This article on the T. S. Eliot Prize was first published on the Poetry Book Society website in 2014.

It would have been marvellous to detect in the air around now a rising hum of argument and speculation about the shortlist for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2014. In a better world, it would have been building up gradually from an intelligent interest in new volumes of verse created over the months by critics of different persuasions, writing – with the encouragement of enlightened literary editors – in all the major newspapers and journals. But what a remote hope all that has become!

As we all know, media interest in poetry, when it turns up at all, arrives mostly in the shape of uninformed prejudice, while poetry reviewing in the books pages – which could produce a climate of appreciative attention for poetry – is, with rare exceptions, either reduced, or crowded out by editorial capitulation, even in the once-heavyweight ‘serious’ journals, to the priority of bestselling popular titles.

Why are there are no successors in the dailies, or the weeklies on Fridays or Sundays, or in some substantial literary monthlies, to the committed and hardworking reviewing regulars of the recent past? I am thinking of the likes of A Alvarez, Ian Hamilton, Martin Dodsworth, Pete Porter, John Mole, all of whom had columns in which to cover half-a-dozen slim volumes of verse every few weeks, keeping readers in the picture, winning gratitude and respect – though sometimes also a degree of fear – from poets and their publishers?

The answer is that some excellent critical dragons for today could be found among a rising generation of readers and critics if only editors took the trouble, and had the courage and conviction, to go and look for them – and give them the column inches for round-ups of new poetry. Some of the conviction would, of course, have to be shared by fairly senior persons in the news media, figures with authority in places where the content and tone of cultural coverage is determined. But poetry is an art which often has a gripping private significance for people. Some powerful and unlikely persons have been known secretly to read it, respond to it, and even write it; so applying a bit of persuasion about its current range and variety and its continuing importance could still work in some cases.

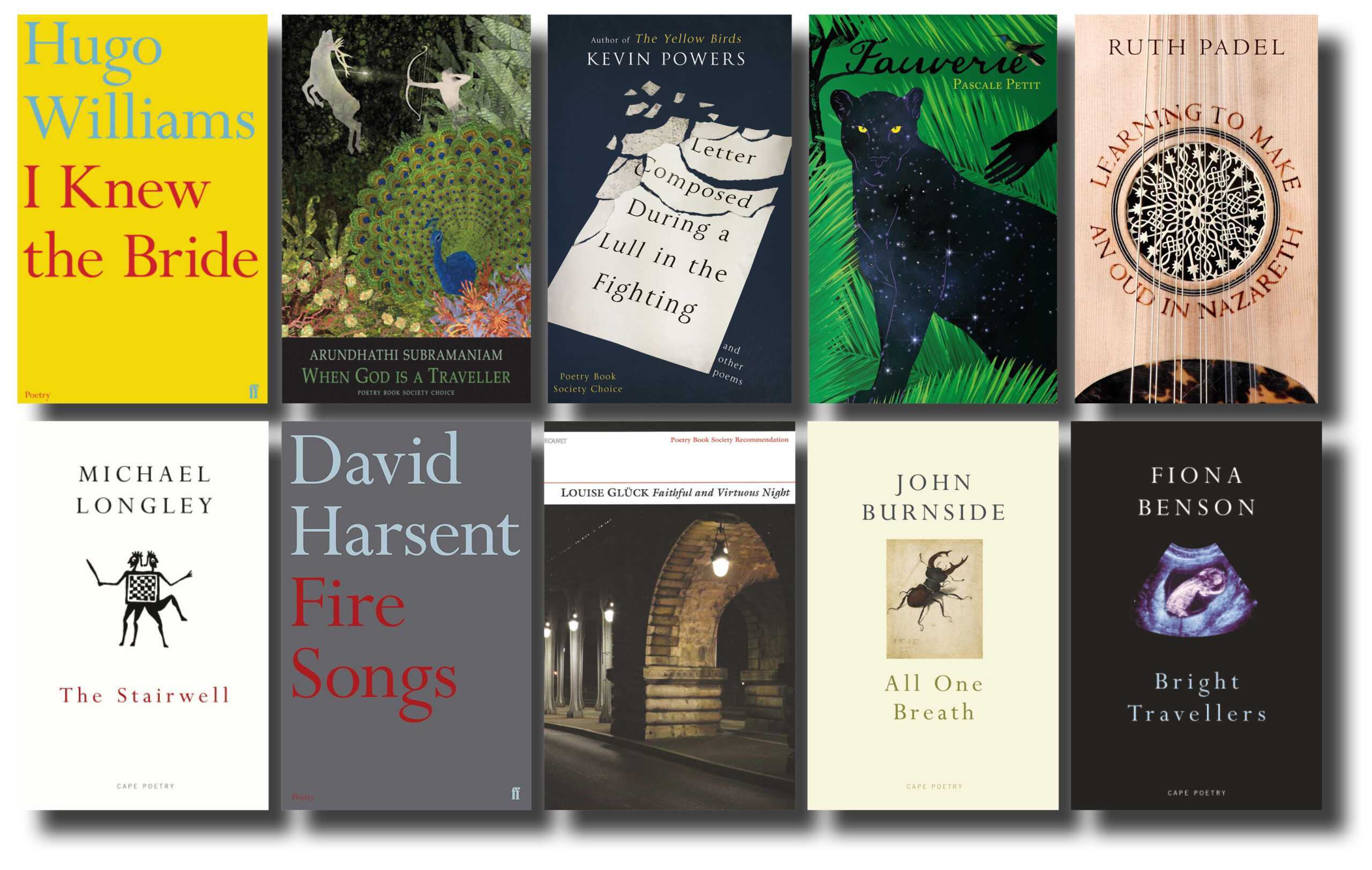

The judges for the T. S. Eliot Prize are required to include in their shortlist of ten books the four quarterly Choices made by the two selectors for the Poetry Book Society (PBS) during the year: in 2014 these are collections by John Burnside, Kevin Powers, Michael Longley and Arundhathi Subramaniam. For the remaining six it is open to them to choose from the entire range of volumes of a suitable length published in the United Kingdom in 2014, the Recommendations of the PBS selectors being strong contenders.

This year four recommended books (by Hugo Williams, Fiona Benson, Louise Gluck and David Harsent) have made it to the last ten and the final two, ‘outsiders’ or ‘wild cards’ if you like – though neither is a stranger to award shortlisting – are new volumes by Ruth Padel and Pascale Petit. All ten books have just landed on the mat of this writer at the same time, so I will do what I can to be useful or controversial for PBS members, or for anyone not a member who should be and who happens to go to the Society’s website. And for the judges, naturally.

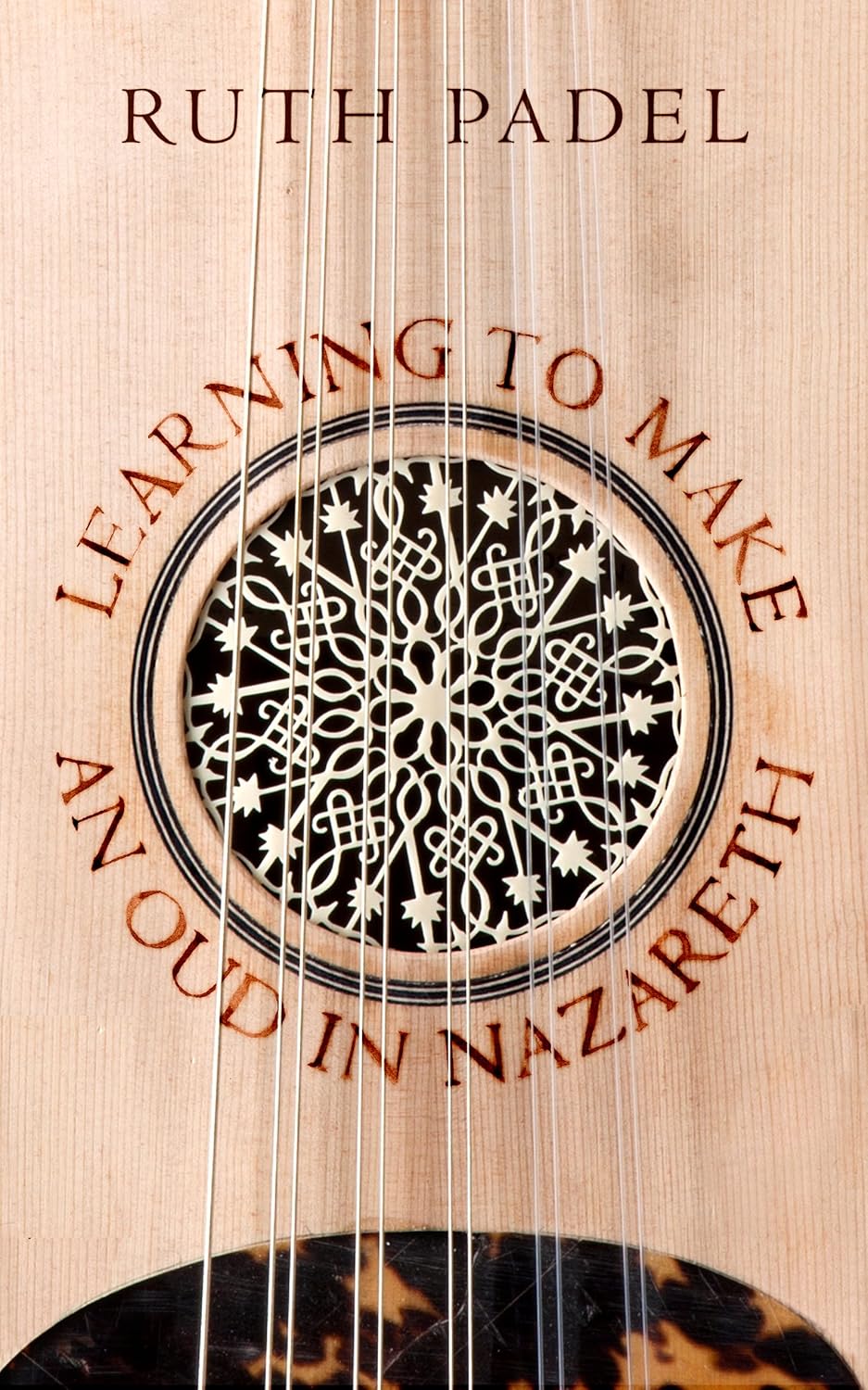

Padel’s Learning to Make an Oud in Nazareth (Chatto & Windus, £10.00) leaves me admiring the purpose – these being offered, no less, as poems that aim to ‘address the Middle East’ – but uncertain of the achievement. A balance in the representation of cultures would have been impossible, as would any adequate account of present-day life, and death, in the region. In fact what we have is a number of shorter pieces (on Arab and Jewish themes and a few subjects not related to the middle East at all) preceding and following two longer Christian poems: an uncomfortable assemblage. The title piece, about the oud, ‘the central instrument of Middle Eastern music’ (common to all cultures) reads in places like a faithful translation:

I have found him whom my soul loves.

He inlaid the sound-hole with ivory swans,

each pair a valentine of entangled necks…

which, like the rest of this poem, is agreeable, even touching; but nothing in the same style and mood accompanies it in the book. The two best poems, to which Padel’s readers will surely wish to return, need not have been here: ‘Pieter the Funny One’, about Bruegel the Elder (who painted a Flight into Egypt – there’s a link for you), and ‘Birds on the Western Front’: ‘the lark in early dawn/ singing fit to burst but coming over insincere/ above plough-land latticed like folds of brain// with shell-ravines where nothing stirs/ but rats, jittery sentries and the lice/ sliding across your faces every night.’

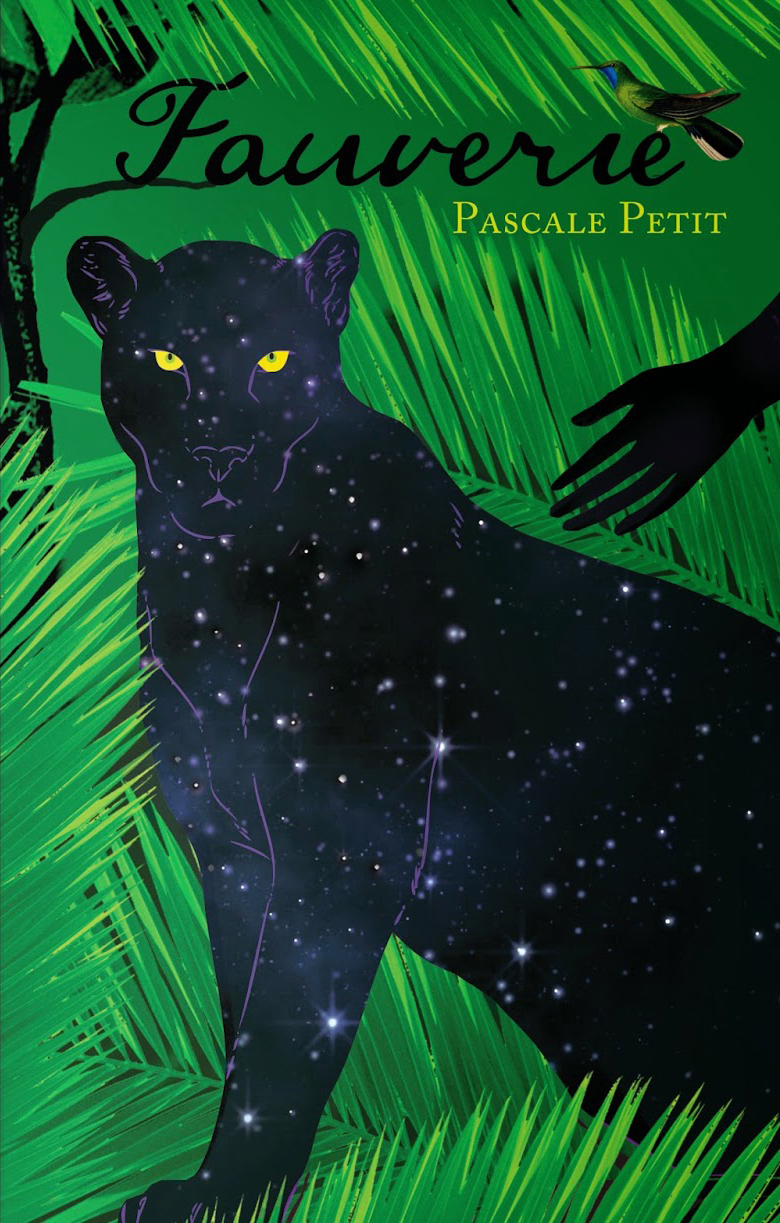

Fauverie (Seren, £9.99), Pascale Petit’s sixth collection, returns to the themes which she has made her own since The Zoo Father: the colourful ferocity of the animal kingdom as seen in the wild or in captivity, Paris (her birthplace and favourite city), and her relationship with the eponymous parent of that volume, a matter of much pain. Describing a favourite kind of subject for her, butchery counters (in ‘Grenelle Market III’), she writes of spending ‘what seemed like a whole night in the cellar’ and of finding how, ‘as coins / passed back and forth, my memory of the dark / vied with my appetite for colour.’

Petit’s is not the grimmest poetry book of the shortlisted ten (I shall be coming to David Harsent’s Fire Songs) but the darkness in her many scrupulous accounts of her father’s illness and death is deep. The peace which comes ‘after bloodshed’ in the moment of final reconciliation which ends Fauverie, has only been anticipated in a small number of calmer pieces like ‘Hand’, and ‘My Father’s City’: ‘…when // car horns and sirens fail to wake you / and the doctor comes to switch off your oxygen, / I see you stretched out on your narrow bed/ like an etiolated city, O my father, all your gates closed.’ Such endings are genuinely moving.

Fire Songs (Faber & Faber, £12.99) is formally the most accomplished book on the list — new readers might look first at the handling of dream imagery with all its appealing strangeness (never an easy task) in the finely controlled rhyming stanzas of ‘A Dream Book’. But if that is one of the gentler poems here, it is still a disquieting piece in a collection of unremitting harshness which has the PBS selectors, who gave it a Recommendation, oddly invoking ‘transforming fire’ (my italics) ‘righteous judgement’ and ‘just witness’. Those qualities might be matters for debate to which the poet himself might be entitled to contribute.

But what is clear is that David Harsent has acquired his impressive formal expertise painfully and given us here, in turn, sequences of powerful, rigorously crafted and distressing poems on the violent uses of fire (for execution, as nuclear holocaust, or in the destruction of a lifetime’s papers), on the ineradicability of rats, and the personal affliction of tinnitus. ‘Pain’ sums it up: ‘Pain in birdsong, pain in rough weather, pain in the sound of the sea, the air thick with contagion, windborne, isobars of the fever-chart, skim on rivers, spoilage and spillage, gutter-run…’ A book for readers appreciating grim subject-matter and formal expertise, but not one for the squeamish.

The selectors made a Choice and a Recommendation of two first collections in summer 2014. The American writer Kevin Powers was already known for a bestselling first novel, The Yellow Birds; Letter Composed During a Lull in the Fighting (Sceptre, £12.99) and continues in poetry that book’s theme of war experience in Iraq in the mid-2000s, though with something more of the impact on family and community (in ‘A History of Yards’ or ‘Church Hill’).

The war is still close for Powers as serviceman and writer, and familiar – at least at secondhand – to those who followed it with fear and pain through the images and the language promoted by the media. So the first question is bound to be, What can poetry add to all of that; and a supplementary question: Is it too soon to say? With some of the early work here I find I am wondering whether Powers is far enough away from the rhetoric — and damagingly, the more dramatic kind of prose poem reportage – that went with the conflict?

A poem like ‘Improvised Explosive Device’ brings the reader up to date with some brutal realities of terrorist warfare, and yet – ‘this poem / does not come with an instruction manual. These words / do not tell you how to handle them’ …Is this poetry, or just a knowing turn of phrase? With later pieces like ‘The Abhorrence of Coincidence’ or ‘Songs in Planck Time’ (with its surprising final twist), Powers is establishing a more individual, and surer, voice and rhythm. His second and third books could be worth waiting for.

‘Still there is unslaked thirst in the higher cells / as water burns from leaves like shallow pans / and the chaffy head erupts in flames. // Dear one, I listen to you move in the other room / and I burn…’ Fiona Benson is paying passionate tribute to Vincent Van Gogh’s ‘Sunflowers’ in one of several sequences of poems in Bright Travellers (Cape Poetry, £10.00) – other sets venture into the history of the Devon she has made her home, describe the bitter loss involved in miscarriage, rejoice in the birth of her daughter.

Meticulous, if small-scale, observation of nature – it’s intriguing to find how often poets still return to that – is one of her strengths, but the Van Gogh poems do most to ‘cram her book with light’, as she wishes. They are done with considerable spirit, each representing a different painting, as a curious kind of welcome to an uninvited guest (or more; a companion on the road to Emmaus, as another poem hints?) and produce a desirable balance between grief and celebration in a very promising debut collection.

At first sight the short, slender, unrhymed poems in Arundhathi Subramaniam’s When God is a Traveller (Bloodaxe Books, £9.95) may seem informal and casual, pieces about love, place, work, the perils of friendship, etc. – offering agreeable wisdoms which vanish when you turn the page. But if that is an unfair judgement her publishers’ claim that they ‘explore…the persistent trope of the existential journey’ doesn’t do her much of a service.

A lesser, though still important, claim would be more reasonable: the poems are often acute, sly and funny and her (not-so-gentle) satire can be unexpectedly effective. She is adept in giving advice to the young (‘Eight Poems for Shakuntala’) and devising ‘Quick-fix Memos for Difficult Days’; and scary about ‘Living with Earthquakes’: ‘…this glass elevator // plummeting // past picknicking families, / Pomeranians in suburban gardens, / sturdy investment bankers, /vaporising faces, names losing their voltage…’

Faithful and Virtuous Night is the long title of the latest book by Louise Gluck, an award-winning American poet published for some time by the best smaller publishers here but still perhaps lacking the critical recognition she deserves. For £9.95, Carcanet produce this volume on broad pages which handsomely accommodate her long lines; and her extended title-poem sets the style and mood. If there is a recurrent fault in the poems it’s in a rather too relaxed and casual approach to intriguing, sometimes very touching, themes, mostly concerned with childhood, family, place and time – one would have to listen to the argument that some are in prose.

Is it enough for an important poem just to stop: ‘I think here I will leave you. It has come to seem / There is no perfect ending. / Indeed, there are infinite endings. / Or perhaps, once one begins, / there are only endings.’ Some eerie prose poems (‘The Open Window’, ‘The Couple in the Park’ – with its nod towards Verlaine) work as well as the verse. There are ample compensations in the shock of surprise that often arrives in her treatment of ordinary moments: passing city monuments on an excursion, ‘we moved into the future / while experiencing perpetual recurrences’; and dust on old photographs becomes ‘the persistent / haze of nostalgia that protects all relics of childhood.’

And so to three former prizewinners, all of whom could be firmly ruled in with their new collections. In All One Breath (Cape, £10.00), his fourteenth book, John Burnside begins with a stern sequence of poems on mirrors, including a hall of ‘infinite reflection’ in a fairground, his grandmother’s mirrors, a ‘Spiegelkabinett’ in Berlin and his own mirrors at home. This presents, with characteristic lyric range and intensity, some original takes on a much-visited subject.

‘Devotio Moderna’, his shorter second section, is a group of meditations on graver topics; for example, hoping at New Year to brighten fate ‘with something more inventive than dismay.’ In fact, where that is achieved most in All One Breath is in the two later sequences, ‘Life Class’ and ‘Natural History’. In the first of those the use of a controlled narrative structure in ‘The Day Etta Died’, ‘The Vanishing of my Sister, Aged 3’ and ‘Travelling South’ results in some of the finest poems of a personal kind that Burnside has ever produced. In ‘Natural History’ his ‘Sticklebacks’ and ‘Peregrines’ similarly rank among his best in that category. Yet the odd one out, his gentle tribute to the poet Dennis O’Driscoll, who died in 2012 – it’s a tribute to the art of poetry also – is the most moving:

Say what you will, all making is nostalgia,

hurrying back to name the things we missed

the first time, when the world seemed commonplace…

In his last two or three volumes Michael Longley has, if anything, deepened his lifelong devotion to craft and care in poetry. The Stairwell (Cape Poetry, £10.00) returns to concerns we might expect from him: classical legends and lessons we can still enjoy and learn from; family, with several new poems for his grandchildren and twenty-three poignant ones in memory of his recently dead twin brother; tender — or bitter — memories; and celebrations of beloved home-from-home places in the rural Ulster he escapes to from West Belfast. He brings together the numerous short poems and those different themes here in a kind of elegiac unity.

Longley is hardly ever a rhyming poet, but almost any Longley sentence may be read for the weight he invests in an individual line — with its initial capital letter affirming that it cannot be heard merely as part of a prose argument. Who else currently writing actually listens to the lines and judges length and stress so carefully while composing them? Take the beautifully-judged, easy-sounding sonnet about his father and Ronald Colman, who met during the Great War — a rueful memory:

He watched him trimming his moustache in cold tea

At a cracked mirror, a thin black line his trademark.

Wounded at Messines — shrapnel in his ankle –

He tried in his films to cover up his limp — Beau

Geste, Lost Horizon – my Dad would go to see them all.

Did he share a lastWoodbine with Ronald Colman

Standing on the firestep, about to go their separate

Ways over the top, into No Man’s Land, and fame?

If form is important to Michael Longley, taking a risk by being completely honest and candid is essential to Hugo Williams. There used to be something known as ‘confessional’ poetry, which presupposed the poet in question had some high personal drama or tragedy to be confessional about. Williams realised as long ago as his volume called Dear Room that moment-to-moment living in familiar surroundings has quirks and illogicalities that can morph into terrors enough – and being straightforward about those can be both absorbing and alarming. Nowadays he finds that experience of dialysis is not going to be transmuted by an ‘abstract expressionist’ approach but only confronted outright, in all its ‘ghastly literalness.’

I Knew the Bride (Faber & Faber, £12.99) contains his full sequence ‘From the Dialysis Ward’, with its raw medical detail and ironic conclusions: ‘The beauty of dialysis / is that it saves you the trouble / of planning too far ahead, or working out what you’re going to do / with your afternoons. / It uses up half your life / without your lifting a finger.’

And yet this is, even without that, a substantial and wide-ranging collection, featuring also a set of ‘lost-love’ poems ‘Now that I’ve Forgotten Brighton’ (the message being that he hasn’t: ‘Perhaps if I lie still / watching the tops of trees / scratching low clouds / I won’t remember / her bedside manner, / her sense of etiquette.’), freestanding poems about childhood, school, home (surviving the stairs) and bereavement. The title-poem, about the illness and death of his sister, is deeply moving because of its very plainness and Williams’ resistance to any temptation to embellish.

This is a book to return to, for many reasons – perhaps even in the end finding out what is actually going on in that cryptic little item called ‘The Chinese Stock Exchange’.

PBS members will have had the opportunity to read the four Choices on the shortlist, and may have gone on to take in some of the sixteen Recommendations. Quite rightly, given the number and variety of poetry books published each year, ten is more than appear on some other well-known shortlists, I suppose because poetry volumes are famously slimmer (and mostly cheaper) than some other books. It wouldn’t be too hard, would it (I have done so) to read them all between now and the day in January when the judges meet in the afternoon and arrive at a verdict announced that evening?

I don’t wish to encourage rivalry between prize awards, but readers who do that would not only have a comprehensive picture of what is now happening in poetry but a better one than the knowledge of current fiction gained by investing in a smaller batch of novels?

Alan Brownjohn has published twelve individual volumes of poetry, three collected editions, and five novels. The Saner Places: Selected Poems came out in 2010. From 1990 to 2012 he was a regular poetry critic of the Sunday Times with Sean O’Brien.

This article has been republished to provide a fuller picture of the T. S. Eliot Prize history. The Poetry Book Society ran the T. S. Eliot Prize until 2016, when the T. S. Eliot Foundation took over the Prize, the estate having supported it since its inception.