2020

T. S. Eliot Prize

Winner

The Chair of the judges’ speech

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘At times poetry fills stadiums, at others it languishes in desk drawers and on library shelves (although most libraries can no longer afford to buy it, placing it even further out of reach). It never disappears. People turn to poetry when language fails them even if they’ve never read or written a poem before. Is language not now failing us on a daily basis? The rich variety of the 153 books that we read for this prize shows how poetry has caught up with the profound changes and awakenings we have gone through in the first twenty years of this unsettling century. Poetry does not explain or resolve these things but it gives us a way to inhabit the questions that arise.’ – Lavinia Greenlaw, Chair

T. S. Eliot Prize 2020: the Chair of judges’ speech by Lavinia Greenlaw

At times poetry fills stadiums, at others it languishes in desk drawers and on library shelves (although most libraries can no longer afford to buy it, placing it even further out of reach). It never disappears. People turn to poetry when language fails them even if they’ve never read or written a poem before. Is language not now failing us on a daily basis?

The rich variety of the 153 books that we read for this prize shows how poetry has caught up with the profound changes and awakenings we have gone through in the first twenty years of this unsettling century. Poetry does not explain or resolve these things but it gives us a way to inhabit the questions that arise. The best of today’s poets are asserting stylistic freedom and new ways of deploying language that enable them to articulate the truth, however unresolved, as well as to interrogate the constructs on which that truth is based. They share a determination and sense of responsibility drawn from the ways in which the self has been impacted upon and displaced.

My fellow judges Mona Arshi, Andrew McMillan and I were looking for the best poetry we could find. I would like to thank them for their hard work, insight and integrity, as well as the pleasure of those poetry conversations. We were reading work that had been written in a different, pre-pandemic, world and the books that spoke to us were those that could reach across this new divide with the vitality and relevance that all good poetry should contain.

These ten very different books exemplify the ways in which poetry can cast light on what we are only just beginning to see. You will still find the moon, the sea, the sun and stars, in these books, but their metaphorical qualities have been recast. This poetry challenges its readers but it also leaves us newly equipped as we reconfigure our relationship with our world.

Natalie Diaz’s Postcolonial Love Poem explores the intersections of nationhood, selfhood, love (erotic, familial and spiritual) and the very language of survival. Diaz rewrites what cannot be unwritten with technical control matched by her ethical determination and imaginative reach. Heightened rhythms of thought and metaphorical high-wire acts articulate the forces of limit and boundary.

Sasha Dugdale’s Deformations is framed by two powerful sequences drawn from narratives in which art and trauma are inextricable: that of the artist Eric Gill and his abuse of his daughters, and ‘simultaneous fragments’ from the Odyssey which amplify moments of impact, of being acted upon. Most remarkable is the point of the view: a penetrative eye that counters the unwelcome penetrative action of transgression and subjugation.

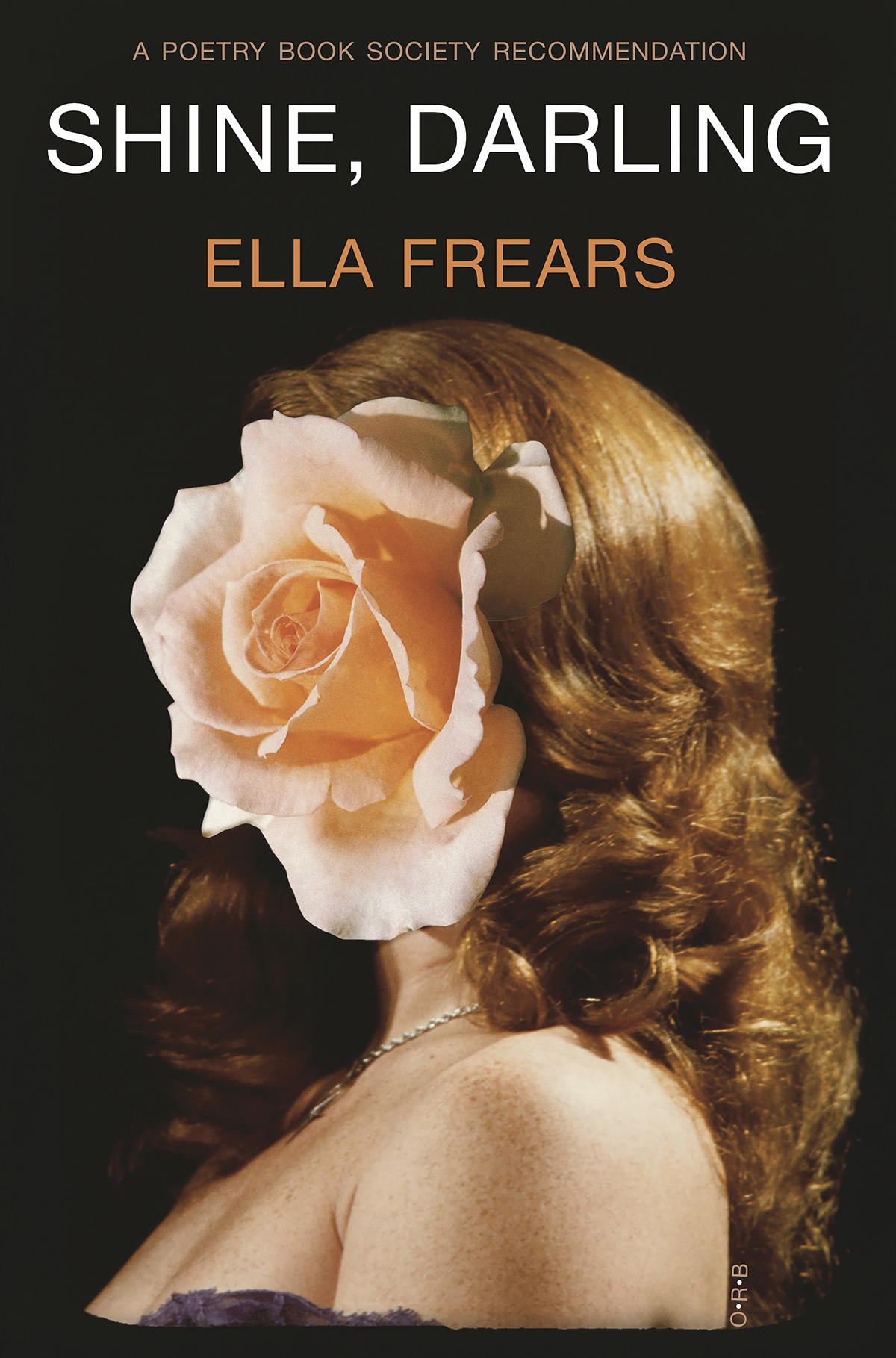

In Shine Darling, Ella Frears uses spontaneity as a form of pursuit so that each new thought brings us closer to the core of the experience she describes. Assertive and courageous, this work of self-interrogation looks at responsibility, volition and desire, and includes a challenging sequence that amplifies the horrifying ordinariness of sexual threat.

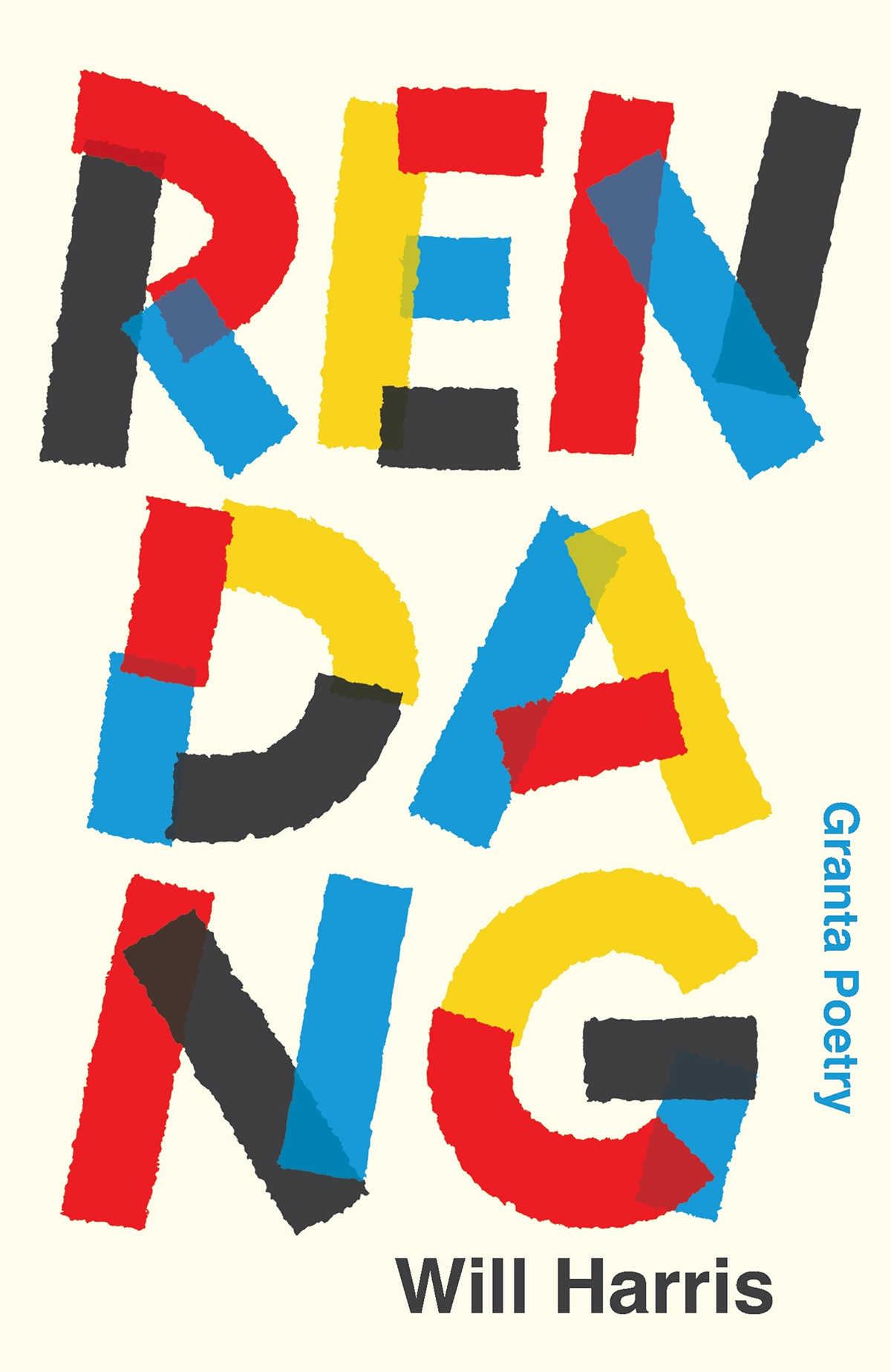

RENDANG by Will Harris explores self-construction and self-awareness, and what is imposed on us by others as well as by ourselves. The book shifts between London and Indonesia as Harris steps deftly between the lyrical and the anecdotal, the essayistic and the philosophical in a compelling investigation that is as literary as it is disruptive.

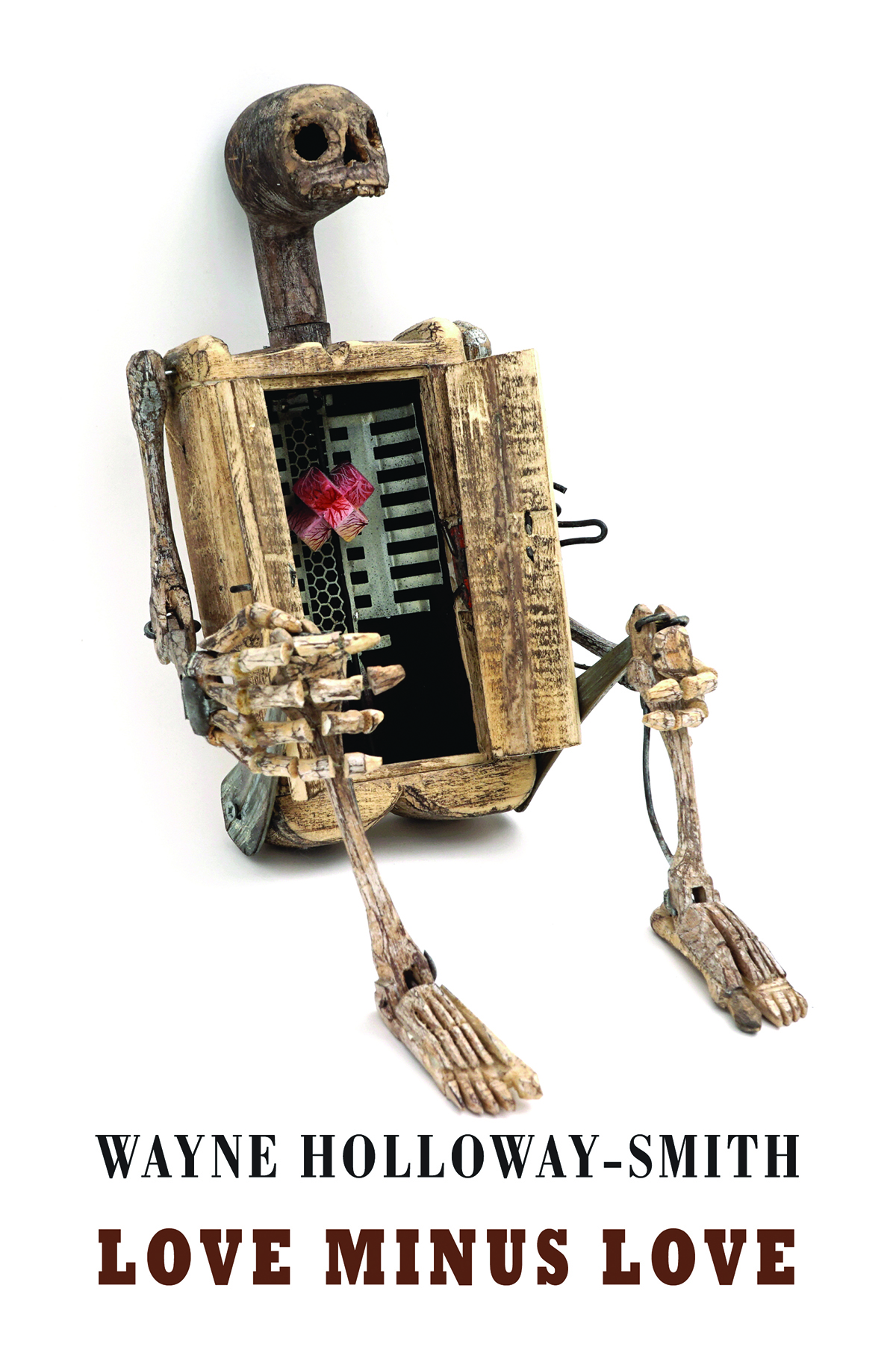

Wayne Holloway-Smith’s Love Minus Love is fiercely playful in its confrontation of truths that are as familiar, and familial, as they are painful: how we are always situated in relation, and how we depend on those dynamics, however toxic, to define ourselves. The work traces the erosion of connection between child and parent, meaning and language, body and self.

Bhanu Kapil’s How to Wash a Heart brings to mind what Edward Said refers to as the ‘discontinuous state of being’ of the immigrant. It is related by an immigrant guest, who is staying in the home of a citizen host. Her disempowerment can only be countered by freedom of thought, which in turn is compromised by the ongoing cost of survival. In this piercing work, the heart, like its owner, is excised, emblematised and recast.

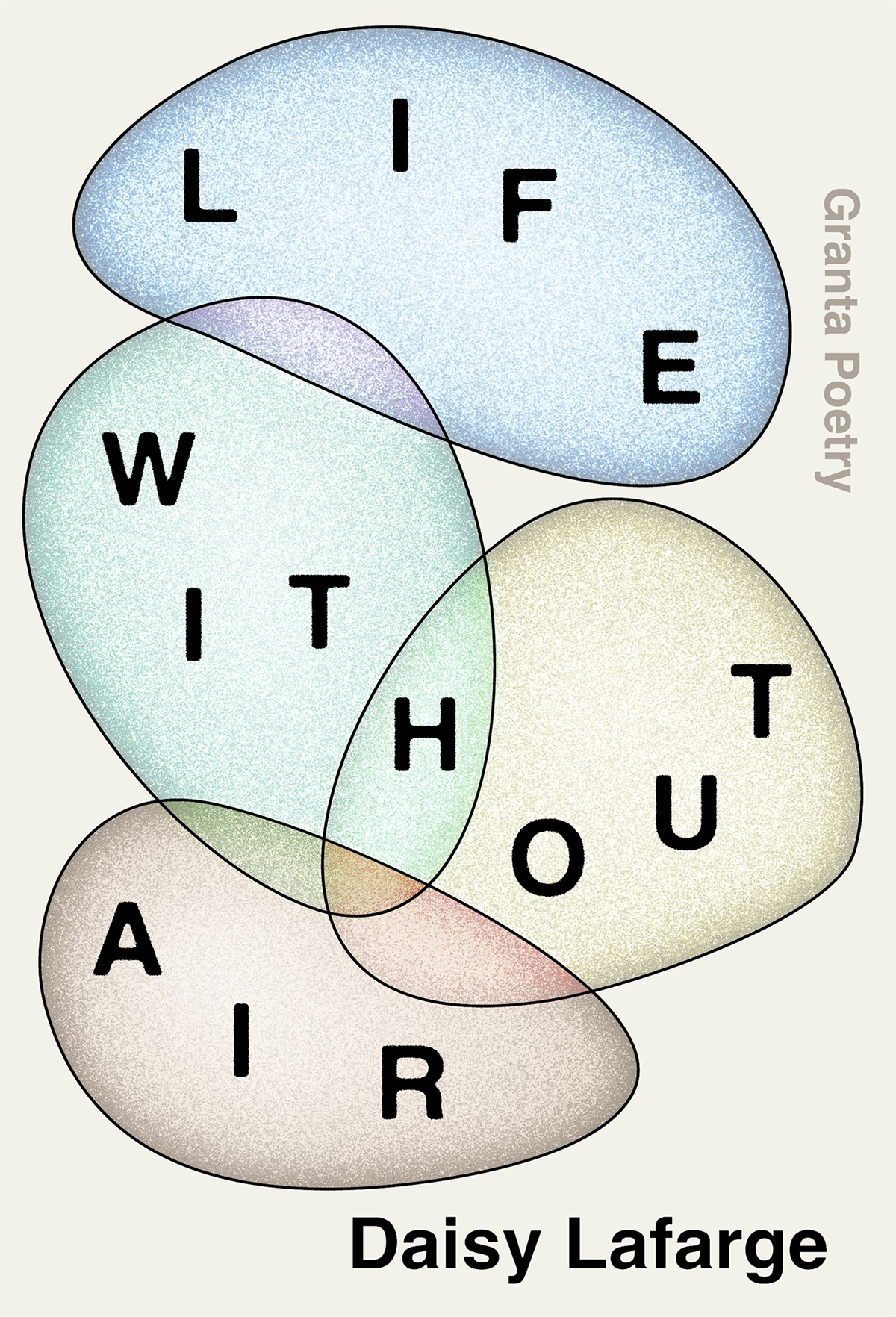

In Daisy Lafarge’s Life Without Air, imperatives are pursued beyond their resources, to the point of life without air, including the simultaneous statement and retraction of what needs to be, but will never be, said. Language reveals its innate conflicts. All this is driven by powerful internal music that integrates seemingly discordant images and ideas into invigorating truths.

Glyn Maxwell’s How the hell are you conjures the future that has already arrived, where truth is a commodity and humans are side-lined above all by their own failure to care, to pay attention, to act. Renewing ancient forms of fable and song, the poet reminds us that the threat we represent to ourselves is also historical and perpetual. This poetry is an urgent call for clear sight and collective responsibility.

Shane McCrae’s Sometimes I Never Suffered considers the structures we use to gather meaning in the form of heaven, limbo and hell. It includes a man wandering through the afterlife and arguing back, as well as a fallen angel, who has been ‘hastily assembled’ and is as unsure of his mission as are those who created him. Its finely crafted but perforated lines reflect how we stitch together our never to be completed identities and beliefs.

In The Martian’s Regress, J. O. Morgan continues his exploration of the long poem to give us a lone Martian on a tragi-comic mission back to earth. Darkly comic and always unsettling, these poems reflect on ‘the natural course of things’ just as they hold a mirror up to our contemporary ecological emergency. Remarkable in its world-building, this work reflects on what we cannot escape, whatever our capacity for reinvention.

The winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2020 is Bhanu Kapil for How to Wash a Heart.

This speech was given during the T. S. Eliot Prize 2020 Shortlist Readings streamed from the Southbank Centre, London, on Sunday 24 January 2021.

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘At times poetry fills stadiums, at others it languishes in desk drawers and on library shelves (although most libraries can no longer afford to buy it, placing it even further out of reach). It never disappears. People turn to poetry when language fails them even if they’ve never read or written a poem before. Is language not now failing us on a daily basis? The rich variety of the 153 books that we read for this prize shows how poetry has caught up with the profound changes and awakenings we have gone through in the first twenty years of this unsettling century. Poetry does not explain or resolve these things but it gives us a way to inhabit the questions that arise.’ – Lavinia Greenlaw, Chair

T. S. Eliot Prize 2020: the Chair of judges’ speech by Lavinia Greenlaw

At times poetry fills stadiums, at others it languishes in desk drawers and on library shelves (although most libraries can no longer afford to buy it, placing it even further out of reach). It never disappears. People turn to poetry when language fails them even if they’ve never read or written a poem before. Is language not now failing us on a daily basis?

The rich variety of the 153 books that we read for this prize shows how poetry has caught up with the profound changes and awakenings we have gone through in the first twenty years of this unsettling century. Poetry does not explain or resolve these things but it gives us a way to inhabit the questions that arise. The best of today’s poets are asserting stylistic freedom and new ways of deploying language that enable them to articulate the truth, however unresolved, as well as to interrogate the constructs on which that truth is based. They share a determination and sense of responsibility drawn from the ways in which the self has been impacted upon and displaced.

My fellow judges Mona Arshi, Andrew McMillan and I were looking for the best poetry we could find. I would like to thank them for their hard work, insight and integrity, as well as the pleasure of those poetry conversations. We were reading work that had been written in a different, pre-pandemic, world and the books that spoke to us were those that could reach across this new divide with the vitality and relevance that all good poetry should contain.

These ten very different books exemplify the ways in which poetry can cast light on what we are only just beginning to see. You will still find the moon, the sea, the sun and stars, in these books, but their metaphorical qualities have been recast. This poetry challenges its readers but it also leaves us newly equipped as we reconfigure our relationship with our world.

Natalie Diaz’s Postcolonial Love Poem explores the intersections of nationhood, selfhood, love (erotic, familial and spiritual) and the very language of survival. Diaz rewrites what cannot be unwritten with technical control matched by her ethical determination and imaginative reach. Heightened rhythms of thought and metaphorical high-wire acts articulate the forces of limit and boundary.

Sasha Dugdale’s Deformations is framed by two powerful sequences drawn from narratives in which art and trauma are inextricable: that of the artist Eric Gill and his abuse of his daughters, and ‘simultaneous fragments’ from the Odyssey which amplify moments of impact, of being acted upon. Most remarkable is the point of the view: a penetrative eye that counters the unwelcome penetrative action of transgression and subjugation.

In Shine Darling, Ella Frears uses spontaneity as a form of pursuit so that each new thought brings us closer to the core of the experience she describes. Assertive and courageous, this work of self-interrogation looks at responsibility, volition and desire, and includes a challenging sequence that amplifies the horrifying ordinariness of sexual threat.

RENDANG by Will Harris explores self-construction and self-awareness, and what is imposed on us by others as well as by ourselves. The book shifts between London and Indonesia as Harris steps deftly between the lyrical and the anecdotal, the essayistic and the philosophical in a compelling investigation that is as literary as it is disruptive.

Wayne Holloway-Smith’s Love Minus Love is fiercely playful in its confrontation of truths that are as familiar, and familial, as they are painful: how we are always situated in relation, and how we depend on those dynamics, however toxic, to define ourselves. The work traces the erosion of connection between child and parent, meaning and language, body and self.

Bhanu Kapil’s How to Wash a Heart brings to mind what Edward Said refers to as the ‘discontinuous state of being’ of the immigrant. It is related by an immigrant guest, who is staying in the home of a citizen host. Her disempowerment can only be countered by freedom of thought, which in turn is compromised by the ongoing cost of survival. In this piercing work, the heart, like its owner, is excised, emblematised and recast.

In Daisy Lafarge’s Life Without Air, imperatives are pursued beyond their resources, to the point of life without air, including the simultaneous statement and retraction of what needs to be, but will never be, said. Language reveals its innate conflicts. All this is driven by powerful internal music that integrates seemingly discordant images and ideas into invigorating truths.

Glyn Maxwell’s How the hell are you conjures the future that has already arrived, where truth is a commodity and humans are side-lined above all by their own failure to care, to pay attention, to act. Renewing ancient forms of fable and song, the poet reminds us that the threat we represent to ourselves is also historical and perpetual. This poetry is an urgent call for clear sight and collective responsibility.

Shane McCrae’s Sometimes I Never Suffered considers the structures we use to gather meaning in the form of heaven, limbo and hell. It includes a man wandering through the afterlife and arguing back, as well as a fallen angel, who has been ‘hastily assembled’ and is as unsure of his mission as are those who created him. Its finely crafted but perforated lines reflect how we stitch together our never to be completed identities and beliefs.

In The Martian’s Regress, J. O. Morgan continues his exploration of the long poem to give us a lone Martian on a tragi-comic mission back to earth. Darkly comic and always unsettling, these poems reflect on ‘the natural course of things’ just as they hold a mirror up to our contemporary ecological emergency. Remarkable in its world-building, this work reflects on what we cannot escape, whatever our capacity for reinvention.

The winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2020 is Bhanu Kapil for How to Wash a Heart.

This speech was given during the T. S. Eliot Prize 2020 Shortlist Readings streamed from the Southbank Centre, London, on Sunday 24 January 2021.