T. S. Eliot Prize News

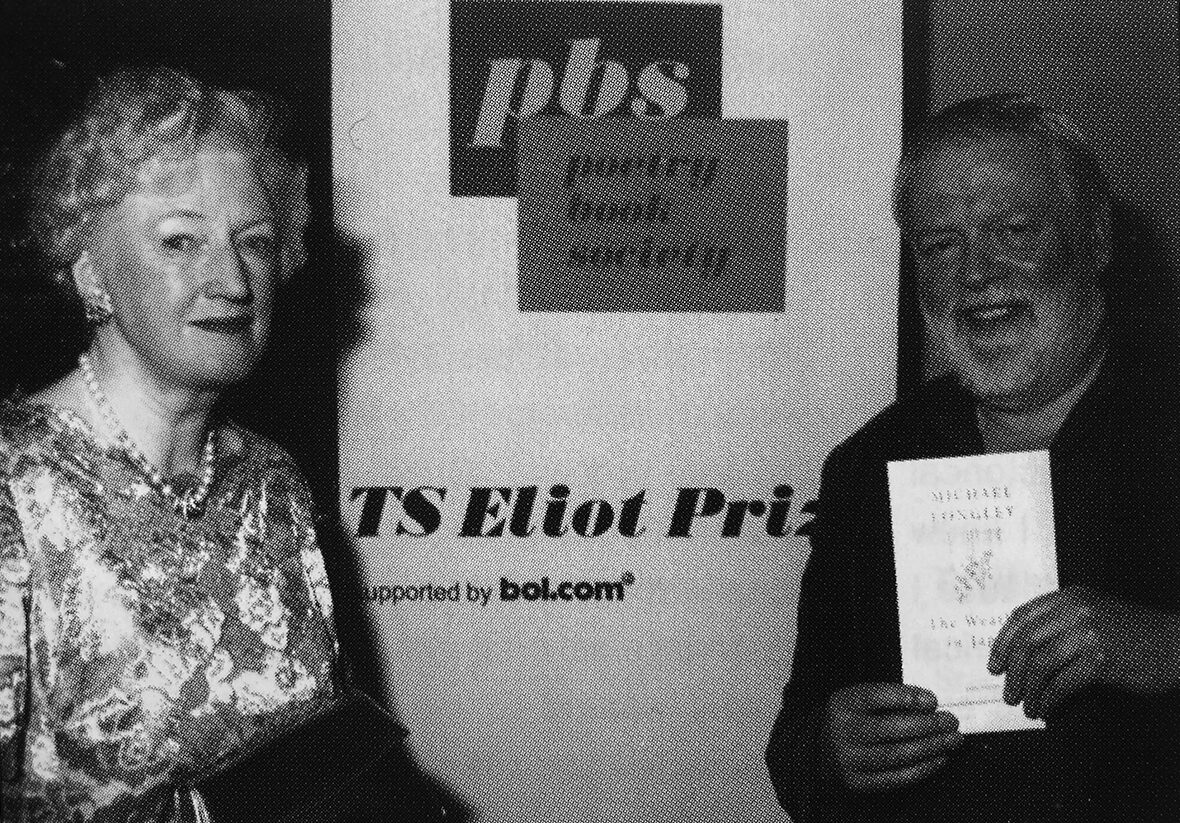

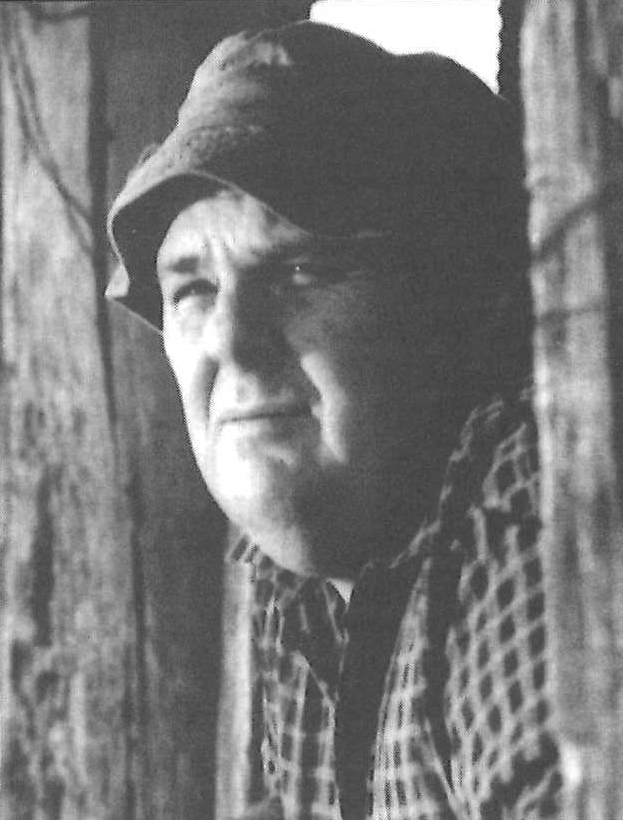

This article on the early years of the T. S. Eliot Prize was written and added to the website in 2025. The winner of T. S. Eliot Prize 2000 was Michael Longley for his collection The Weather in Japan (Cape Poetry). Longley was presented with a cheque for £10,000,...

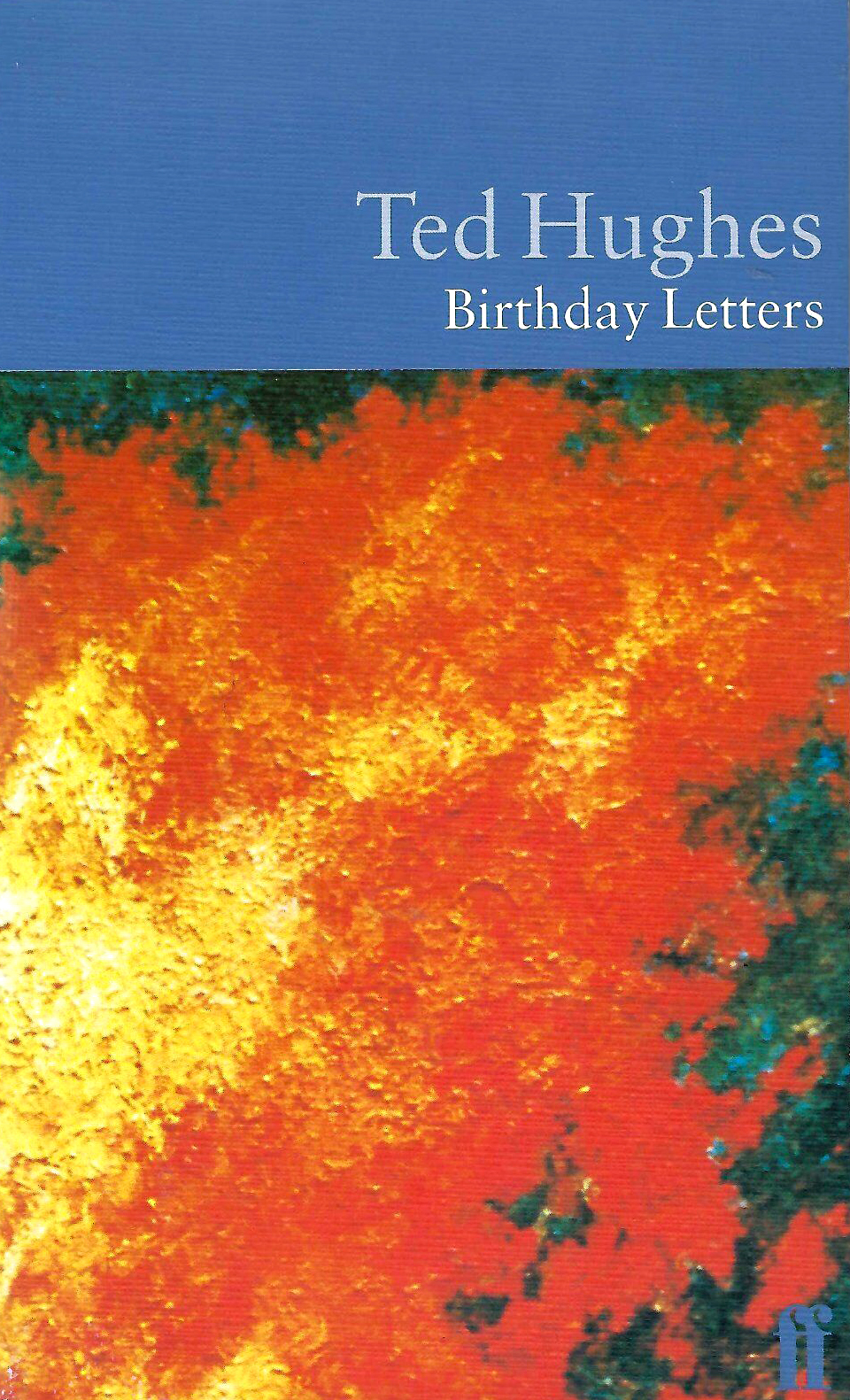

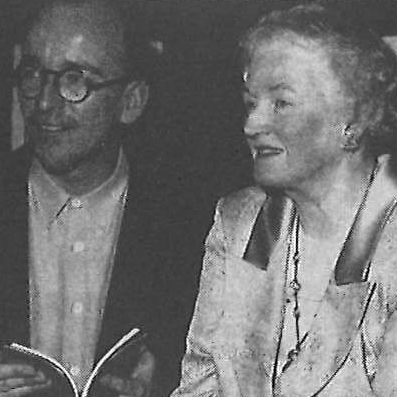

This article on the early years of the T. S. Eliot Prize was written and added to the website in 2025. The winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 1998 was Ted Hughes for his collection Birthday Letters (Faber & Faber). The prize was awarded posthumously, Ted Hughes having...

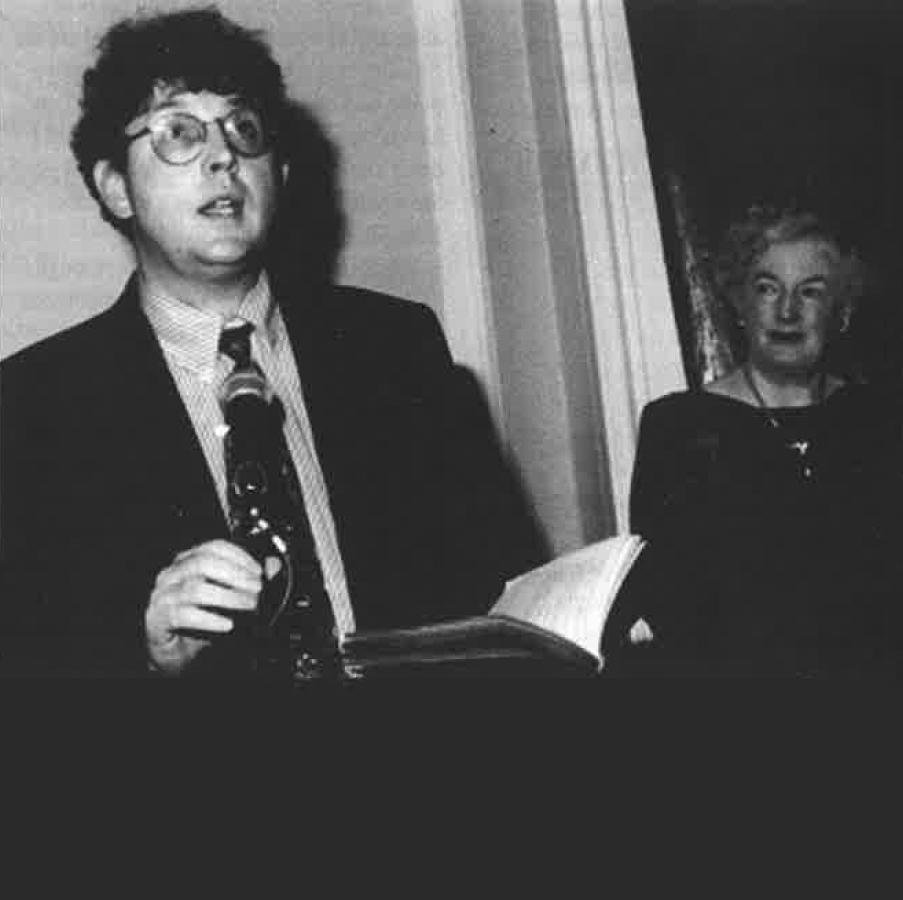

This article on the early years of the T. S. Eliot Prize was written and added to the website in 2025. The winner of T. S. Eliot Prize 1997 was Don Paterson for his collection God’s Gift to Women (Faber & Faber). He was presented with the £5,000 prize,...

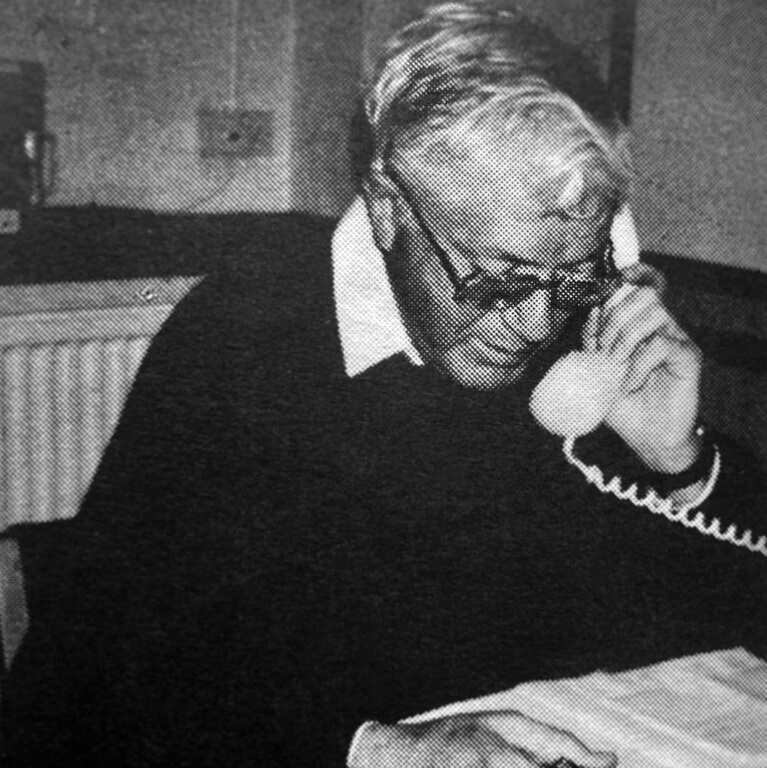

This article on the early years of the T. S. Eliot Prize was written and added to the website in 2025. The winner of T. S. Eliot Prize 1993 was Ciaran Carson for his collection First Language, published by the Gallery Press. He was awarded £5,000, the generous gift...