2025

T. S. Eliot Prize

Winner

The Chair of the judges’ speech

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘It seems […] that there’s been a turn to abstract speech, inhuman speech, impersonal speech. Something randomised, a distrust of language, even a dislike of language. Arnold’s criticism of life has devolved to a criticism of language. A poem is now the home for randomised and intelligent and inorganic speech. A conveyor of information. A kind of insider trading. The books we shortlisted here are either exceptional, virtuosic instances of that, or they are irregular, violations, not subject to these loosely described trends. I want to congratulate the authors.’ – Michael Hofmann, Chair

T. S. Eliot Prize 2025: the Chair of judges’ speech, by Michael Hofmann

Good evening, happy Martin Luther King Day

I call to mind the Auden statement, probably mis-reported or mis-remembered, that: ‘Poetry makes nothing happen’, and I think: well, at least there’s that. Do no harm. Hippocrates, not hypocrisy. Given what does happen, doesn’t nothing feel preferable to something? So, there are these shapes on the page, these broken off lines, vulnerable and inefficient, unviable, uneconomical, these inked simulacra of a human voice, and the weeks and months that some people take over making them, and the minutes and hours that – sometimes the same people – spend while reading them. What’s not to like? It feels like a little ray of sunshine, if that comparison isn’t already too toxic. Would that there were more of that, the concomitant silence, the pottery concentration ‘about the time I own’, the doing something invisible and, in real world terms, supposedly inconsequential. This thing that the incomparable Les Murray describes in ‘First Essay on Interest’:

Interest. Mild and inherent with fire as oxygen,

It is a sporadic inhalation. We can live long days

Under its surface, breathing material airThen something catches, is itself. Intent and special silence.

This is interest, that blinks our interests out

And alone permits their survival, by relievingUs of their gravity, for a timeless moment;

That centres where it points, and points to centering,

That centres us where it points, and reflects our centre.

Or that Gottfried Benn, more bitterly and pithily, called ‘the unremunerated work of the spirit’.

Patience and Niall and I read – I totted them up – some ten thousand pages of poetry these past months. Separate experiences were had, so no doubt too different experiences. Here are a few of mine. Books starting on page 1 (something I deprecate). Books longer than I remember books being. What happened to 48 pp? Or even 64 pp? Books coming with pages, sometimes many pages, of notes. More thanks in them than an Oscar speech. Ultimate perfectibility of layout has been attained, a kind of visual bullying, even visual cant, I think. What Randall Jarrell called poems written on typewriters by typewriters. And of course too, as per Jarrell, the stacks of signed plaster casts, with the awful unvarying refrain: it hurts here. At the same time, poets and books all desperately presented as going concerns. I miss the absence of fluff and puff, a kind of austerity, demureness of representation. Dignity.

It seems too that there’s been a turn to abstract speech, inhuman speech, impersonal speech. Something randomised, a distrust of language, even a dislike of language. Arnold’s criticism of life has devolved to a criticism of language. A poem is now the home for randomised and intelligent and inorganic speech. A conveyor of information. A kind of insider trading. The books we shortlisted here are either exceptional, virtuosic instances of that, or they are irregular, violations, not subject to these loosely described trends. I want to congratulate the authors. Alphabetically, in no particular order:

Gillian Allnutt – Lode carries echoes of Geoffrey Hill and Basil Bunting in her tender musings on words and plants and walks and persons over a long life, ‘the now and then of wood pigeon / its dear inconsequential circumlocution’.

Isabelle Baafi – Chaotic Good quantities of imagination and intensity matched by discipline. A wild, even a ferocious poetry with folktale simplicity, bitter puns and little waste. ‘[Y]ours with the flick of a pain’ or ‘He had a wisdom deep enough to stand in, and I did’.

Catherine-Esther Cowie – Heirloom: beautiful audible mingling of Creole and English, ranging up and down her family tree, singing the history of generations of cruelty and colonial violence and a desperate longing for tenderness.

Paul Farley – When It Rained for a Million Years: sprightly, smart, good-humoured poems, attractive and resourceful. Many outstanding individual poems: about a butcher’s block, about the poet’s room way back when, about beavers, about turkeys and cows. To anyone who’s read the book, you have only to name the subject, and a smile will pass across their face. Nothing arcane, deeply familiar things, ‘A roof joist cracking. The pilot light bumping on’ just marmalised.

Vona Groarke – Infinity Pool is a book very low on names and labels, the expected authenticity markers, but very close to a real sense of the speaker who may or may not be the poet. Numbers of very short poems are also a rarity these days. Overall, there’s a sense of a ravel of feelings, not noisy but all the more genuine. Poems spun, it seems, out of sheer air.

Sarah Howe – Foretokens: a neat and very deliberate language-y poetry on successive generations that manages to be both personal and impersonal; palimpsests, erasures, recordings, ekphrases, concrete poems, the DNA of her preoccupations twisting and doubling back on itself.

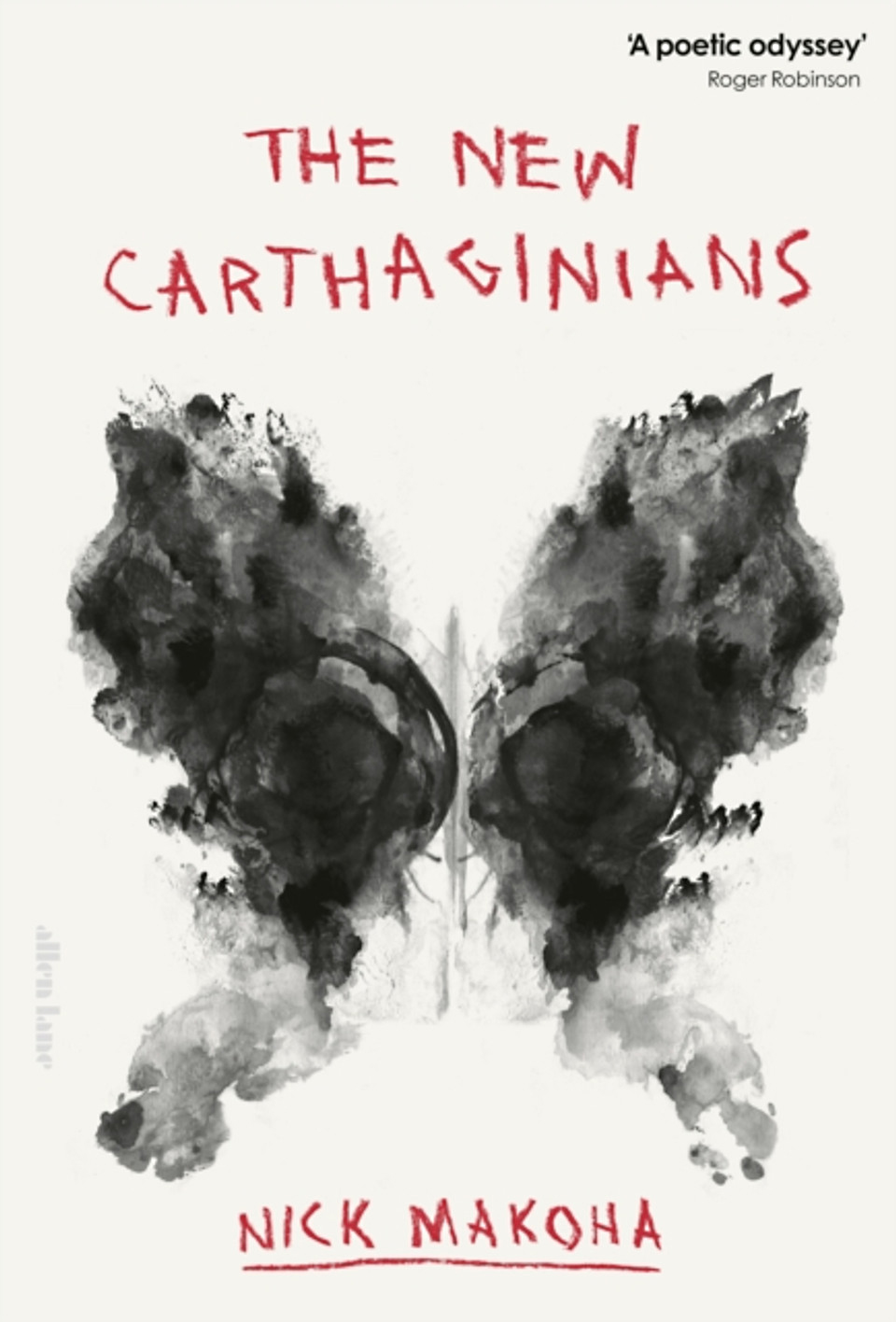

Nick Makoha – The New Carthaginians reads like a synthesised global thriller, Basquiat and Icarus and Carlos the Jackal and the poet’s father whirled past the eye of the reader in blocks of type comprising short, dramatic sentences. A Hollywood armature with its own playlist, set in a bold and gumptious shuffle.

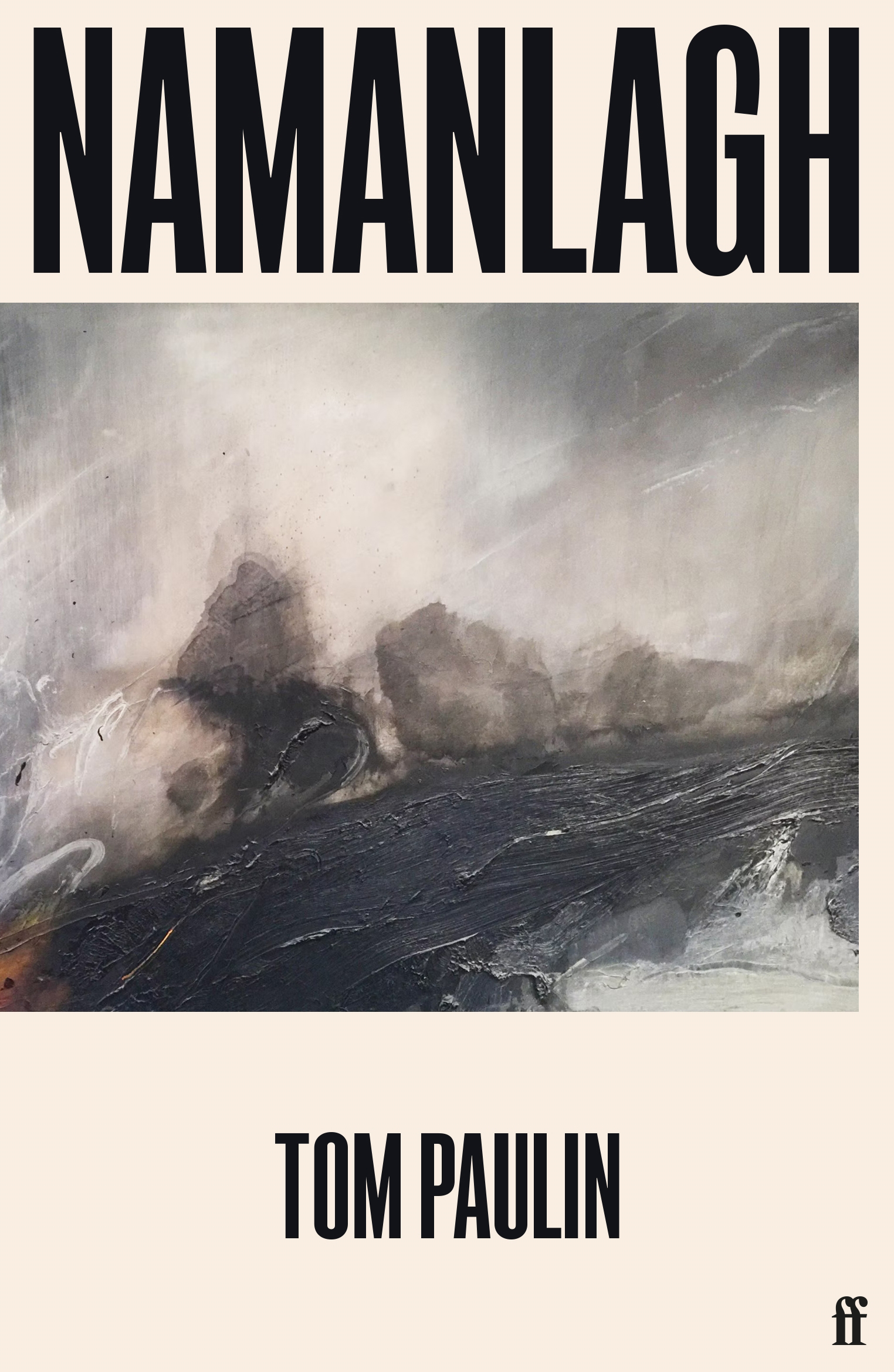

Tom Paulin – Namanlagh: these might be described as Tom Paulin’s retrobottega poems, poems that came into being unknown to anyone, practically to the poet himself as two friends, Jamie McKendrick and Bernard O’Donoghue, took receipt of the poems from Paulin’s wife Giti, and made them into a manuscript describing struggles with depression, memories of the Troubles and even further back in Ulster history. He has given us the double negative in a new way: ‘[N]either this time nor this place / is right for you’. Or ‘[S]ome rugged province / you’d quite like to visit / but not now and not yet’. Paulin’s trademark style, very short abrupt lines with full rhymes and a sour or bitter speaker is on magnificent display here.

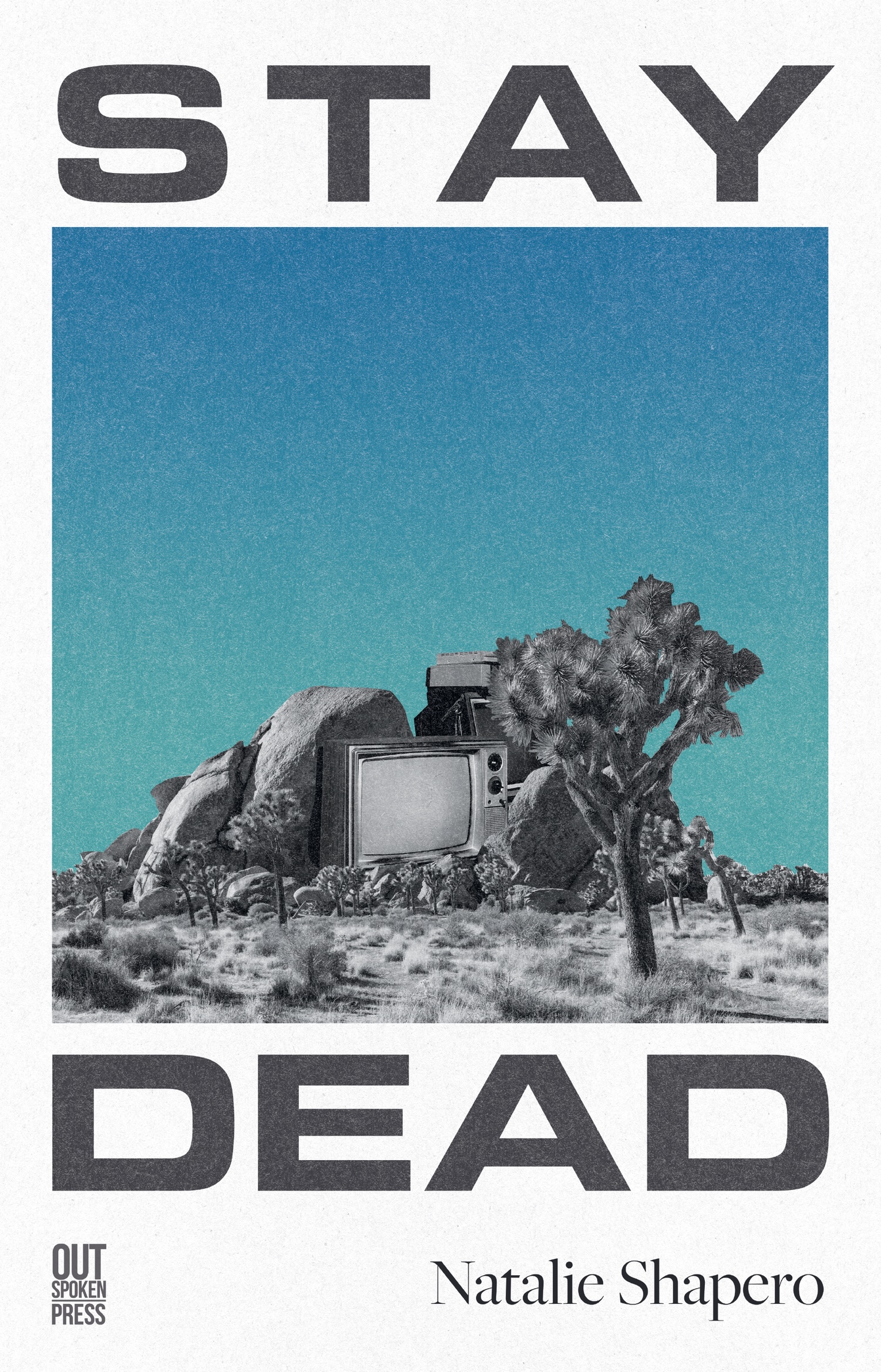

Natalie Shapero – Stay Dead: who says Americans can’t do irony? But probably the entire nation’s annual supply is all with Shapero, who writes dry, nimble, defeatist, and cleverly recursive poems. Based now in LA, she works through the film industry, while also taking in signal non-actors like Monet and Rothko. It’s not blood, it’s red, she cites that other ironist, Jean-Luc Godard.

Karen Solie – Wellwater: the death of Karen Solie’s father, a farmer in the Canadian mid-West seems to have brought the poet back there for longer, to consider the place where she grew up, and the changes that have befallen it. Solie brings her characteristic sympathy for other living creatures, a swooping of intellectual content and surprise, and a new emphasis on ethics.

The winner is Karen Solie!

This speech was given by Michael Hofmann, Chair of judges, at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2025 Award Ceremony at the Wallace Collection, London, on 19 January 2026.

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘It seems […] that there’s been a turn to abstract speech, inhuman speech, impersonal speech. Something randomised, a distrust of language, even a dislike of language. Arnold’s criticism of life has devolved to a criticism of language. A poem is now the home for randomised and intelligent and inorganic speech. A conveyor of information. A kind of insider trading. The books we shortlisted here are either exceptional, virtuosic instances of that, or they are irregular, violations, not subject to these loosely described trends. I want to congratulate the authors.’ – Michael Hofmann, Chair

T. S. Eliot Prize 2025: the Chair of judges’ speech, by Michael Hofmann

Good evening, happy Martin Luther King Day

I call to mind the Auden statement, probably mis-reported or mis-remembered, that: ‘Poetry makes nothing happen’, and I think: well, at least there’s that. Do no harm. Hippocrates, not hypocrisy. Given what does happen, doesn’t nothing feel preferable to something? So, there are these shapes on the page, these broken off lines, vulnerable and inefficient, unviable, uneconomical, these inked simulacra of a human voice, and the weeks and months that some people take over making them, and the minutes and hours that – sometimes the same people – spend while reading them. What’s not to like? It feels like a little ray of sunshine, if that comparison isn’t already too toxic. Would that there were more of that, the concomitant silence, the pottery concentration ‘about the time I own’, the doing something invisible and, in real world terms, supposedly inconsequential. This thing that the incomparable Les Murray describes in ‘First Essay on Interest’:

Interest. Mild and inherent with fire as oxygen,

It is a sporadic inhalation. We can live long days

Under its surface, breathing material airThen something catches, is itself. Intent and special silence.

This is interest, that blinks our interests out

And alone permits their survival, by relievingUs of their gravity, for a timeless moment;

That centres where it points, and points to centering,

That centres us where it points, and reflects our centre.

Or that Gottfried Benn, more bitterly and pithily, called ‘the unremunerated work of the spirit’.

Patience and Niall and I read – I totted them up – some ten thousand pages of poetry these past months. Separate experiences were had, so no doubt too different experiences. Here are a few of mine. Books starting on page 1 (something I deprecate). Books longer than I remember books being. What happened to 48 pp? Or even 64 pp? Books coming with pages, sometimes many pages, of notes. More thanks in them than an Oscar speech. Ultimate perfectibility of layout has been attained, a kind of visual bullying, even visual cant, I think. What Randall Jarrell called poems written on typewriters by typewriters. And of course too, as per Jarrell, the stacks of signed plaster casts, with the awful unvarying refrain: it hurts here. At the same time, poets and books all desperately presented as going concerns. I miss the absence of fluff and puff, a kind of austerity, demureness of representation. Dignity.

It seems too that there’s been a turn to abstract speech, inhuman speech, impersonal speech. Something randomised, a distrust of language, even a dislike of language. Arnold’s criticism of life has devolved to a criticism of language. A poem is now the home for randomised and intelligent and inorganic speech. A conveyor of information. A kind of insider trading. The books we shortlisted here are either exceptional, virtuosic instances of that, or they are irregular, violations, not subject to these loosely described trends. I want to congratulate the authors. Alphabetically, in no particular order:

Gillian Allnutt – Lode carries echoes of Geoffrey Hill and Basil Bunting in her tender musings on words and plants and walks and persons over a long life, ‘the now and then of wood pigeon / its dear inconsequential circumlocution’.

Isabelle Baafi – Chaotic Good quantities of imagination and intensity matched by discipline. A wild, even a ferocious poetry with folktale simplicity, bitter puns and little waste. ‘[Y]ours with the flick of a pain’ or ‘He had a wisdom deep enough to stand in, and I did’.

Catherine-Esther Cowie – Heirloom: beautiful audible mingling of Creole and English, ranging up and down her family tree, singing the history of generations of cruelty and colonial violence and a desperate longing for tenderness.

Paul Farley – When It Rained for a Million Years: sprightly, smart, good-humoured poems, attractive and resourceful. Many outstanding individual poems: about a butcher’s block, about the poet’s room way back when, about beavers, about turkeys and cows. To anyone who’s read the book, you have only to name the subject, and a smile will pass across their face. Nothing arcane, deeply familiar things, ‘A roof joist cracking. The pilot light bumping on’ just marmalised.

Vona Groarke – Infinity Pool is a book very low on names and labels, the expected authenticity markers, but very close to a real sense of the speaker who may or may not be the poet. Numbers of very short poems are also a rarity these days. Overall, there’s a sense of a ravel of feelings, not noisy but all the more genuine. Poems spun, it seems, out of sheer air.

Sarah Howe – Foretokens: a neat and very deliberate language-y poetry on successive generations that manages to be both personal and impersonal; palimpsests, erasures, recordings, ekphrases, concrete poems, the DNA of her preoccupations twisting and doubling back on itself.

Nick Makoha – The New Carthaginians reads like a synthesised global thriller, Basquiat and Icarus and Carlos the Jackal and the poet’s father whirled past the eye of the reader in blocks of type comprising short, dramatic sentences. A Hollywood armature with its own playlist, set in a bold and gumptious shuffle.

Tom Paulin – Namanlagh: these might be described as Tom Paulin’s retrobottega poems, poems that came into being unknown to anyone, practically to the poet himself as two friends, Jamie McKendrick and Bernard O’Donoghue, took receipt of the poems from Paulin’s wife Giti, and made them into a manuscript describing struggles with depression, memories of the Troubles and even further back in Ulster history. He has given us the double negative in a new way: ‘[N]either this time nor this place / is right for you’. Or ‘[S]ome rugged province / you’d quite like to visit / but not now and not yet’. Paulin’s trademark style, very short abrupt lines with full rhymes and a sour or bitter speaker is on magnificent display here.

Natalie Shapero – Stay Dead: who says Americans can’t do irony? But probably the entire nation’s annual supply is all with Shapero, who writes dry, nimble, defeatist, and cleverly recursive poems. Based now in LA, she works through the film industry, while also taking in signal non-actors like Monet and Rothko. It’s not blood, it’s red, she cites that other ironist, Jean-Luc Godard.

Karen Solie – Wellwater: the death of Karen Solie’s father, a farmer in the Canadian mid-West seems to have brought the poet back there for longer, to consider the place where she grew up, and the changes that have befallen it. Solie brings her characteristic sympathy for other living creatures, a swooping of intellectual content and surprise, and a new emphasis on ethics.

The winner is Karen Solie!

This speech was given by Michael Hofmann, Chair of judges, at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2025 Award Ceremony at the Wallace Collection, London, on 19 January 2026.