Times are dark, but the poets are singing. 2019 has been another strong year for poetry. Thematically, poetry is increasingly, necessarily political. Brecht asked in 1938:

What kind of times are they, when

A talk about trees is almost a crime

Because it implies silence about so many horrors?

We live in an age where the default collection from the end of the last century, with its poems about uncomplicated landscapes or small, personal epiphanies, would feel equally uncomfortable. Who can write about a tree now without acknowledging ecocide? Who can write about their holiday without thinking of privilege, borders, carbon footprints? Paul Farley’s The Mizzy channels John Clare, but even a small poem about a goldcrest ends with us caught in the ‘simple trap’ of money.

It is also apparent that collections containing long sequences are dominating lists. Just a few years ago I was chatting to other editors about the increasing irrelevancy of the standard 64-page collection, now that readers can share so many individual poems online, and cheap, attractive pamphlets are easy to produce. But collections seem relevant again, having reinvented themselves as cohesive sequences in which poets can go more deeply into their subject. Whilst Philip Larkin treated collections: ‘like a music-hall bill: you know, contrast, difference in length, the comic, the Irish tenor, bring on the girls’, many books on this year’s Shortlist give the reader an experience more akin to a novella.

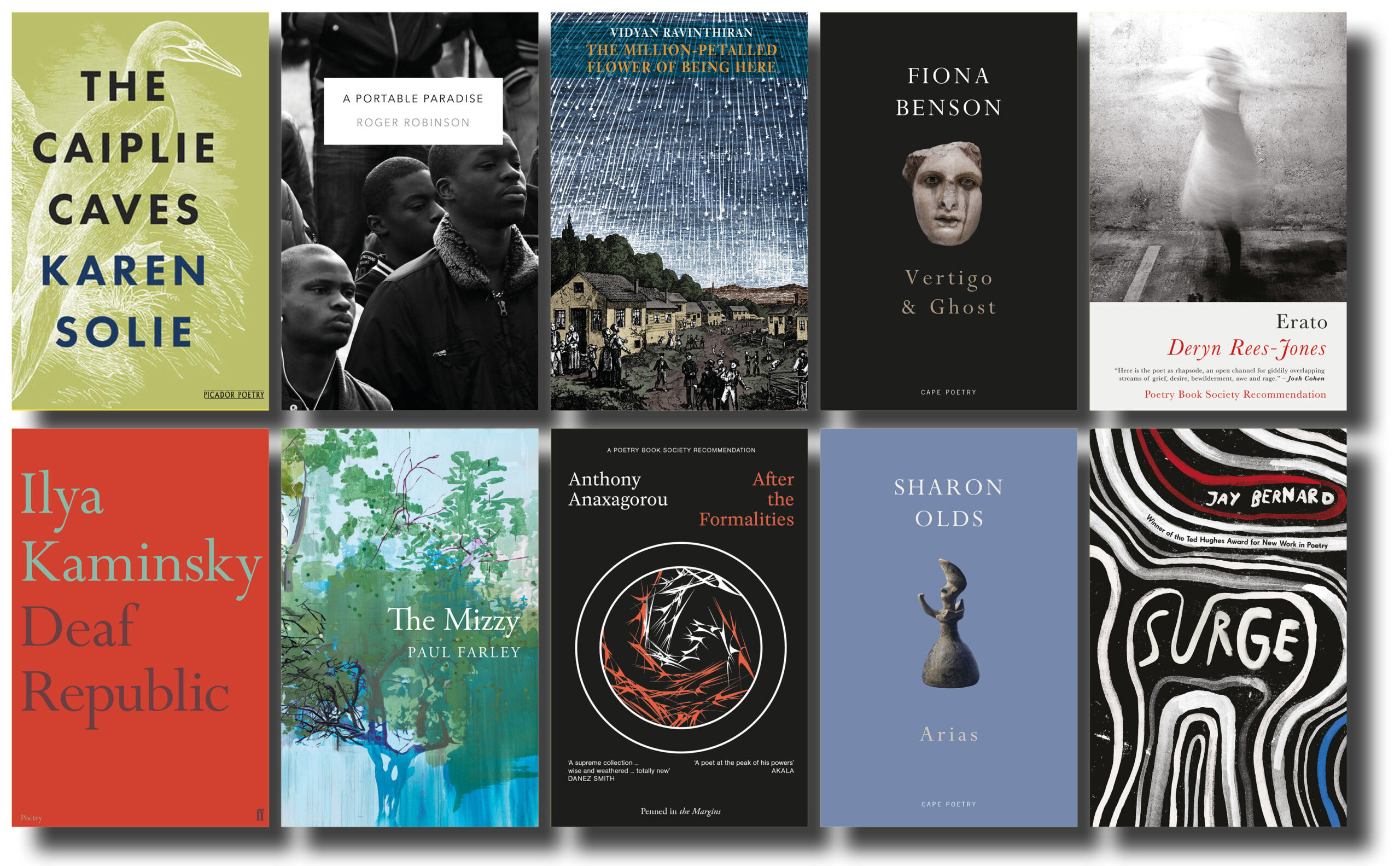

In Karen Solie’s The Caiplie Caves the relationship between humanity and nature is explored through the ghost of a seventh-century hermit called Ethernan; Fiona Benson’s taut sequence figures Zeus as a serial-rapist; Vidyan Ravinthiran’s The Million-petalled Flower of Being Here contains a generous sonnet-cycle that explores love and race in Brexit Britain; Jay Bernard’s Surge traces links through black history between the New Cross Fire in 1981 and the Grenfell tragedy; whilst Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic is a fable about resistance and silence. In very different ways each absolutely captures our political moment.

This year has also reminded us that whilst increased diversity amongst emerging poets is being celebrated, we must also lift up existing poets who have been underrated, or who have worked hard clearing the way. It’s wonderful to see Roger Robinson (and Peepal Tree) finally getting some of the attention deserved in the UK for his powerful collection A Portable Paradise.

It’s also pleasing to see Deryn Rees-Jones on the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist, a poet who has built such a strong female list at Pavilion, along with Anthony Anaxagorou, founder of Out-Spoken Press, which aims to challenge the lack of diversity in British publishing. Not to mention Sharon Olds, who was writing trailblazing motherhood poems when the current wave of poets writing about motherhood were still in nappies (and, elsewhere, the poetry world was thrilled to see Bernardine Evaristo, founder of the Brunel International African Poetry Prize and The Complete Works, win the Booker!)

So, a year for shoring up our strengths and singing in the dark, though sometimes it must be admitted that, for this reader at least, the surfeit of talent feels almost too lucky. In Kaminsky’s words: ‘we (forgive us) // lived happily during the war.’

Clare Pollard is a poet and editor of Modern Poetry in Translation, and was a judge of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2018. Visit Clare Pollard’s website.