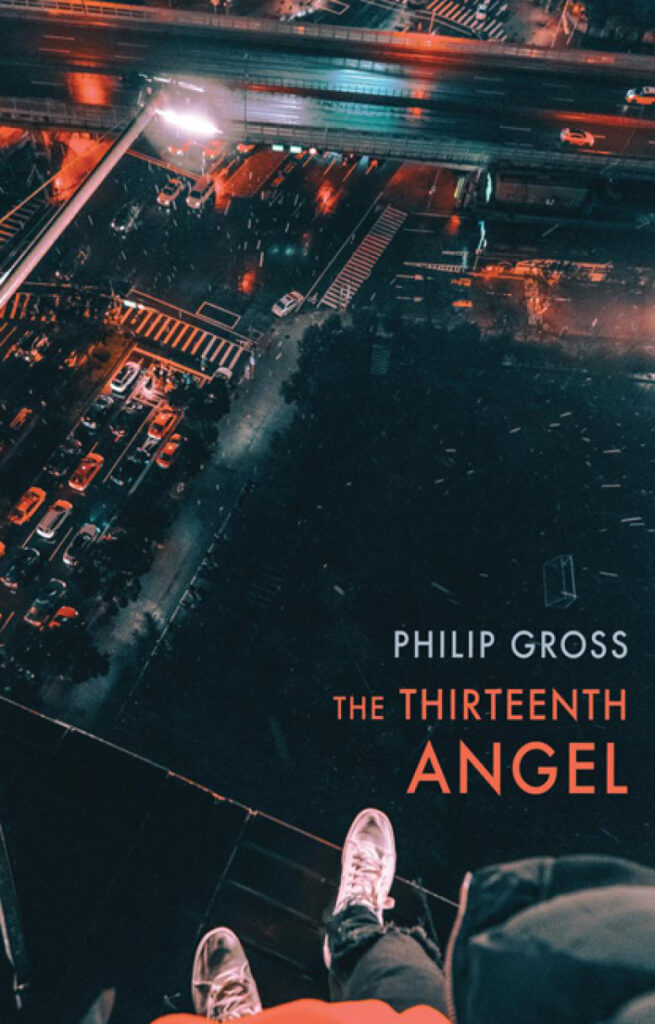

Philip Gross was born in Cornwall, the son of an Estonian wartime refugee. He has lived in Plymouth, Bristol and South Wales, where he was Professor of Creative Writing at Glamorgan University (USW). His twenty-eighth book of poetry, The Shores of Vaikus, was published by Bloodaxe in 2024. His previous collection, The Thirteenth Angel (2022), was a Poetry Book Society...

Review

Interview

Review

Philip Gross, winner of the 2009 T. S. Eliot Prize with The Water Table, has been shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2022 for his twenty-seventh collection, The Thirteenth...

Interview

‘We are all desperately and rightly confused and unsettled about what’s going on around us. Is that a comfort? No, perhaps not, but it is life’, Philip Gross comments in his T. S. Eliot Prize interview film. We asked him about his shortlisted collection The Thirteenth Angel (Bloodaxe, 2022) – and how poetry can help

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

Philip Gross reads from The Thirteenth Angel at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Aliyah Begum reviews Philip Gross‘s The Thirteenth Angel

Philip Gross talks about his work

Philip Gross reads ‘Of Breath (Thirteen Angels)’

Philip Gross reads ‘Moon, O’

Philip Gross reads ‘In the Light of the Times (Springtime in Pandemia, 4)’

Related News Stories

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2022 is Anthony Joseph for his collection Sonnets for Albert published by Bloomsbury Poetry.

The T. S. Eliot Prize and The Poetry Society have now published the first set of video reviews created by participants in the new Young Critics Scheme.

Judges Jean Sprackland (Chair), Hannah Lowe and Roger Robinson have chosen the 2022 T. S. Eliot Prize shortlist from a record 201 poetry collections submitted by British and Irish publishers. The eclectic list comprises seasoned poets, including one previous winner, and five debut collections. Victoria Adukwei Bulley – Quiet (Faber &...

Neil Astley of Bloodaxe Books on a poetry list that has always been avowedly adventurous and internationalist We are delighted to have another pair of Bloodaxe collections on the T. S. Eliot Prize 2021 Shortlist: Hannah Lowe’s third collection The Kids and Selima Hill’s twentieth, Men Who Feed Pigeons. Two...