a revelation, to upend our perspectives, maybe throw us outside of our everyday selves, looking back or looking simply further – to be a moment of intense presence and, also, not there when you blink.

TSEP: How did the ‘Thirteen Angels’ sequence evolve? Is the way that it did typical of your writing process?

PG: The evolution of ‘Thirteen Angels’… I hesitate to call it a method, but there’s a habit of thought here that comes naturally to me: walk around a subject, question, object, concept from multiple angles – you could call it many takes – assuming that the truth is in the ensemble of them more than any single view. Imagine a voice saying ‘Yes… And on the other hand…? And what if, then…?’

TSEP: You described being in the flat in north east London during the pandemic, where you began to write, as a gift. Can you say why? Neil Astley observed that the urban scene has not been typical of your work to date.

PG: Neil is right(-ish) to say that urban scenes are untypical for me. There are exceptions – my 1993 collection Scratch City (for young people, nominally, but adults as well) was very much immersed in urban Bristol, where I lived then. Since then, there’s been a lot of water; crossing the Severn estuary nearly twenty years ago (as in The Water Table) and living now beside it has been fundamental in a way I still can’t quite explain.

The discussion I had with Aleš Šteger at our launch, about me rediscovering a certain amount of foreignness, felt revealing – and was certainly not planned in advance. That may be a clue. To find myself intensely in that place, above Stroud Green Road, but not exactly of it – home-making, but not being at home – was the gift. Maybe the sheer physical hard work of it, and being stripped of our usual habits, played a part, too.

But I’m wary of equating the subject matter of a poem – the material – with what it’s about. There might have seemed to be a change of subject from The Water Table to the book that followed it, Deep Field, about my father’s old age and loss of language. But in the writing they felt all of a piece to me, to do with shifting or dissolving boundaries of our selves, with what we’re part of, and (increasingly, of course, with older age) with letting go.

TSEP: In the film interview you did for us, you talked about the ‘trusting the proudly ageing body’. Can you say what that means for your writing?

PG: The line about the ‘proudly’ ageing body is a little defiance – the nagging pains and malfunctions of it are a bugger, of course. It was at least an assertion that our validity or value doesn’t depend on how long we can look or feel young. I’ve never felt wrong to write from the moment, the life-stage, I’m in. No assumption that time brings wisdom, certainly – just a kind of relativity. The physical facts of my eyes, skin, brain and all the senses, as well as the bank of memories and associations, richer and faultier as time goes on – all this forms the lens for me now, which will see something particular, till the moment shifts and moves on. And meanwhile the world is changing too.

TSEP: You also say this striking thing in the film interview: ‘This is the first time I’ve ever been here, in the me I am in the world I’m in now. We are all desperately and rightly confused and unsettled about what’s going on around us. Is that a comfort? No, perhaps not, but it is life.’ You may be referring to the pandemic or the climate crisis or the war in Ukraine, politics or the economy. How does poetry help?

PG: Can I even separate the strands of strangeness and unsettlement? The pandemic itself, of course, but also its deeply ambiguous way of not-quite-ending… And yes, the sense that the margins of error we thought we could rattle around in, in environmental terms or in the geopolitics of Europe, are suddenly narrowing sharply – just like my and my loved ones’ health, at the age I am, things could suddenly fracture. Deeper even than that, the sense of possibly unbridgeable disjunctions opening between people not just at the level of opinion but of their whole construction of reality, as algorithms feed us with confirming evidence of whatever prejudice… And real questions about what being human will come to mean as it becomes a (paid-for) choice how we can remould our biology, alongside a cast of AIs, avatars and outright deepfakes. And so on, I’m tempted to say.

How does poetry help? By surprising us with the possibility of fresh perspectives. By being a place we can be, in a resonant space, to let the swirling of sensations settle. By offering sudden rises in the ground from which the view is longer… The shade of a palm tree in a desert. In turbulent sea, islands of clarity… (All of a sudden this starts to sound like my answer to the ‘what are your angels?’ question. OK. So be it. Stet.)

Philip Gross’s The Thirteenth Angel is published by Bloodaxe Books. Watch the T. S. Eliot Prize filmed readings and interview, and read the reviews and Readers’ Notes online to find out more.

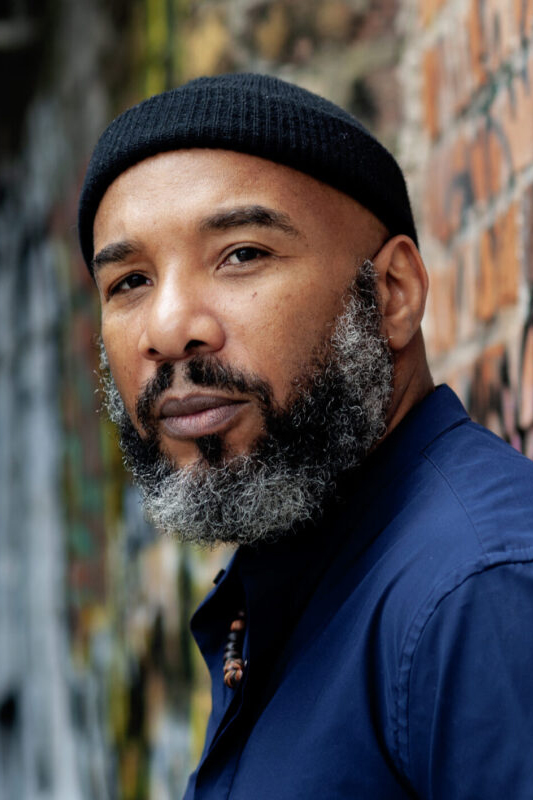

Anthony Joseph

Anthony Joseph’s Sonnets for Albert (Bloomsbury Poetry, 2022), shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2022, explores the difficulties of truth-telling and how this can be overcome by love. We spoke to Anthony Joseph about his collection

T. S. Eliot Prize: What would you say Sonnets for Albert is about?

Anthony Joseph: There are layers. On the surface, it’s about my relationship with father, my relationship to what I think I know of him, to memory. I’m creating a sort of fragmented, non-linear biography of him; the book as a holding place that contains and holds him while I try to make sense of what he was to me.

But at its heart the book is really about loss and love, I think love is the main theme – the capacity to love, the way we can love unconditionally where a person’s humanity, their substance, is so strong it displaces their questionable aspects. My father wasn’t great as a dad, but I loved him, was fascinated by him. Readers have asked how, or why I could write a book about someone who was not a good father to me. But that’s the point. I needed to write this all down to make sense of him and the impact of his absences on me.

TSEP: Christopher J. Griffin has written a very interesting article on your non-linear approach as a writer. You take many routes to build the story of your father: your own (unreliable) memories; the sometimes contradictory memories of other family members, friends and neighbours; and photographs, many you’ve taken over years (not presented chronologically), some old family photographs – a wedding photo of your Mum and Dad, a passport photo. The effect is something like the poetry equivalent of funeral chat, with everyone bringing their different experiences of a person to the moment. Could you talk about this?

AJ: Death has the tendency to push the defining aspects of character into focus. Death is a caricaturist. In our loss we grieve for the things which were good. So I remember the good things about my father – his style, his charisma, his laughter, and I focus on that. I also have a rule that I live by as a writer, which is, if you are writing something that you know will hurt someone, don’t write it. My sonnets for my father were not the place to crush him under critique. We spoke about this, well some of it, in person.

Equally, I believe that a biography is only a beginning. And, as a Caribbean writer, my focus tends to lean on the communal. Perhaps, because our history has been characterised by an us and them strategy for so long. It was us, the colonised as a homogenous entity, against or under the colonial power. Things have changed somewhat, but I still think that the best way to tell the life story of someone is to seek out the voices and memories of those who knew them. One voice – my voice – cannot hope to render enough of an angle around my father. To show more angles, to shine more light I needed to speak to other people who knew him. The contradictions are useful, since the truth – if there is a truth – lies somewhere between the conflicting versions. The imagination of the reader brings their own experience as a coefficient, filling in the soft spaces of the poems.

My father was a charismatic loner. Is that even possible? But he was. And he was awkward and reticent with affection. In my book I try to evade his evasions, to approach much closer than he would let me in his living time.

TSEP: So you apply formal means – the sonnet and photography too – as mechanisms to frame or control what remains difficult to fix. Is that right? Did finding your thoughts and responses through the sonnet, especially as you wrote more and more of them, become a very natural process? Or have you reorganised and polished the poems endlessly?

AJ: I write poetry incrementally, most of the time at least. Though sometimes the universe says, ‘Gosh, you’ve been working so long at this poetry thing. Here, just have a poem, go to bed’, and then the poem comes fully formed. But generally I can work for many years on a poem, on a collection.

A lot of these sonnets started out as strict form Shakespearian sonnets. I was drawn to the traditional form for its discipline, for its potential for austere tone, for the confines of its form – in a kind of Oulipian way it can be poetry by permutation and constraint. I saw it as a place to wrestle my memories of my father into the shape of a poem. Control – the rigours of the strict form dictating a path. And for a while this worked well.

But the Shakespearean sonnet is an imperial form that tries to convince you to frame your argument in a certain way. For me, the subject matter resisted this, and after a few months, the poems demanded a looser leash. They started to shift into something else, something more Caribbean, more like my Dad, and I just followed.

It’s like a saxophonist having to navigate the keys and rituals of playing scales before they can learn how to play free. And even then you aren’t totally free since you’re using the tools you learned from form to be free, and the sonnet remains a sonnet.

Anyway, yes, the poems were polished and polished, until I grew nauseous from editing and abandoned them, and they do attempt to ‘fix’ their subject into form and so, into historical space. As James Salter says, ‘[…] everything is a dream, and only those things preserved in writing have any possibility of being real’.

TSEP: Your Dad was fugitive and photographs both fix and fade. Was the inclusion of the photographs and the way you describe yourself photographing yourself in the poems – emphasising the distance between photographer and subject, son and father – a very conscious idea?

AJ: Yes, the photos are, like the poems, paths towards a glimpse into the soul of my father, which is really about how my gaze bounces back from him, reflecting me in the mirror of the eye. I mean, we are who we are because of others, so too, I know myself partly from what I imagine my father’s image reflects. I think. There is something curious about photography and time. In one sense a photograph fixes time, makes it stand still. In another sense it extends time infinitely. In looking at a photograph I took of my father – and I took dozens over the years, always trying to hold him – I am drawn back to the moment, which now extends, emotively and visually, into the present moment; the photo acting in this instance, not as a monument to time, but as a time machine, manipulating time itself. I felt that the photos, too, told the stories the poems could not. They captured and hopefully transmitted parts of his personality in a way I could not capture in words.

TSEP: Is it love that closes the distance, unravelling the mystery and mask?

AJ: Yes. It is love. Love is the reason I could write this collection. I fell in love with my father early in life. There is a short poem in my first collection, Desafinado, called ‘Clark Boots’: it is Christmas Eve and I have found a present my father has brought for me and tried to hide in my bedroom. He comes into the room and takes the cardboard box from me. He smiles and just says, ‘Nope’, and stands on the dresser to put the box far from my reach. It’s one of my earliest memories of him, but I remember how I felt, the way I looked up at him, his bellbottoms, his Clarks desert boots, the way he smiled at me. My father, when we were together, never gave me cause to feel anything else but love and laughter. I was both mesmerised and confused by him. I think that is love. And I think love is what closes the gap as I move from the outside, into a close up of him – the poem, as close as I can get to him and to myself.

TSEP: Your parents’ wedding photo is the cover of your book Teragaton, published in 1997. Is there a connection between its use there and in Sonnets for Albert?

AJ: Yes, in both I am in the image. In Teragaton the photo was used as an allegory for what that book was conceptually about. At the time I was interested in surrealism and what I called the ‘core text’, the unconscious text. My existence as a hidden but potent being, hidden within my mother echoed this idea of a core, non-visible text. The word ‘Teragaton’ had come to me in a dream, whispered by my recently deceased mother, walking backwards up a hill, so it seemed apt to have her there.

And now, in Sonnets… they are both gone; joined together in the gone momentum, so the photo – in which my mother is 18 and my Dad 23 – and the two poems in which they feature, complete a symbolic cycle and bring them together for a final, perpetual time.

TSEP: The book is about self-exposure too. In one of my favourite poems, ‘El Socorro’, you recognise your father’s forearm and fingers as your own, in ‘Rings’ you compare your hands to his, and In ‘The Trembling unto Death’ you recognise his dark moods and lightness as your own. Is this to do with the lost physicality of your father and/or the recognition of our own mortality when we lose someone we love?

AJ: Yes, that’s true in both cases. I think when a parent dies we are forced to reconcile with our own mortality. Both my parents have now passed. My mother died at 47. There are places in Sonnets where I speak of my own mortality, and the body within this motion, and my children, and their cycle.

I remember arriving at the funeral home where my father lay, early morning, I was the first to arrive, and the receptionist took me upstairs and just opened the casket as if she was opening the bonnet of a car, or a cake box lid. It was strange being confronted with this body. And I touched him, felt the rigidity of his chest. It was almost invasive.

The mood swings and darkness, yes, my brother, my father and I all suffered/suffer from this. I’m not sure if its genetic. But there is, equally, lots of brightness too, and I have inherited some of my father’s hedonism and naivety.

TSEP: Can you say something about the blank pages through the book – why are they there?

AJ: Space. The collection is filled with so many moments of loss, sadness, so much heavy imagery. The blank pages, I hope, give some respite to the reader. A breath. They are also filmic, like the closing of a scene, a transition into the next. I’ve always thought of poetry as a visual art as well.

TSEP: When we met you said that you were telling a story that might otherwise remain hidden or untold or be lost – and this has been the case with Caribbean lives and history. Would you expand on that?

AJ: As Caribbean writers, we often become the historians, keepers of heritage and collective memory. And the best way of doing this work of universality is by being as deeply personal as you can. The personal is the universal. Oral history fades and dies; unless they are written down the things my aunt, my grandmother or my father told me, they are lost. The same is true for Black artists in the UK, as Pearl Connor once said, ‘In Britain there is no record of the contribution we have made to the performing arts. […] There is no memory in Britain for us. There is a hole in the ground and we fall into it.’

But why should our existence and contribution be so temporal?

I think that as a primarily Caribbean poet, I am not only retrieving and holding our histories, I am also extending Caribbean and Black British lives and thought into the future. I inherit the responsibility to be historian, story-keeper, biographer, recording and keeping what is so easily lost or forgotten.

My book Kitch was an attempt to do this. Lord Kitchener was a musician who arrived in the UK onboard the Empire Windrush in 1948, he made music for about 60 years, recording 100s of songs, and contributed our understanding of what it means to be Caribbean. And yet, when he died in 2000, there were no biographies, no real accounts of his life, no one place where anyone could view or listen to a discography. So I decided to do it. Same with my father – even though he’s not as culturally significant as Lord Kitchener, it was still important to document some of his life, the life of a Caribbean man, in Sonnets for Albert.

Anthony Joseph’s Sonnets for Albert is published by Bloomsbury Poetry. Watch the T. S. Eliot Prize filmed readings and interview, and read the reviews and Readers’ Notes online to find out more.

Mark Pajak

‘For every one poem I feel is successful, there are an inordinate amount of failures behind it […] my process is glacial – it can feel like something akin to erosion’. We spoke to Mark Pajak about the making of Slide (Cape Poetry, 2022), his Eliot Prize-shortlisted collection

T. S. Eliot Prize: Would you explain your collection’s title Slide?

Mark Pajak: I’m awful at titles. My poor editor at Cape, Robin Robertson, was subjected to some utterly crap efforts. Mercifully, he is a master writer and mentor. He pointed out that there is always movement, often critical movement, in my poems, so we experimented with verbs that suggested a slow decline, collapse or unsteadiness: slipping, slippage, slant, inclining, subsiding, keel, The Keeling. ‘Slide’ stood out to me as I keep returning to childhood, or innocence and the loss of innocence, in many of these poems.

TSEP: People are doing dangerous, sometimes fatal, things in Slide and time stretches at the point at which these are about to happen. Can you say something about drama and storytelling in poetry? Can you say why that pivotal moment (or threshold?) interests you so much?

MP: I keep thinking about that (often comedic) cliché portrayal of a coward: someone raises a fist to hit them and they wince and scream, ‘Not the face! Not the face!’ A fear of being hit in the face is perfectly rational and, probably, inbuilt. When it happens, it’s bad: there’s that explosion of white in your vision, you’re stunned, you’re queasy, the pain is overwhelming. I wouldn’t recommend it – but by far the worst part is the anticipation. Someone raises a fist and then fear and hope exist simultaneously in that fight-or-flight moment – possible pain and possible reprieve. Threat is intensely evocative and the foundation of most suspense in storytelling. Just as slow motion in a film can hold the viewer in a moment of suspense (the inexorable approach of the Terminator comes to mind), so a poem can stretch time just before a pivotal moment, heightening the threat and allowing the reader to wallow in the complex and conflicting emotions that anticipation of danger can evoke.

TSEP: Your book works the uncomfortable border between being a bystander, a voyeur even, and being a witness. Is that the moral imperative of your work – to test the reader’s impulse, what Mary Jean Chan in her Guardian review describes as ‘our shared complicity’.

MP: In Year Eight I was waiting for the school bus when my little sister was shoved over by an older boy. My sister, tearful, looked up at me and asked for help but, for one reason or another (maybe because the other boy was much bigger or because there was a crowd), I just stood there and watched until the older boy left. I am intensely ashamed of that moment. Maybe I shouldn’t, necessarily, have hit my sister’s bully, although there’s a lot that can be said for kicking someone in the shin and running away. But at the very least I should have reflexively reached out to her in her moment of pain and embarrassment. Since then, whenever I have succeeded (consistently, mostly) in acting or speaking out instead of standing by, it is because choosing to not act when my sister needed help was a defining moment. I come back to that memory, with all its complexity, again and again.

TSEP: Does your epigraph by John Berger suggest that animals know more than humans? I see this in ‘The Knack’ – in the cow’s look, ‘her lens full of staring dark’, and in ‘Brood’, those watching ‘thousand-thousand birds’. What do animals see that we have forgotten?

MP: I wouldn’t say animals know more than humans, or vice versa. Each animal has its own depth and flavour of knowledge. However, eyes are interesting. Humans read a lot into a look. I heard recently that some paleoanthropologists have suggested that humans have such a pronounced eye-white, when compared to other great apes, because eye-contact is so vital to us and that ring of white helps us to find, then lock onto, eyes much more easily. That’s not to say that other animals don’t register or react to eye contact. However, it’s not unusual for humans to interpret human-like feeling or communication in an animal’s look. Also, how alien we consider an animal might have a lot to do with how dissimilar its eyes are to our own. Eyes are (excuse the pun) where we see ourselves in animals, it’s a place where we can attribute humanity to something non-human. So I like to draw attention to this in places where we often show the least humanity – battery hen farms, slaughterhouses etc. There is something almost accusatory in that Berger line that resonated. However, it is only accusatory depending on our own actions – it could, just as easily, be the opposite.

TSEP: You use brilliantly precise language (especially in your metaphors), and there’s a Hitchcockian inexorability in your descriptions: all those captured reflections, lines like ‘a distant train split the air along its seam’. You talked a bit about your process at the Eliot Prize filming day. It’s a carefully worked progression by the sound of it. Does something surprising happen occasionally that unlocks a poem?

MP: I often kill poems by overworking them. To produce this book, I kept a routine of early mornings and a daily quota of hours writing (three, minimum). Usually, a poem will reach a stage where it’s gone too far from whatever the original spark was and falls flat. Each draft becomes deader and deader. I save all my drafts and, when this deadening hits an inevitable wall, I look back through the iterations to see if anything is salvageable – a stanza, a line, a turn of phrase, image or concept. Then I begin again on something new (the first day on a new poem is horrendous – I start up my laptop and stare at that infamous blank screen and just… sweat). Only once in a great while does a poem actually come right and the final draft is, without fail, unrecognisable from the initial idea (‘Crystal’ began as a poem about a wasp sting). It’s always a surprise. No two ‘right’ poems progress in the same way (the poem ‘Cat on the Tracks’ took a long walk in a strange town to finally resolve, ‘Thin’ took a chanced-on news report, ‘Reset’ took the muddled thought process of a hangover).

I wouldn’t say I’m a naturally talented or intelligent person. That’s not false modesty, I have met naturally talented writers and they are not me – and that’s fine. I turn up and play the averages; if you keep writing and reading consistently, you have to produce something that resonates sooner or later. You just have to be prepared to put a lot of time and life into it. For every one poem I feel is successful, there are an inordinate amount of failures behind it with thirty or so hours spent on each. I kept my writing routine for over a period of nine-ish years and only thirty-six poems have made it into Slide. So, my process is glacial – it can feel like something akin to erosion.

You talked very entertainingly about mugging up on poetry (and the Eliot videos) lying in a bath filled with cushions. Would you say a bit more about which writers inspire you and why – what you look for?

MP: I miss that bathtub. It’s where I first read Liz Berry, Kei Miller, Sharon Olds, Tomas Tranströmer, Niall Campbell, Emily Berry and so so so many more excellent poets. I spent many a delicious morning in there feeling ‘physically as if the top of my head were taken off’ as Emily Dickinson famously said. Then I’d follow up by trying to puzzle out my own turns of phrase or staring at a YouTube video, of something like snow falling, trying to think of an interesting simile. It was a good writing desk and probably where I produced the first few poems I felt sounded more like me than my previous Armitage, Duffy and Robertson pastiches.

Which writers inspire me? So many. I could talk about any of the names I’ve mentioned above and many more: Alice Oswald, Fiona Benson, Don Paterson, John Burnside, Jean Sprackland, Michael Symmons Roberts, Kim Moore, Helen Mort, Andrew McMillan and on and on (if you are reading this and you are a poet just starting out, I could do a lot worse than recommend you read everything all the above poets have written).

However, the writer I always come back to – and anyone who’s shared a bottle of red with me has probably wished I’d shut up about – is Seamus Heaney. There are his images (that gorgeous ‘His shoulders globed like a full sail’, from ‘Follower’), his quietly earth-shattering voltas, turns and epiphanies (like the one from ‘Lightenings viii’), his economy of language (every single line in ‘Field of Vision’!). I could write reams – his sound textures, his formal control, his brutal honesty etc. Then there’s also the human being behind the poems – his stunning work ethic, how he reasoned that if poetry could be written in the trenches of the First World War, then it can be written anywhere. I particularly adore that one, it always gives me a good kick when I’m looking for an excuse not to write. He always seemed to me, in his writing and interviews, to be a deeply humble and unpretentious person – in a way I’ve never quite managed.

What touches me most, though, about Heaney’s work – especially after writing such a dark and (in places) hard to read book as Slide – are that so many of his poems feel so celebratory and life-affirming. Of course, he has written brilliantly and originally about loss, terror, violence and other more difficult subject matter. However, one day I would love to come close to such energising and powerful lines like those that round off what’s possibly my favourite poem every written, ‘Postscript’: ‘As big soft buffetings come at the car sideways / And catch the heart off guard and blow it open.’

Mark Pajak’s Slide is published by Cape Poetry. Watch the T. S. Eliot Prize filmed readings and interview, and read the reviews and Readers’ Notes online to find out more.

James Conor Patterson

James Conor Patterson is shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2022 for his debut collection, bandit country (Picador Poetry, 2022). We asked him about dialect and sense of place, politics, humour and liberation

T. S. Eliot Prize: Would you say something about Newry as a place and why it’s important to your book – as your home/the home you’ve left, its dialect, as an idea? ‘Bandit country’ is an old term isn’t it?

T. S. Eliot Prize: Would you say something about Newry as a place and why it’s important to your book – as your home/the home you’ve left, its dialect, as an idea? ‘Bandit country’ is an old term isn’t it?

James Conor Patterson: The impulse to write about Newry initially came from a desire to correct some of the more glaring misconceptions around my home, particularly in the wake of the Brexit vote in 2016. Settlements along the Irish Border suddenly found themselves in the unusual position of fulfilling tortured metaphors about the overall failure of the Brexit project, and newscasters were despatched on a near-weekly basis to warn their audiences about a potential ‘return to violence’ in a worst-case-scenario of border controls being implemented.

The Newry hinterland has a long history in this regard. In 1974, Labour-appointed Northern Ireland Secretary of State Merlyn Rees coined the term ‘Bandit Country’ to describe the South Armagh/South Down/North Louth border triangle, with the intention to stigmatise (and ultimately dehumanise) the local population. The British military had already committed atrocities in other Catholic areas of Northern Ireland – Derry’s Bogside, West Belfast’s Ballymurphy – and a certain level of plausible deniability was needed should something similar happen again. Civilians were therefore implicated in their own demise. Normal people became recalibrated as ‘bandits’, ‘rebels’, or to employ the less romantic terminology of Margaret Thatcher ‘criminals’, ‘terrorists’.

It was important, therefore, that bandit country reclaim the narrative of the area; not just by shifting focus away from the Troubles material readers have come to expect, but by rendering it in language that felt true to its inhabitants. A language as far removed from the received pronunciation and BBC English of the British State as it was feasible to use.

TSEP: In your Eliot Prize film interview, you talked about Joyce’s suggestion that if Dublin were suddenly to disappear it could be reconstructed out of Ulysses. Ciaran Carson – who was an important influence on you – had an interest in Belfast similar to Joyce’s in Dublin, but his idea was that a place could never be fixed. Have you couched the founding of Newry in ‘yew’ to signal that we are talking about an idea of a place, a phantasmagoria or myth as much as anyone’s reality?

JCP: The tension between Joyce’s idea and Carson’s idea is where bandit country ultimately lies, especially if we regard Joyce’s interest in Dublin as more personal than phenomenological and Carson’s interest in Belfast as somewhat more objective. In a sense, bandit country aims to convey both points of view, wherein my (the speaker’s) perception of Newry is necessarily shaped by lived experience.

In how this relates to ‘yew’, you’re right to suggest that when origin stories move beyond the control of their originator, they are often imbued with the personality of each new storyteller. In fact, much of Ireland’s folklore was passed along this way – through the oral tradition – and storytellers were often judged on how well they adapted or embellished a certain tale to suit the needs of their audience, or indeed, themselves.

TSEP: And yet… one of the big delights of bandit country is the powerful sense of place, its stories (some tall!), real incidents. Your use of dialect (as well as your punchy way with words and ideas) does some of that job. I’d love to hear you talk about northern Irish or Newry dialect. Had you an idea of it as a counterweight to the classical allusions in the collection, to Orpheus, the many descents?

JCP: I’m interested in Patrick Kavanagh’s notion that ‘Gods make their own importance’. That Newry – or anywhere for that matter – is as ripe for classical allusion as Thebes or Carthage or Alexandria. In ‘Epic’, the poem from which this line is taken, Kavanagh recounts a series of local squabbles in his native Monaghan, confesses that he is unsure of their significance (and thus the significance of his own life’s work), before ultimately concluding that literature and any richness of place ascribed it by its readers is only as strong as the poet making it: ‘Homer’s ghost came whispering to my mind. / He said: I made the Iliad from such / A local row.’

By rendering bandit country in language which is ‘local’, therefore, the book attempts to grasp at the universal, for what appeals to readers about stories like the Iliad is the idea that it could happen anywhere. One needn’t be adept in Hiberno-English to recognise that many of the scenarios in bandit country could play out just as easily in other environs. All it takes are some different street names, a new cast of characters, and some different inflections in how those characters speak.

TSEP: Can we ask about the tall stories? There are many dark, unsettling episodes but some are treated comically. Are they part of the cityscape or the landscape or in your head?

JCP: The tall tales in the book are inextricably linked to the landscape, and in many cases perform the action of landmarks more effectively than the physical characteristics of, say, buildings or streets, flora or fauna. In order to provide a sense of fixity when it comes to place – which, as we’ve seen in Ciaran Carson’s work, is difficult to achieve through physical description alone – it is necessary to populate it with the folklore, apocrypha, urban legend, and surreal gallows humour that makes it distinctive.

In Joan Didion’s 1979 essay collection The White Album, she writes that ‘we tell ourselves stories in order to live’ and in a certain sense this is true of what takes place in the book. The opposite is also true, with stories providing a kind of escapism from the psychological and physical damage wrought by long periods of conflict. The speakers in bandit country tell stories to one another in order to forget the drudgery of living; preferring instead to make sense of the world through ghost stories, tall tales, and tales of the macabre.

TSEP: ‘[P]hotographs, too, fulfilled this need / to anthologize and make tangible the fleeting…’ Would you talk about the photos in the book? What do they do (for you) as additions to the poems? Should poetry collections only include poems?

JCP: The photographs initially came from an impulse to set down visual cues (or prompts) for myself, which I could then write about. Later, I had the idea of using those photographs as companion pieces to the poems themselves, perhaps in an attempt to harken back to an earlier idea of what Irish writing looked like, where neither the text nor the image around it vied for supremacy, but would be taken together to form a cohesive whole, for example the glosses in The Book of Kells, the Cathach, The Book of the Dun Cow.

I was also inspired by the multimedia approach taken by modern writers like Caleb Femi and, in particular, Claudia Rankine who uses a combination of lyric, memoir and ‘found’ photographs to devastating effect in texts like Citizen, Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, and Just Us. Her work demonstrated to me that it was possible to write about multiple subjects within a given theme, whilst at the same time subtly employing the image to signal to the reader that a consistency underlies everything.

TSEP: There are many cycles that are difficult to escape in the book but it seems to me to steadily progress towards a sense of liberation. Is that right?

JCP: I think a book has to strive toward something in order to fulfil its promise. Whether ‘liberation’ is what bandit country strives toward I don’t know, though certainly ‘redemption’ plays its part. For me, the ultimate endpoint is ‘love’ in all its guises; whether that’s familial love, fraternal love, love for one’s community and culture, or simply the love and understanding of another like-minded individual – reader, partner, spouse – who shares in that redemptive journey.

James Conor Patterson’s bandit country is published by Picador Poetry. Watch the T. S. Eliot Prize filmed readings and interview, and read the reviews and Readers’ Notes online to find out more.

Denise Saul

The Room Between Us, says author Denise Saul, ‘can be viewed as an interrogation of chaos and order’, what happens when ‘the boundaries between “life and death”, “remembering and forgetting”, and “gain and loss” become blurry or porous’

T. S. Eliot Prize: One of the first poems in the book is ‘Stroke’, which is formatted as a dictionary entry and gives multiple definitions of the word: care, sudden even violent change, writing/language, repetition, water/landscape and time. This announces your key themes, doesn’t it?

Denise Saul: Yes. From the outset, the multiple definitions of ‘stroke’ define the various traumatic spaces in which writing/language and caregiving reside. As a carer, I started to question meanings of the term ‘stroke’ and how this medical condition links to other experiences of transformation and change.

TSEP: Your book is a deeply empathetic and moving exploration of how we communicate. Would you say something about communication in the context of aphasia, perhaps with reference to the work of the linguist Roman Jakobson, who you mention in our filmed interview.

DS: Jakobson’s essay, ‘Two Aspects of Language and Two Types of Aphasic Disturbances’, suggests aphasia is a ‘language disturbance’. For one type of aphasic disturbance, he uses the term ‘similarity disorder’, which refers to a major language deficiency that lies in word selection and substitution. My mother often produced elements of similarity disorder in her speech. Instead of saying the name of an object, sometimes she would substitute another word or rename that object. Some of the poems like ‘Clopidogrel’ reflect my mother’s experience of miscommunication. For example, the word ’cabbage’ might have started off as a phonologically related substitute but was replaced by a different word.

My mother also experienced ‘expressive aphasia’. Her speech and language therapist advised me to avoid asking open questions that invited more than a yes or no response. During conversations, I had to write down key words or draw diagrams and pictures. I often watched my mother’s thoughts unfold through gesture and speech.

TSEP: Some of your poems are prose poems and many are short, terse even – but they are much more than the sum of their concision. Can you say something about the different modes of language and your use of form?

DS: In TRBU I experimented with varied forms of the prose poem – like aphoristic, monologue and object-centred – to produce elements of aphasic embodiment or the carer’s narrative. This form destabilises the idea of freedom of space for the carer. Some poems sit within a condensed poetic form to mirror the breakdown of language and limited spaces experienced by the speaker. For other poems, the lyric form shapes the carer’s internal and external view of personal and public spaces. The forms used are mimetic of the emotional trauma experienced through miscommunication and the experience of caregiving.

TSEP: You talked about the domestic world of the cared-for and carer in our filmed interview. Would you like to say more about that, about the domestic space being both enclosed and permeable, even a site of revelation?

DS: Some poems locate my caregiving experience within the confinement or spaces of our house. Repetition of words like ‘window’, ‘room’ and ‘door’ situate the bodily experiences of caregiving and brain trauma in domestic spaces of confinement. The interplay between lines and the room-like form of some poems create new openings, unanswered questions and moments of doubt. The opening up of spaces within and around poems signals the rejection of closure.

TSEP: There seem to be parallel or dream worlds in poems such as ‘One’, ‘House of Blue’ or the very beautiful ‘Someone Walked Into A Garden’, which suggest a paracosm, a detailed imaginary world. Wikipedia says ‘paracosms function as a way of processing and understanding […] early loss’. But in your poems, these alternative or historical or mythical worlds seem a natural response of both the cared-for stroke survivor and the carer – an invented place in which they are able to meet and engage. Is that how you see it?

DS: Yes, I can connect to the idea of a paracosm. I wanted to give space to the caregiving experience. Writing this collection was never a linear process. This manifestation of ‘the parallel’ signifies the outer and inner worlds, that is, what is spoken and what is not. We expect a type of closure to occur at the end of reading The Room Between Us but that does not happen.

TSEP: Your repeated meditations on colour – how colours suggestively stand in for sense in non-conventional communication – is very powerful. Would you like to say something about that?

DS: TRBU meditates on the presence and absence of colour. My mother was a keen gardener so there is a natural affinity towards the representation of colour and light in nature as portrayed in the collection. The process of bereavement can heighten the bodily experiences like sound and sight. In moments of grief and trauma, our sense of seeing and hearing become intense or more vivid. In this collection, the colour spectrum allows various forms of grief to be fully experienced and expressed.

TSEP: In her blurb for your book, Nancy Campbell talks about ‘a fundamental enigma of human experience – how words bring order to the chaos of the cosmos’. That’s your theme, isn’t it?

DS: The book can be viewed as an interrogation of chaos and order. In moments of grief, there is also the moment when the act of remembering is questioned, and our sense of polarity comes under scrutiny. The boundaries between ‘life and death’, ‘remembering and forgetting’, and ‘gain and loss’ become blurry or porous.

Denise Saul’s The Room Between Us is published by Pavilion / Liverpool University Press. Watch the T. S. Eliot Prize filmed readings and interview, and read the reviews and Readers’ Notes online to find out more.

Yomi Ṣode

Yomi Ṣode is shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2022 for his debut collection, Manorism (Penguin Poetry, 2022). We asked him about its themes of identity, violence, masculinity, resistance and rest

T. S. Eliot Prize: ‘[P]rivilege, irrespective of time, allows a grace period’ (‘Fugitives’); ‘And who gets the pardon?’ (your postscript). Both these quotes link to Caravaggio, a key figure in Manorism. Can you say what your exploration of Caravaggio’s life and work yielded in terms of the inspiration behind your poems and Manorism more broadly?

Yomi Ṣode: I found Caravaggio while researching mannerist art of the sixteenth century. His work came just after that time period and I was struck by the story surrounding him, his work and his life.

Craft-wise, Caravaggio and I are not that far apart. I didn’t grow up with many male role models, our work is made through the lens of our communities, and our lives are not clean, easy or pretty.