2023

T. S. Eliot Prize

Winner

Jason Allen-Paisant is a Jamaican writer and academic who works as a senior lecturer in Critical Theory and Creative Writing at the University of Manchester. He’s the author of two poetry collections, Thinking with Trees (Carcanet Press, 2021), winner of the 2022 OCM Bocas Prize for poetry, and Self-Portrait as Othello (Carcanet Press, 2023), which won the Forward Prize for Best Collection as well as the T. S. Eliot Prize. His non-fiction book, The Possibility of Tenderness, will be published in 2025. Author photo © Adrian Pope for the T. S. Eliot Prize

The Chair of the judges’ speech

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘Jason Allen-Paisant’s Self-Portrait as Othello scrutinises the legacy of an imperialist past and its complex history within the framework of a poetic memoir’. Chair of judges Paul Muldoon summarised the T. S. Eliot Prize 2023 shortlist at the Award Ceremony on 15 January 2024, from descriptions written by him and fellow judges Sasha Dugdale and Denise Saul.

T. S. Eliot 2023: speech by Paul Muldoon, Chair of judges

Jason Allen-Paisant’s Self-Portrait as Othello scrutinises the legacy of an imperialist past and its complex history within the framework of a poetic memoir. Allen-Paisant manages to wed different registers of European languages – French, Italian and German – with Caribbean patois. Speech is conscious of itself as a poetic performance: ‘I call you daddy bois d’ébène pieces of scattered wood /disappeared and blasted scattered’.

Joe Carrick-Varty’s More Sky confronts fraught spaces of addiction and domestic violence. At the heart of this elegiac debut is the long sequence of poems ‘sky doc’: ‘Once upon a time when suicide was the sky / above a demolished building’. His lyricism is shaped by a raw and fragmented reality of ‘some pocketed galaxy’, dodos and a cosmological map. Repetition and unsettling rhythms define the collection.

The title of Jane Clarke’s A Change in the Air rather neatly conjures the country dweller’s sensitivity to the slightest shift in the weather, literal or figurative, meteorological or emotional. Though she may be influenced by Patrick Kavanagh, by Ted Hughes, and by Alice Oswald, Jane Clarke manages to plow her own furrow in poems of farm and family life that are notable for their attentiveness to, and delight in, the telling detail.

Kit Fan’s The Ink Cloud Reader includes poems set in locations as diverse as a photocopying room and ‘Derek Jarman’s Garden’ where ‘first the waves spoke Shinglese but the shingle / didn’t sing in a single tongue’. Kit Fan is indeed wide-ranging in developing multiple strategies for meeting everything from ‘three days of hard labour’ through earthquakes to other tremors.

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris is a testimony to the poet’s resilience in the face of cancer, intercutting the insurrection at the US Capitol with her impending mastectomy, moving between tough-mindedness and tenderness towards her nearest and dearest: ‘You issue commands / like an old man, then take out / my trash like a young boy / with a crush.’

The disparate strands of Ishion Hutchinson’s School of Instructions are drawn together in the central character of Godspeed, who is a boy growing up in post-colonial rural Jamaica, as well as a West Indian volunteer serving in the First World War in the Middle East. A modernist and fragmented narrative reminiscent of David Jones’ In Parenthesis, School of Instruction explores myth, war, injustice in poetic prose that is both sensual, dramatic and deeply learned.

Feral, sensual, erudite and bright-eyed, the creature that gives its name to Fran Lock’s Hyena! is a compelling guide to Britain’s underbelly: ‘what are the English after all, but / a row of mouths wetly lusting?’ asks ‘hyena in a time of cholera’. A howl of protest and fury, Hyena’s voice is richly musical, with echoes of Blake, the broadsheet and the botanical compendium.

In The Map of the World a fierce and roving poetic imagination illuminates the mysteries of the past. Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin draws history into the present with poems about illness and personal loss alongside tragedies of the twentieth century, and the silent spaces of history. The spiritual and the artistic are held in close association in ‘a space that is yours / for a time, judged and recalled’.

Balladz by Sharon Olds is a collection that celebrates the robustness of one of the oldest stanzaic patterns used in English. There are poems written in the manner of its close relative, the hymn, viewed through the prism of Emily Dickinson. There are poems set in quarantine. There are poems about mouse traps and tear glands. And, of course, there are multiple poems about multiple orgasms.

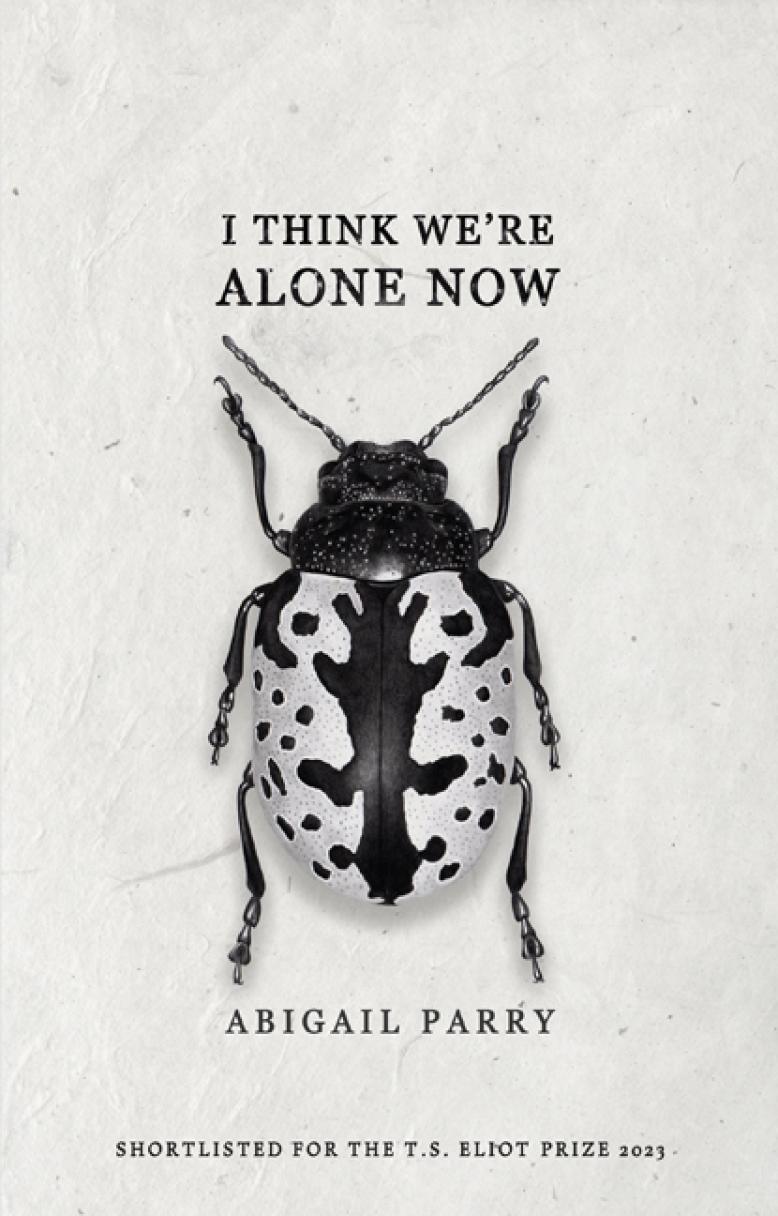

Abigail Parry’s I Think We’re Alone Now holds a transformative power as it is filtered through the idea of solitude. Parry is a lyricist who is attentive to the physicality of imagery, word choice and sound. Poems are saturated with images of sonic texture or a ‘whine in the word’. Ever observant Parry forces us to fixate on playful associations with pop music, film and footnotes.

The winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2023, in its 30th anniversary year, is Jason Allen-Paisant for Self-Portrait as Othello.

Chair of judges Paul Muldoon summarised the T. S. Eliot Prize 2023 shortlist from descriptions written by him and fellow judges Sasha Dugdale and Denise Saul at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2023 Award Ceremony at the Wallace Collection, London, on 15 January 2024.

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘Jason Allen-Paisant’s Self-Portrait as Othello scrutinises the legacy of an imperialist past and its complex history within the framework of a poetic memoir’. Chair of judges Paul Muldoon summarised the T. S. Eliot Prize 2023 shortlist at the Award Ceremony on 15 January 2024, from descriptions written by him and fellow judges Sasha Dugdale and Denise Saul.

T. S. Eliot 2023: speech by Paul Muldoon, Chair of judges

Jason Allen-Paisant’s Self-Portrait as Othello scrutinises the legacy of an imperialist past and its complex history within the framework of a poetic memoir. Allen-Paisant manages to wed different registers of European languages – French, Italian and German – with Caribbean patois. Speech is conscious of itself as a poetic performance: ‘I call you daddy bois d’ébène pieces of scattered wood /disappeared and blasted scattered’.

Joe Carrick-Varty’s More Sky confronts fraught spaces of addiction and domestic violence. At the heart of this elegiac debut is the long sequence of poems ‘sky doc’: ‘Once upon a time when suicide was the sky / above a demolished building’. His lyricism is shaped by a raw and fragmented reality of ‘some pocketed galaxy’, dodos and a cosmological map. Repetition and unsettling rhythms define the collection.

The title of Jane Clarke’s A Change in the Air rather neatly conjures the country dweller’s sensitivity to the slightest shift in the weather, literal or figurative, meteorological or emotional. Though she may be influenced by Patrick Kavanagh, by Ted Hughes, and by Alice Oswald, Jane Clarke manages to plow her own furrow in poems of farm and family life that are notable for their attentiveness to, and delight in, the telling detail.

Kit Fan’s The Ink Cloud Reader includes poems set in locations as diverse as a photocopying room and ‘Derek Jarman’s Garden’ where ‘first the waves spoke Shinglese but the shingle / didn’t sing in a single tongue’. Kit Fan is indeed wide-ranging in developing multiple strategies for meeting everything from ‘three days of hard labour’ through earthquakes to other tremors.

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris is a testimony to the poet’s resilience in the face of cancer, intercutting the insurrection at the US Capitol with her impending mastectomy, moving between tough-mindedness and tenderness towards her nearest and dearest: ‘You issue commands / like an old man, then take out / my trash like a young boy / with a crush.’

The disparate strands of Ishion Hutchinson’s School of Instructions are drawn together in the central character of Godspeed, who is a boy growing up in post-colonial rural Jamaica, as well as a West Indian volunteer serving in the First World War in the Middle East. A modernist and fragmented narrative reminiscent of David Jones’ In Parenthesis, School of Instruction explores myth, war, injustice in poetic prose that is both sensual, dramatic and deeply learned.

Feral, sensual, erudite and bright-eyed, the creature that gives its name to Fran Lock’s Hyena! is a compelling guide to Britain’s underbelly: ‘what are the English after all, but / a row of mouths wetly lusting?’ asks ‘hyena in a time of cholera’. A howl of protest and fury, Hyena’s voice is richly musical, with echoes of Blake, the broadsheet and the botanical compendium.

In The Map of the World a fierce and roving poetic imagination illuminates the mysteries of the past. Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin draws history into the present with poems about illness and personal loss alongside tragedies of the twentieth century, and the silent spaces of history. The spiritual and the artistic are held in close association in ‘a space that is yours / for a time, judged and recalled’.

Balladz by Sharon Olds is a collection that celebrates the robustness of one of the oldest stanzaic patterns used in English. There are poems written in the manner of its close relative, the hymn, viewed through the prism of Emily Dickinson. There are poems set in quarantine. There are poems about mouse traps and tear glands. And, of course, there are multiple poems about multiple orgasms.

Abigail Parry’s I Think We’re Alone Now holds a transformative power as it is filtered through the idea of solitude. Parry is a lyricist who is attentive to the physicality of imagery, word choice and sound. Poems are saturated with images of sonic texture or a ‘whine in the word’. Ever observant Parry forces us to fixate on playful associations with pop music, film and footnotes.

The winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2023, in its 30th anniversary year, is Jason Allen-Paisant for Self-Portrait as Othello.

Chair of judges Paul Muldoon summarised the T. S. Eliot Prize 2023 shortlist from descriptions written by him and fellow judges Sasha Dugdale and Denise Saul at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2023 Award Ceremony at the Wallace Collection, London, on 15 January 2024.