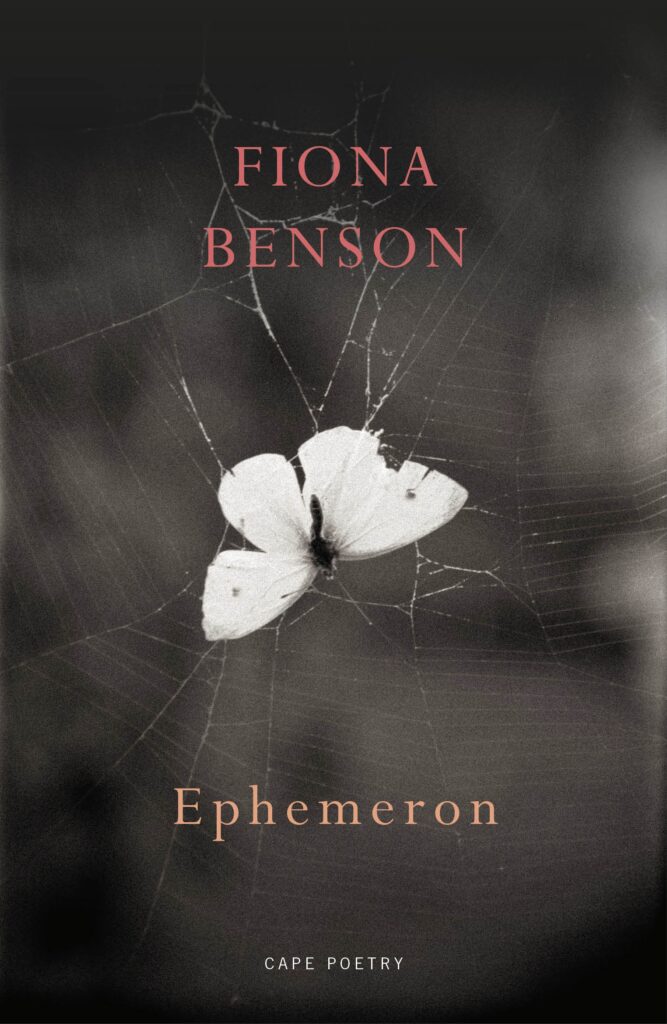

Fiona Benson lives in Devon with her husband and their two daughters. She has published three previous collections of poetry, all of which were shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize: Bright Travellers, which won the 2015 Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize and the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry’s Prize for First Full Collection, Vertigo & Ghost, which was shortlisted for the...

Review

Interview

Review

'If Vertigo & Ghost explored male violence, then Ephemeron sees Fiona Benson turning her gaze towards the monstrous pain of motherly love', writes John Field

Interview

‘Sometimes stories seem to fall in from another world, and writing the poem is just a way of listening to them’, says Fiona Benson, whose Ephemeron (Cape Poetry, 2022) is shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2022. We asked Fiona about stories and other worlds

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

Fiona Benson reads from Ephemeron at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Noah Jacob reviews Fiona Benson‘s Ephemeron

Fiona Benson talks about her work

Fiona Benson reads ‘Ariadne on Asterios’s Imprisonment in the Labyrinth’

Fiona Benson reads ‘Edelweiss’

Fiona Benson reads ‘Mama Cockroach, I Love You…’

Related News Stories

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2022 is Anthony Joseph for his collection Sonnets for Albert published by Bloomsbury Poetry.

The T. S. Eliot Prize and The Poetry Society have now published the first set of video reviews created by participants in the new Young Critics Scheme.

Judges Jean Sprackland (Chair), Hannah Lowe and Roger Robinson have chosen the 2022 T. S. Eliot Prize shortlist from a record 201 poetry collections submitted by British and Irish publishers. The eclectic list comprises seasoned poets, including one previous winner, and five debut collections. Victoria Adukwei Bulley – Quiet (Faber &...