2014

T. S. Eliot Prize

Winner

The Chair of the judges’ speech

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘Fire Songs by David Harsent asks what is the worst that human beings can do to one another, and how can there be resistance? They are timely questions. ‘Fire: a song for Mistress Askew’ opens the collection. Here, Harsent goes as close as he can to the flames that consumed the poet and Protestant martyr Ann Askew in 1546. He probes the nature of ‘knowing’ both as intimacy and as factual, historical knowledge. The sombre, intricate music of these poems plumbs language and emotion, in the awareness that there is no bottom. We are aghast at the spirit that tortured Anne Askew, and yet we live in its world; we turn away from the fire and it licks after us. These are beautiful poems for dark and dangerous days.’ – Helen Dunmore, Chair

I’d like to talk about the ten shortlisted collections in alphabetical order.

Fiona Benson‘s first collection, Bright Travellers, is strikingly intense in tone and economical in language. The surface is taut, the emotion vivid but never sprawling. She writes of pain, transience, the passion of the moment and the understanding that this falls away even as it is experienced; she draws on myth with supple energy. Her poems of miscarriage, birth and motherhood are as fearless as they are beautiful. It would be impertinent to call Fiona Benson a poet of promise when so much here is eloquently fulfilled, but much as her poems achieve, they suggest that more is possible for this gifted poet.

The poems in John Burnside’s All One Breath are profoundly spiritual while marvellously homed in the everyday. He writes about mortality and the agony of expulsion from innocence – if, indeed, innocence has ever been a home. Burnside is poet of the ‘life perpetual’, ceaselessly renewing itself in every living thing, rather than the ‘life eternal’, and he is also the poet as outsider. Indeed, he is the laureate of self-castigation. John Burnside’s wonderfully bold, even ecstatic use of language shines through the collection. He is memorable with apparent effortlessness and his metaphor falls into place as if it could never have been otherwise.

In Faithful and Virtuous Night, Louise Glück pegs out a narrative, an apparent history of a child suddenly orphaned and left to the care of an aunt. The narrative is fragmented and shown from many angles; Glück plays to and with the reader’s overwhelming desire to create a story which makes sense; but she also frustrates this and forces the reader back on her own resources. Is this how the past really looks? Is this how it should be looked at? Glück’s plain diction and slightly dreamy, almost surreal tone give these poems an entrancing quality. They engage the mind; they ask questions which have to be answered within the reader, because the text offers no short cuts.

Fire Songs by David Harsent asks what is the worst that human beings can do to one another, and how can there be resistance? They are timely questions. ‘Fire: a song for Mistress Askew’ opens the collection. Here, Harsent goes as close as he can to the flames that consumed the poet and Protestant martyr Ann Askew in 1546. He probes the nature of ‘knowing’ both as intimacy and as factual, historical knowledge. The sombre, intricate music of these poems plumbs language and emotion, in the awareness that there is no bottom. We are aghast at the spirit that tortured Anne Askew, and yet we live in its world; we turn away from the fire and it licks after us. These are beautiful poems for dark and dangerous days.

In Michael Longley’s The Stairwell there are finely wrought poems of love and loss, of grandchildren and the abandonment of regret; of a brother’s death and a father’s memory; of funeral music and the experiences of a young Irishman at the Somme. In this collection there are elegies but also poems that greet and celebrate new life, written with great tenderness and power, and a certain wry knowingness about the pretensions of the self and others. Longley’s poems are a joy for their immaculate judgment of tone and their passionate, laconic conjurings of the natural world. His poems rest on the page like driftwood, seasoned and made beautiful by an ocean of experience.

Like David Harsent, Ruth Padel comes close to the horrors humans inflict on themselves and others. Her poem ‘Seven Words and an Earthquake’ is a meditation on the seven last words of Christ and a meditation on the sufferings of all who fail to please those in power:

‘Handcuffed

You found others to care about. The guard who whacked you in the mouth for keeping silent under questioning; squaddies

expert in the flay, who sliced off your back and shoulders; the centurion with digital timer who posed by your naked body. Anything goes

at the checkpoint, the cell, the interview room.’

For Padel, cruelty and oppression is the work of all who allow it, or who benefit from it. Making an Oud in Nazareth reveals her fine intellect, sensuous detail and passionate musicality.

The animals of the Fauverie in Paris – Aramis the black jaguar first among them – pad through Pascale Petit‘s new collection, as charismatic as the father whose magnetism still holds the narrator transfixed after many years of estrangement. The voice of Fauverie speaks both bravely and with bravura from the heart of its material. There is conspiracy in these poems and great beauty. They venture into the cellar of the past, summon up memory and conjure it into a firework display of metaphoric brilliance. Pascale Petit, in the tradition of Ted Hughes or indeed T. S. Eliot, understands that through knowing the nature of beasts we come to know ourselves.

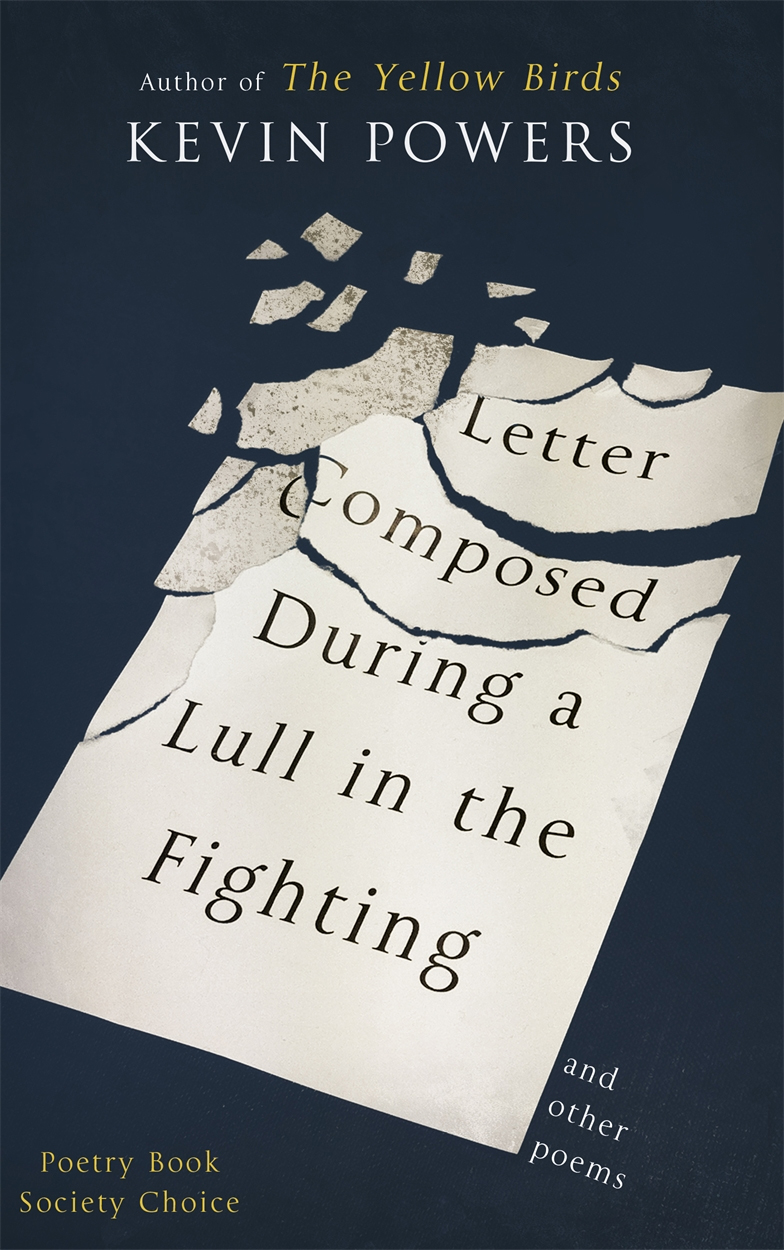

The squaddies ‘expert in the flay’ are viewed from outside in Ruth Padel’s ‘Seven Words and an Earthquake’, but in Kevin Powers‘ collection Letter Composed During a Lull in the Fighting the soldier is the insider, the describing voice, the flayed personality. Powers writes this sequence about his tour of duty in Iraq in 2004/2005, which he has also described in his novel The Yellow Birds. The poet works from that place of war and from within the claustrophobia of a return to a home which is no longer home. The poems question language and landmarks in a struggle to establish stable meaning, and they ask what the world expects of soldiers, as it delegates to them its violence, expediency and desires.

In Arundhathi Subramanian’s When God is a Traveller, it is myth, seasoned by generations of ancestors, which travels into the present moment on its journey towards the future. How do we receive and understand the shaping myths of our culture? How can we understand the full resonance of poetry which draws on those myths for its being, if we don’t share them?

‘Nothing original

but the hope

of something new

between parted lips.’

Lips part to breathe, and breath is the essence of poetry as well as of life. These four short lines show how Subramaniam pares down her poetry, weighs it, subtracts everything from it but resonance. She also questions the idea that novelty is what we should be seeking. Why should the new be privileged over a deeper understanding, or re-interpretation, of what has gone before?

The defining quality of Hugo Williams‘ new collection, I Knew the Bride, is, in Hemingway’s words, grace under pressure. Very rarely is there such lightness of form and tone in poems which deal with grief, loss, sickness, pain, death. Williams never talks about such things – he simply puts them down, complete, in a few lines so poised and deft that immediately it’s clear they could never have been written otherwise. I could talk about the trenchancy, wit and glancing perception with which he writes about dialysis – or the beautiful elegy for a little sister – but far more remarkable is his gift for creating poems which make you want to linger within them, and to return to them again and again.

This speech was given by Helen Dunmore at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2014 Ceremony at the Wallace Collection, London, on Monday 12 January 2015.

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘Fire Songs by David Harsent asks what is the worst that human beings can do to one another, and how can there be resistance? They are timely questions. ‘Fire: a song for Mistress Askew’ opens the collection. Here, Harsent goes as close as he can to the flames that consumed the poet and Protestant martyr Ann Askew in 1546. He probes the nature of ‘knowing’ both as intimacy and as factual, historical knowledge. The sombre, intricate music of these poems plumbs language and emotion, in the awareness that there is no bottom. We are aghast at the spirit that tortured Anne Askew, and yet we live in its world; we turn away from the fire and it licks after us. These are beautiful poems for dark and dangerous days.’ – Helen Dunmore, Chair

I’d like to talk about the ten shortlisted collections in alphabetical order.

Fiona Benson‘s first collection, Bright Travellers, is strikingly intense in tone and economical in language. The surface is taut, the emotion vivid but never sprawling. She writes of pain, transience, the passion of the moment and the understanding that this falls away even as it is experienced; she draws on myth with supple energy. Her poems of miscarriage, birth and motherhood are as fearless as they are beautiful. It would be impertinent to call Fiona Benson a poet of promise when so much here is eloquently fulfilled, but much as her poems achieve, they suggest that more is possible for this gifted poet.

The poems in John Burnside’s All One Breath are profoundly spiritual while marvellously homed in the everyday. He writes about mortality and the agony of expulsion from innocence – if, indeed, innocence has ever been a home. Burnside is poet of the ‘life perpetual’, ceaselessly renewing itself in every living thing, rather than the ‘life eternal’, and he is also the poet as outsider. Indeed, he is the laureate of self-castigation. John Burnside’s wonderfully bold, even ecstatic use of language shines through the collection. He is memorable with apparent effortlessness and his metaphor falls into place as if it could never have been otherwise.

In Faithful and Virtuous Night, Louise Glück pegs out a narrative, an apparent history of a child suddenly orphaned and left to the care of an aunt. The narrative is fragmented and shown from many angles; Glück plays to and with the reader’s overwhelming desire to create a story which makes sense; but she also frustrates this and forces the reader back on her own resources. Is this how the past really looks? Is this how it should be looked at? Glück’s plain diction and slightly dreamy, almost surreal tone give these poems an entrancing quality. They engage the mind; they ask questions which have to be answered within the reader, because the text offers no short cuts.

Fire Songs by David Harsent asks what is the worst that human beings can do to one another, and how can there be resistance? They are timely questions. ‘Fire: a song for Mistress Askew’ opens the collection. Here, Harsent goes as close as he can to the flames that consumed the poet and Protestant martyr Ann Askew in 1546. He probes the nature of ‘knowing’ both as intimacy and as factual, historical knowledge. The sombre, intricate music of these poems plumbs language and emotion, in the awareness that there is no bottom. We are aghast at the spirit that tortured Anne Askew, and yet we live in its world; we turn away from the fire and it licks after us. These are beautiful poems for dark and dangerous days.

In Michael Longley’s The Stairwell there are finely wrought poems of love and loss, of grandchildren and the abandonment of regret; of a brother’s death and a father’s memory; of funeral music and the experiences of a young Irishman at the Somme. In this collection there are elegies but also poems that greet and celebrate new life, written with great tenderness and power, and a certain wry knowingness about the pretensions of the self and others. Longley’s poems are a joy for their immaculate judgment of tone and their passionate, laconic conjurings of the natural world. His poems rest on the page like driftwood, seasoned and made beautiful by an ocean of experience.

Like David Harsent, Ruth Padel comes close to the horrors humans inflict on themselves and others. Her poem ‘Seven Words and an Earthquake’ is a meditation on the seven last words of Christ and a meditation on the sufferings of all who fail to please those in power:

‘Handcuffed

You found others to care about. The guard who whacked you in the mouth for keeping silent under questioning; squaddies

expert in the flay, who sliced off your back and shoulders; the centurion with digital timer who posed by your naked body. Anything goes

at the checkpoint, the cell, the interview room.’

For Padel, cruelty and oppression is the work of all who allow it, or who benefit from it. Making an Oud in Nazareth reveals her fine intellect, sensuous detail and passionate musicality.

The animals of the Fauverie in Paris – Aramis the black jaguar first among them – pad through Pascale Petit‘s new collection, as charismatic as the father whose magnetism still holds the narrator transfixed after many years of estrangement. The voice of Fauverie speaks both bravely and with bravura from the heart of its material. There is conspiracy in these poems and great beauty. They venture into the cellar of the past, summon up memory and conjure it into a firework display of metaphoric brilliance. Pascale Petit, in the tradition of Ted Hughes or indeed T. S. Eliot, understands that through knowing the nature of beasts we come to know ourselves.

The squaddies ‘expert in the flay’ are viewed from outside in Ruth Padel’s ‘Seven Words and an Earthquake’, but in Kevin Powers‘ collection Letter Composed During a Lull in the Fighting the soldier is the insider, the describing voice, the flayed personality. Powers writes this sequence about his tour of duty in Iraq in 2004/2005, which he has also described in his novel The Yellow Birds. The poet works from that place of war and from within the claustrophobia of a return to a home which is no longer home. The poems question language and landmarks in a struggle to establish stable meaning, and they ask what the world expects of soldiers, as it delegates to them its violence, expediency and desires.

In Arundhathi Subramanian’s When God is a Traveller, it is myth, seasoned by generations of ancestors, which travels into the present moment on its journey towards the future. How do we receive and understand the shaping myths of our culture? How can we understand the full resonance of poetry which draws on those myths for its being, if we don’t share them?

‘Nothing original

but the hope

of something new

between parted lips.’

Lips part to breathe, and breath is the essence of poetry as well as of life. These four short lines show how Subramaniam pares down her poetry, weighs it, subtracts everything from it but resonance. She also questions the idea that novelty is what we should be seeking. Why should the new be privileged over a deeper understanding, or re-interpretation, of what has gone before?

The defining quality of Hugo Williams‘ new collection, I Knew the Bride, is, in Hemingway’s words, grace under pressure. Very rarely is there such lightness of form and tone in poems which deal with grief, loss, sickness, pain, death. Williams never talks about such things – he simply puts them down, complete, in a few lines so poised and deft that immediately it’s clear they could never have been written otherwise. I could talk about the trenchancy, wit and glancing perception with which he writes about dialysis – or the beautiful elegy for a little sister – but far more remarkable is his gift for creating poems which make you want to linger within them, and to return to them again and again.

This speech was given by Helen Dunmore at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2014 Ceremony at the Wallace Collection, London, on Monday 12 January 2015.