2016

T. S. Eliot Prize

Winner

The Chair of the judges’ speech

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

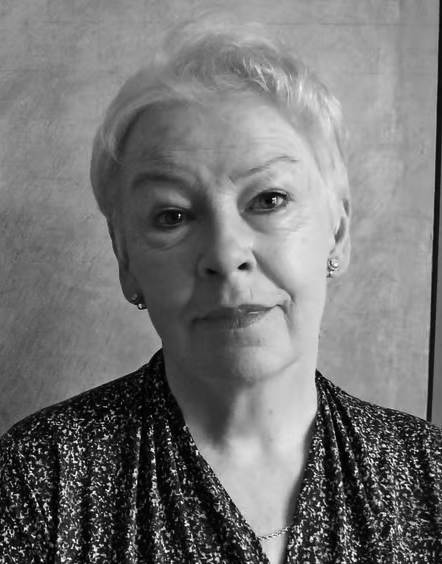

‘Many thanks to my fellow judges. We worked closely and harmoniously for six months and all of us enjoyed and felt enriched by each other’s views. The 138 collections we read testify to the rich variety of poetry published today and each of us gave up collections we really really wanted to agree to arrive at the Shortlist. We read each book purely for itself, so the list does not reflect the brilliant range of new poetry publishers, which we also want to applaud.’ – Ruth Padel, Chair

T. S. Eliot Prize 2016: the Chair of judges’ speech by Ruth Padel

Denise Riley’s unique contribution to contemporary poetry is her burningly fierce, lyric interrogation of the language – and philosophy – of self. Say Something Back is full of anger but also humour, prayer, a ballad-like beauty and audacious metrical control. From the death of the poet’s child to the dead of the First World War it asks a question that matters to us all. Faced with human tragedy, what on earth is poetry for? But it also provides an answer. What we have here, sufficient to itself and in wonderfully beautiful variety, is song.

Ruby Robinson’s Every Little Sound, from the wonderful new Pavilion Poetry at Liverpool University Press, takes off from the concept of ‘internal gain’: an ‘inner volume control’ which helps us focus, especially in time of danger, on important sound which may be hard to hear but really quiet. Like poetry, perhaps. In this sparky debut, the language is brilliantly hyper-perceptive. Through a range of forms and tones, these disturbing, surreal, deceptively conversational poems cunningly hunt out what we listen for with our ‘nerve endings in exile’.

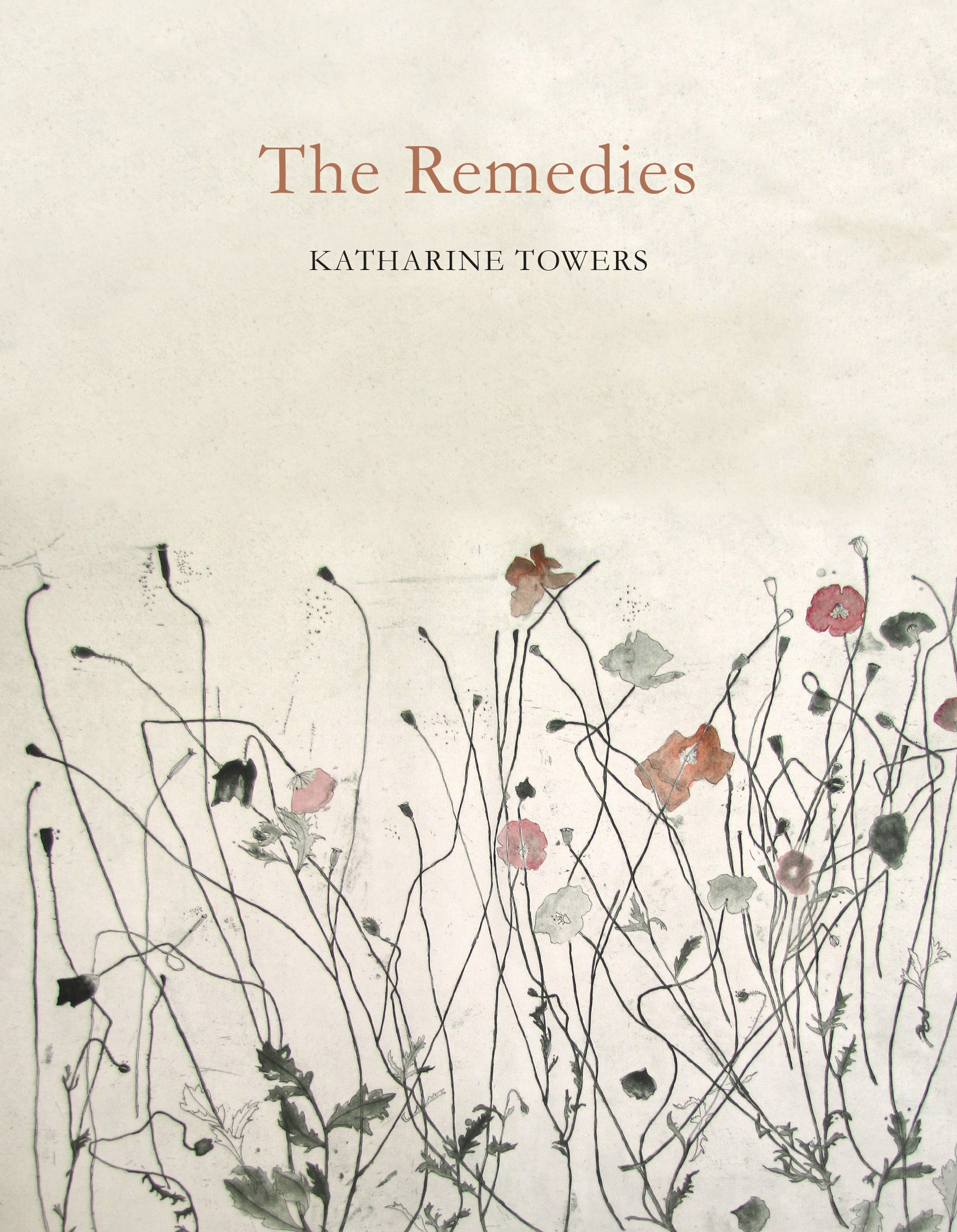

Heartrendingly beautiful is easy to say, hard to do, but the poems in Katherine Towers’s The Remedies are just that. This collection, full of linguistic delights, turns on our relation with nature. Nature is not ‘about us’ and yet we read ourselves into it all the time. These petal-light poems – like, in their own words, bones of trees laid bare by the moon – distil the paradox of poetry: that something so small, so delicate, has such enormous spiritual and emotional power.

It was an agonising choice. They are so different and all so wonderful. I never want to have to choose anything again. But the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2016 is Jacob Polley for Jackself.

This speech was given at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2016 Award Ceremony at the Wallace Collection, London, on 16 January 2017.

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘Many thanks to my fellow judges. We worked closely and harmoniously for six months and all of us enjoyed and felt enriched by each other’s views. The 138 collections we read testify to the rich variety of poetry published today and each of us gave up collections we really really wanted to agree to arrive at the Shortlist. We read each book purely for itself, so the list does not reflect the brilliant range of new poetry publishers, which we also want to applaud.’ – Ruth Padel, Chair

T. S. Eliot Prize 2016: the Chair of judges’ speech by Ruth Padel

Denise Riley’s unique contribution to contemporary poetry is her burningly fierce, lyric interrogation of the language – and philosophy – of self. Say Something Back is full of anger but also humour, prayer, a ballad-like beauty and audacious metrical control. From the death of the poet’s child to the dead of the First World War it asks a question that matters to us all. Faced with human tragedy, what on earth is poetry for? But it also provides an answer. What we have here, sufficient to itself and in wonderfully beautiful variety, is song.

Ruby Robinson’s Every Little Sound, from the wonderful new Pavilion Poetry at Liverpool University Press, takes off from the concept of ‘internal gain’: an ‘inner volume control’ which helps us focus, especially in time of danger, on important sound which may be hard to hear but really quiet. Like poetry, perhaps. In this sparky debut, the language is brilliantly hyper-perceptive. Through a range of forms and tones, these disturbing, surreal, deceptively conversational poems cunningly hunt out what we listen for with our ‘nerve endings in exile’.

Heartrendingly beautiful is easy to say, hard to do, but the poems in Katherine Towers’s The Remedies are just that. This collection, full of linguistic delights, turns on our relation with nature. Nature is not ‘about us’ and yet we read ourselves into it all the time. These petal-light poems – like, in their own words, bones of trees laid bare by the moon – distil the paradox of poetry: that something so small, so delicate, has such enormous spiritual and emotional power.

It was an agonising choice. They are so different and all so wonderful. I never want to have to choose anything again. But the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2016 is Jacob Polley for Jackself.

This speech was given at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2016 Award Ceremony at the Wallace Collection, London, on 16 January 2017.