1993

T. S. Eliot Prize

Winner

The Chair of the judges’ speech

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

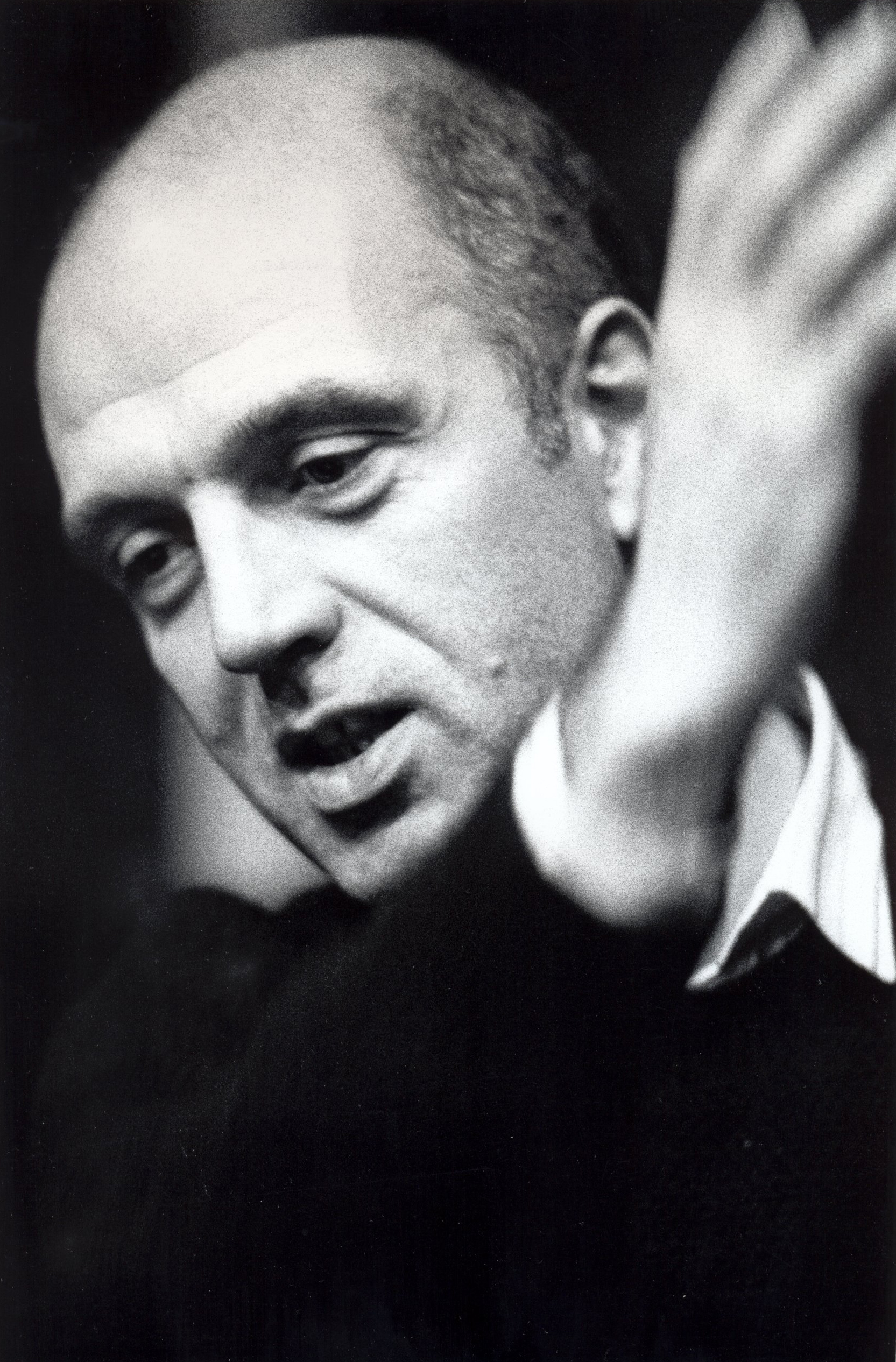

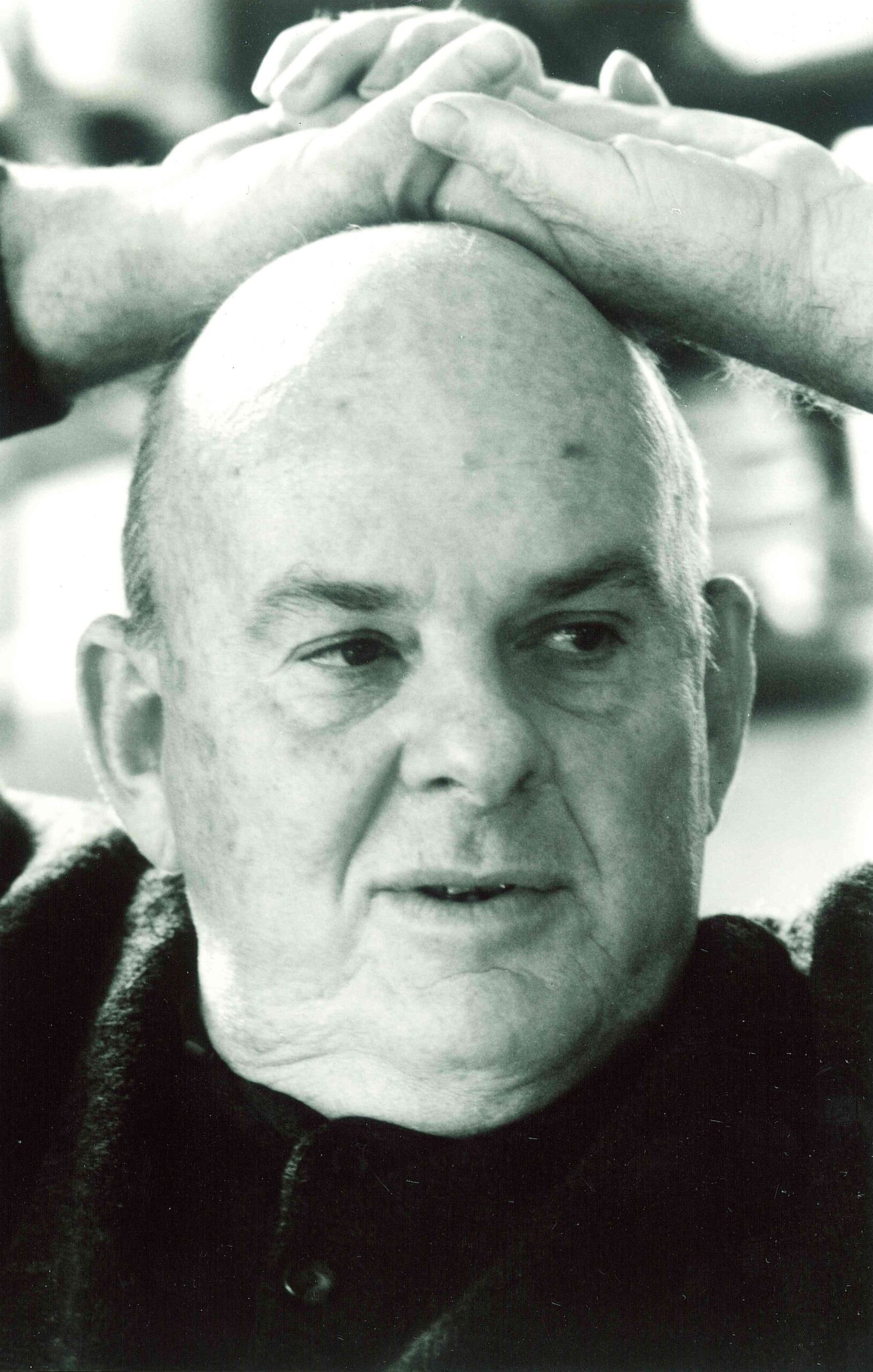

‘Whether or not poetry is doing well at the moment will go on being debated. In my experience poetry is always on the point of becoming popular: we are always on the threshold of a poetry boom. But it is natural that we should be concerned with our immediate present. After all, this is poetry you don’t need to footnote.’ – Peter Porter, Chair

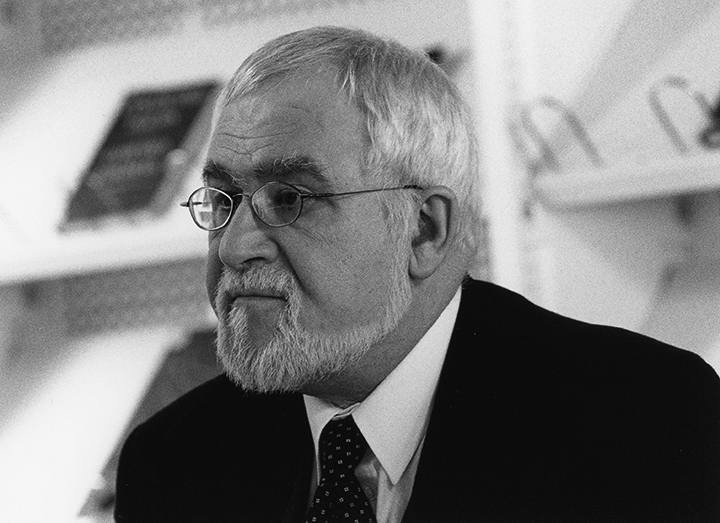

The Anatomy of a Prize – Peter Porter, Chairman of the judging panel, on the inaugural T. S. Eliot Prize of 1993

There are two very different views of poetry in its own time. In the first, Philip Larkin stresses that the present is always overrated. The second, espoused by the great poet whose name distinguishes this prize, is that we cannot appreciate the past and its achievements if we cease to care for the present. It isn’t that we use the past as insemination of the present (or not only that) but that we will cease to be able to understand the past unless we keep faith with the present.

We are here tonight to honour the second view – T. S. Eliot’s view. Whether or not poetry is doing well at the moment will go on being debated. In my experience poetry is always on the point of becoming popular: we are always on the threshold of a poetry boom. But it is natural that we should be concerned with our immediate present. After all, this is poetry you don’t need to footnote.

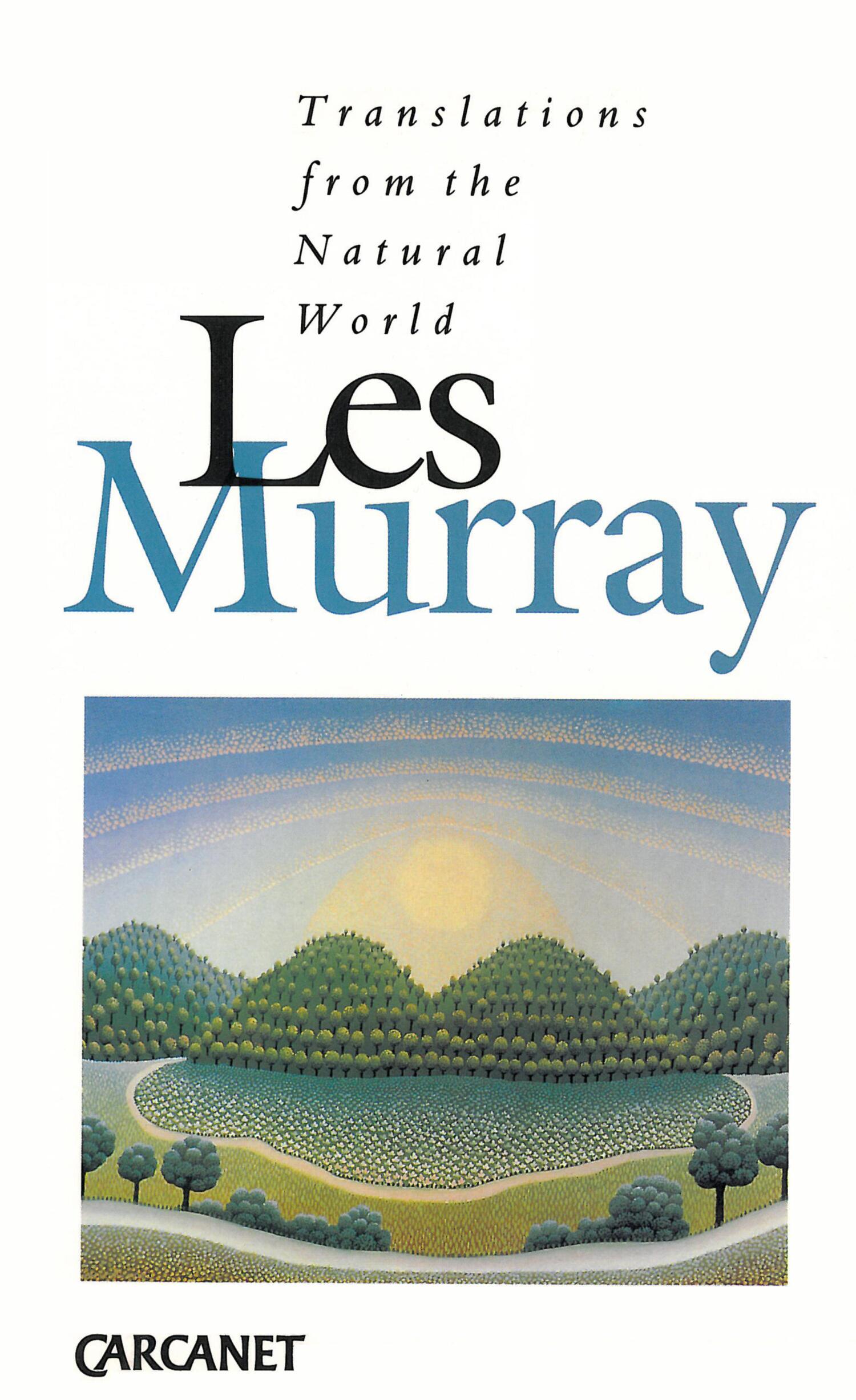

The Eliot Prize is not concerned with generations, or geographical or ethnic considerations. It simply aims to pick the best original book of poems in English published in Great Britain during the past year. To that end, we, the judges, read more than 100 volumes. We were made to work hard by the sheer high quality of the work we examined. We neither wanted nor were able to be parti pris. To this end, I’d remind you of statements by two of the poets shortlisted. Firstly, Les Murray, who has remarked of the readership of poetry in English, ‘We’re Country and Western.’ Secondly, James Fenton, who writes, ‘This is no time for people who say: this, this and only this. We say: this and this and that too.’ We ended up with the conviction that poetry is in good health today. If it is held by many to be irrelevant to matters of contemporary living, it remains as central as ever to the mystery of language.

In 1759 Christopher Smart wrote ‘For the English tongue shall be the language of the West.’ Admittedly he was mad at the time and confined to Bedlam. But his prophecy has come to pass. Consider the shortlist of our poets and the composition of our judging panel. They come from the compass points of both hemispheres. The judges hail from England, Scotland, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand. The poets from the same spread of place except that the United States is substituted for New Zealand. English speakers have developed into several nations of poets.

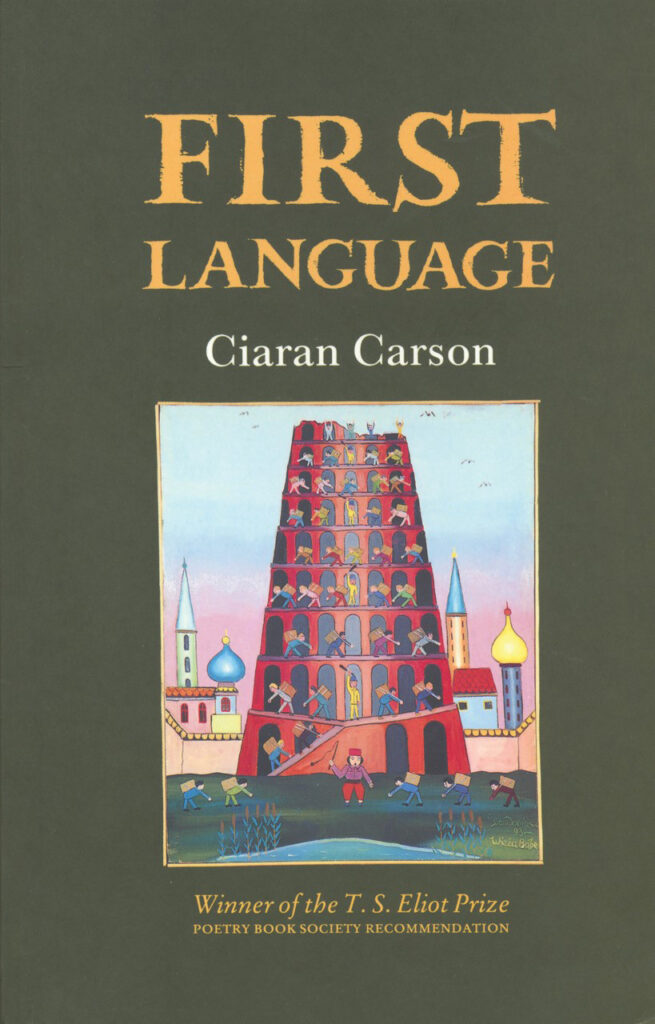

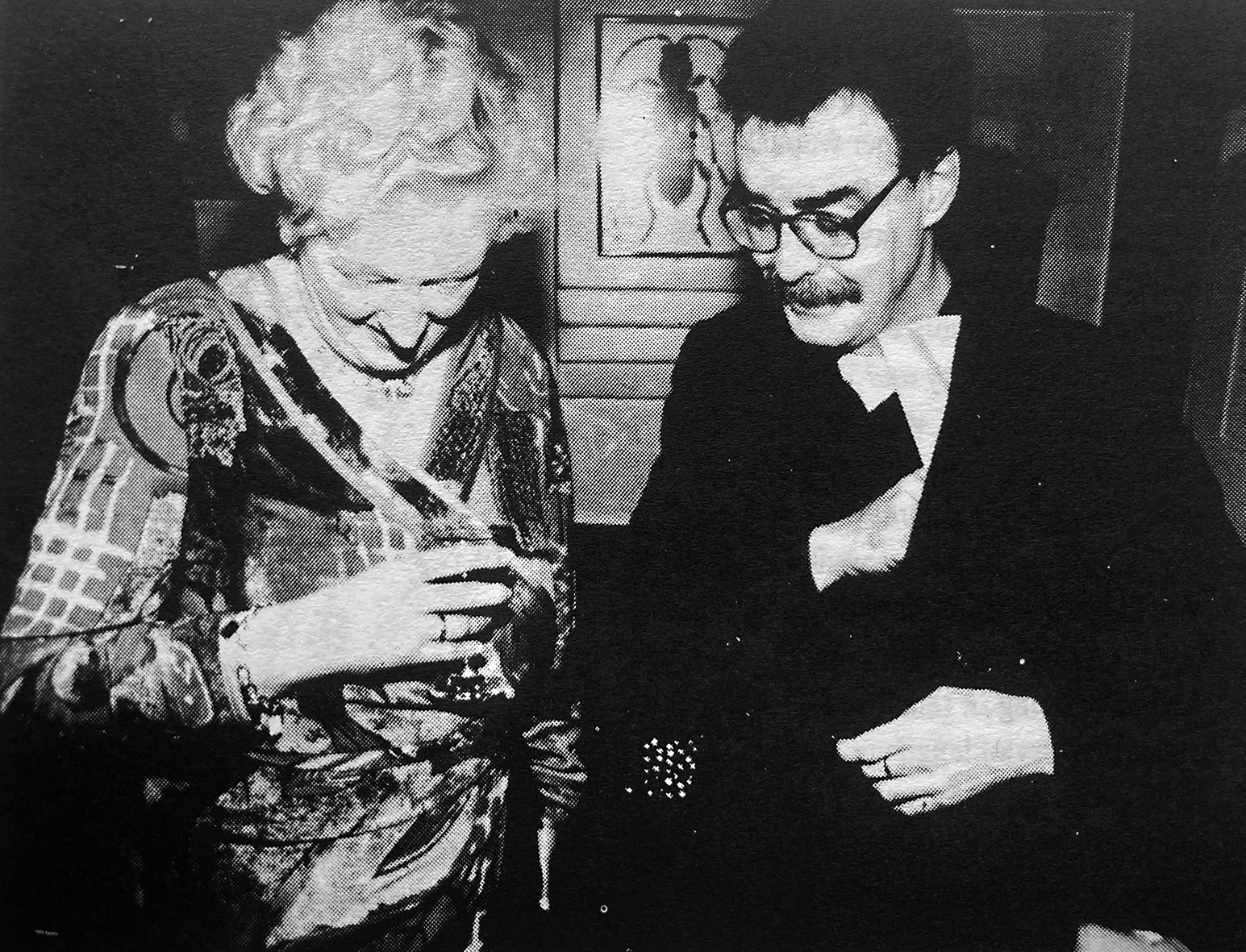

This is not the time or place to go through the many talents and gifts of our ten shortlisted poets. It was hard enough for the judges to come to a decision, without now looking out the markings. The input made by the members’ vote was taken fully into account. The argument was long and exhausting, but will now be instantly resolved. The winner of the first T. S. Eliot Prize for the best original book of poetry published in the UK in 1993 is Ciaran Carson.

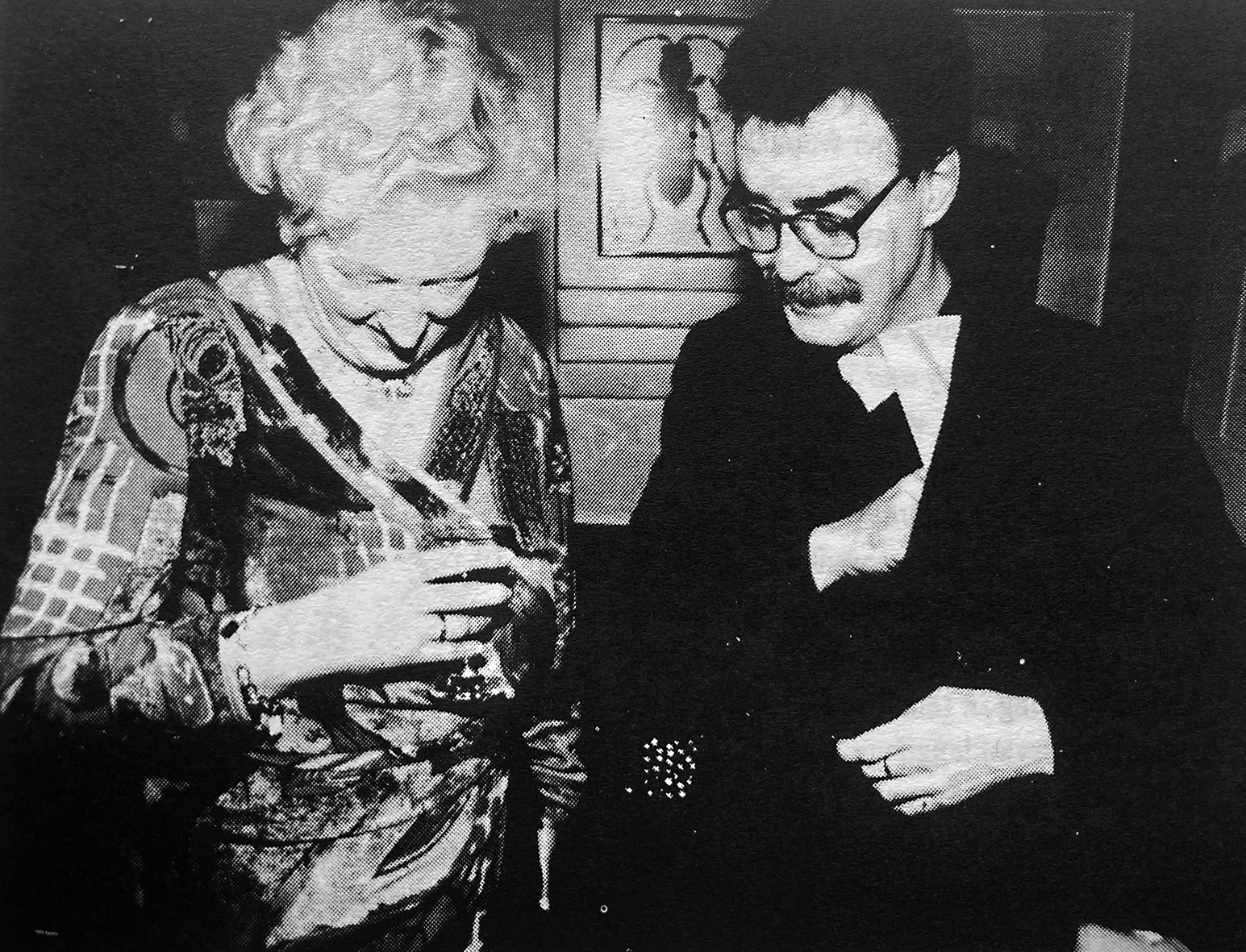

The T. S. Eliot Prize 1993, the first to be awarded, was presented to Ciaran Carson for First Language (Gallery Press) at the Chelsea Arts Club, London, on 20 January 1994. The judging panel comprised Peter Porter (Chair), Edna Longley, John Lucas, and PBS selectors Fleur Adcock and Robert Crawford.

This article was published in the PBS Bulletin spring 1994, number 160, the members’ magazine of the Poetry Book Society. Reproduced by kind permission, www.poetrybooks.co.uk

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘Whether or not poetry is doing well at the moment will go on being debated. In my experience poetry is always on the point of becoming popular: we are always on the threshold of a poetry boom. But it is natural that we should be concerned with our immediate present. After all, this is poetry you don’t need to footnote.’ – Peter Porter, Chair

The Anatomy of a Prize – Peter Porter, Chairman of the judging panel, on the inaugural T. S. Eliot Prize of 1993

There are two very different views of poetry in its own time. In the first, Philip Larkin stresses that the present is always overrated. The second, espoused by the great poet whose name distinguishes this prize, is that we cannot appreciate the past and its achievements if we cease to care for the present. It isn’t that we use the past as insemination of the present (or not only that) but that we will cease to be able to understand the past unless we keep faith with the present.

We are here tonight to honour the second view – T. S. Eliot’s view. Whether or not poetry is doing well at the moment will go on being debated. In my experience poetry is always on the point of becoming popular: we are always on the threshold of a poetry boom. But it is natural that we should be concerned with our immediate present. After all, this is poetry you don’t need to footnote.

The Eliot Prize is not concerned with generations, or geographical or ethnic considerations. It simply aims to pick the best original book of poems in English published in Great Britain during the past year. To that end, we, the judges, read more than 100 volumes. We were made to work hard by the sheer high quality of the work we examined. We neither wanted nor were able to be parti pris. To this end, I’d remind you of statements by two of the poets shortlisted. Firstly, Les Murray, who has remarked of the readership of poetry in English, ‘We’re Country and Western.’ Secondly, James Fenton, who writes, ‘This is no time for people who say: this, this and only this. We say: this and this and that too.’ We ended up with the conviction that poetry is in good health today. If it is held by many to be irrelevant to matters of contemporary living, it remains as central as ever to the mystery of language.

In 1759 Christopher Smart wrote ‘For the English tongue shall be the language of the West.’ Admittedly he was mad at the time and confined to Bedlam. But his prophecy has come to pass. Consider the shortlist of our poets and the composition of our judging panel. They come from the compass points of both hemispheres. The judges hail from England, Scotland, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand. The poets from the same spread of place except that the United States is substituted for New Zealand. English speakers have developed into several nations of poets.

This is not the time or place to go through the many talents and gifts of our ten shortlisted poets. It was hard enough for the judges to come to a decision, without now looking out the markings. The input made by the members’ vote was taken fully into account. The argument was long and exhausting, but will now be instantly resolved. The winner of the first T. S. Eliot Prize for the best original book of poetry published in the UK in 1993 is Ciaran Carson.

The T. S. Eliot Prize 1993, the first to be awarded, was presented to Ciaran Carson for First Language (Gallery Press) at the Chelsea Arts Club, London, on 20 January 1994. The judging panel comprised Peter Porter (Chair), Edna Longley, John Lucas, and PBS selectors Fleur Adcock and Robert Crawford.

This article was published in the PBS Bulletin spring 1994, number 160, the members’ magazine of the Poetry Book Society. Reproduced by kind permission, www.poetrybooks.co.uk