2013

T. S. Eliot Prize

Winner

The Chair of the judges’ speech

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘Sinéad Morrissey’s Parallax is also full of life observed in beautifully-turned language, many-angled and any-angled as her title suggests from, in her ‘Photographs of Belfast by Alexander Robert Hogg’ where she notes ‘each child strong enough / to manage it / carries a child’ through her own heritage as being the child of parents who were members of the Communist Party of Northern Ireland, to meditations on doctored photographs or ‘The Party Bazaar’, detritus from a time when the whole world seemed to be in one or the other of two armed camps.’ – Ian Duhig, Chair

I’d like to start by thanking all the poets we considered, on and off the shortlist, whose excellence demands that we honour them with events such as this, and I’d like to thank Chris Holifield and the Poetry Book Society for organising it and in particular my fellow judges, Imtiaz Dharker and Vicki Feaver, for making my very difficult task a pleasure with their intelligence, patience and insight.

Contemporary poetry is often criticised for being academic in all senses of that word: written for academics by academics and of no consequence to anyone but academics. British contemporary poetry in particular is criticised for its insularity, slow to reflect influences from elsewhere, even in the Anglosphere, for poetry in the English language has long been a global medium.

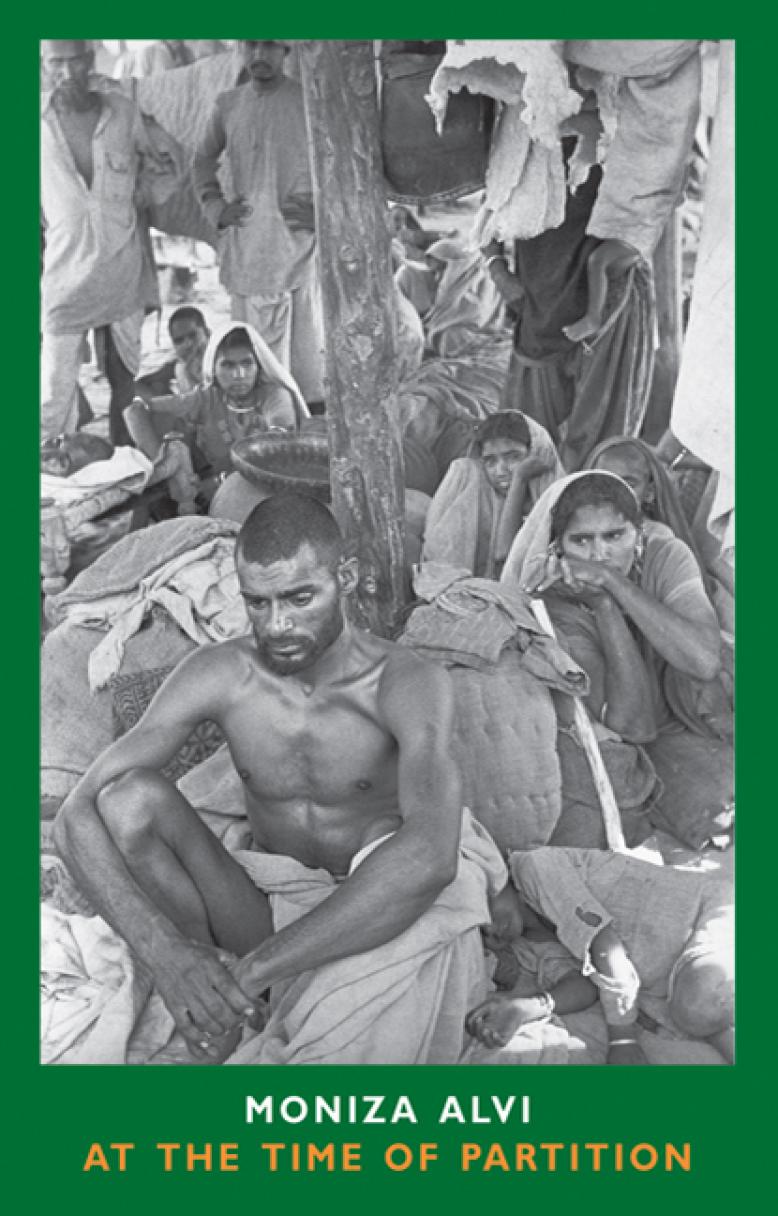

I believe the shortlist for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2013 is neither academic nor insular. Moniza Alvi‘s fine collection At the Time of Partition takes her poetic line for a walk like Klee’s but to pace out the birth of two nations, India and Pakistan, in a moving and powerful book that qualified it for inclusion on this shortlist even before this panel had to consider it by virtue of being a PBS Choice. This is a book that has already had an impact here and abroad, a very considerable work.

The partition of Ireland haunted the work of the late, great Seamus Heaney, a former winner of this Prize, whose voice in turn haunts the poetry of Maurice Riordan. His lush and wonderful collection The Water Stealer demonstrates his own mastery, though, for Maurice is one of the very best poets in these islands and this book shows him writing at the height of his powers. Both in his own poetry and in his work as an editor, now of The Poetry Review, Maurice’s approach is characterised by an internationalism in taste and imagination that all poets here are grateful for.

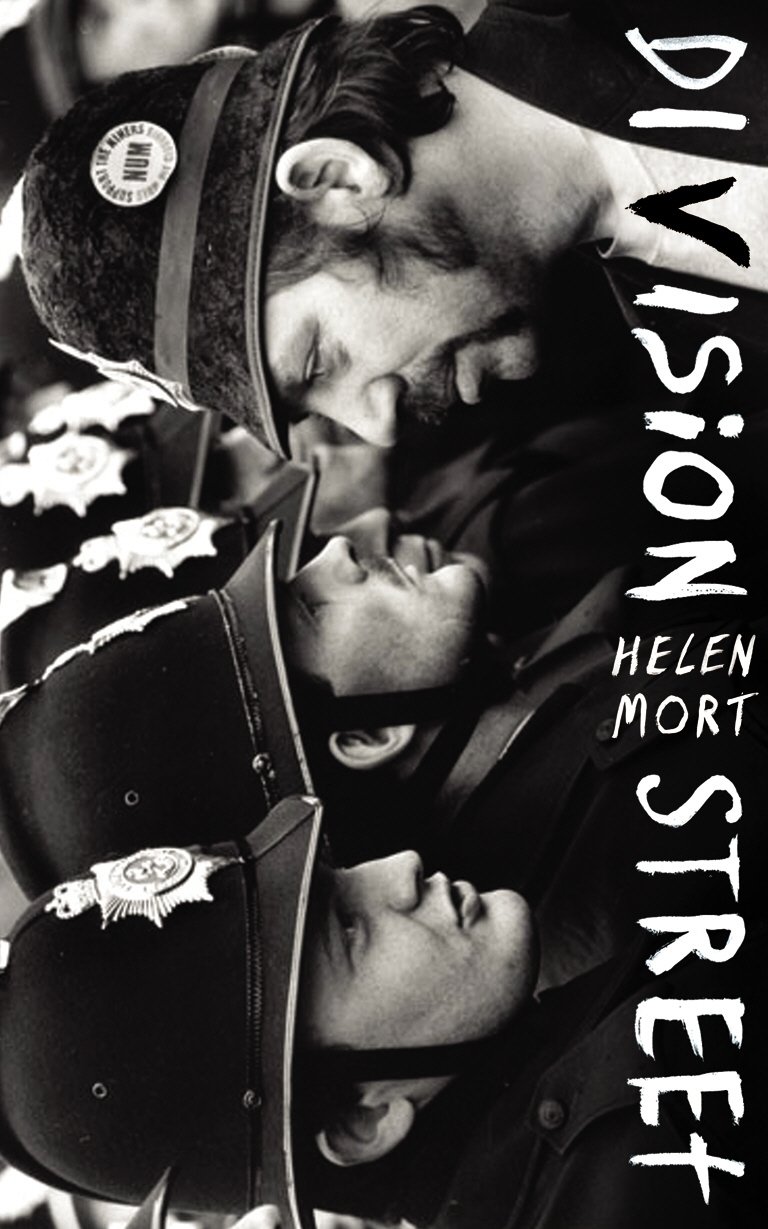

Helen Mort’s Division Street is one of the most celebrated English debuts of the new century, original and carefully-crafted, reflecting, among many other themes, the legacy of social division in this country, particularly to do with the Miners’ Strike of 1984-5, about which there continue to be revelations and scandals. The miner on the cover of her book in that famous photograph of an eyeballing confrontation is now dead, but Helen is vibrantly concerned with living and Division Street is full of life.

Sinéad Morrissey’s Parallax is also full of life observed in beautifully-turned language, many-angled and any-angled as her title suggests from, in her ‘Photographs of Belfast by Alexander Robert Hogg’ where she notes ‘each child strong enough / to manage it / carries a child’ through her own heritage as being the child of parents who were members of the Communist Party of Northern Ireland, to meditations on doctored photographs or ‘The Party Bazaar’, detritus from a time when the whole world seemed to be in one or the other of two armed camps.

PBS Choice and former winner of this Prize, George Szirtes is a child of those political binaries; born and brought up in a Hungary his family fled after the 1956 Uprising. His work as a translator has enriched all our poetry but as a poet himself, he is entirely original. In his book here, Bad Machine, we enjoy the fruits of his deep knowledge of art, George having trained as an artist, in many collaborations with other artists, giving us an inventive range of work taking in the Tottenham riots or Eddy Morganesque word music, as in his ‘Say So’.

Also a previous winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize and a PBS Choice, Anne Carson’s Red Doc>, continuing the story of her earlier Autobiography of Red in what is unquestionably one of the most fascinating books I have ever read of any description. A mixture of prose, poetry and the unclassifiable, when asked recently in an interview how she’d describe Red Doc> Anne answered: “I have no generic name for this farrago.” This seriously undersells a work of breathtaking originality.

PBS Choice Drysalter by Michael Symmons Roberts is already a double major prizewinner, having taken the Forward earlier in the season and the Costa Poetry Award only a week ago. In a book of wonderful beauty and subtlety, the first line from his poem ‘Through a Glass Darkly’, ‘Mist can be a form of mercy’ reminded me of Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows, which was described as ‘a hymn to nuance’. Hymns to nuance run through Drysalter, both profoundly spiritual and deeply rooted in this world and its capacity to sustain love.

Love is, perhaps, the most distinguishing feature of Dannie Abse‘s work both in terms of its subject matter and how it is received. I honestly cannot think of any writer who is held in greater affection than Dannie, and his new book on our shortlist, Speak Old Parrot, gives plenty of evidence of how he came to be held in such high regard: witty and humane, subtle and skilful – I’d call him a national treasure if I wasn’t worried about upsetting the Welsh; so an international treasure.

Robin Robertson’s Hill of Doors shows him again to be one of the very best of a very strong generation of Scottish poets writing in these islands. The book’s reach is from the classical to the Renaissance and the contemporary, from high art and the tender to the brutal, from translation and international literature to the dark corners of disturbed individual hearts and minds. Within his tremendous range, Robertson has a terrific ear for variations in the music of languages and a perfect eye for detail. All his books are important events in our poetry and none more so than Hill of Doors.

Also international in its reach and significance is Daljit Nagra’s Ramayana. This utterly contemporary reimagining of an ancient epic often reminded me of Christopher Logue’s War Music in its drama and daring, but if anything takes more risks with language and history to bring something of an unfamiliar glory before contemporary audiences. Ramayana is a dazzling tour de force, returning our circle of consideration tonight to the Indian sub-continent after its world tour.

In all this, in poetry, as T. S. Eliot himself wrote in ‘East Coker’, ‘there is no competition’; not least because what poets do is so different, as must be obvious even from my brief comments here on these marvellous books, whose authors have set themselves unique challenges that they have all triumphantly met. However, we are here as fallible judges to award this year’s T. S. Eliot Prize to only one among the deserving, and we have given it to a brilliantly-faceted collection of wonderful formal variety and inventiveness, Sinéad Morrissey’s Parallax.

Ian Duhig, Chair of judges, announced the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 20213 in his speech at the Award Ceremony in the Wallace Collection on Monday 12 January 2014.

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘Sinéad Morrissey’s Parallax is also full of life observed in beautifully-turned language, many-angled and any-angled as her title suggests from, in her ‘Photographs of Belfast by Alexander Robert Hogg’ where she notes ‘each child strong enough / to manage it / carries a child’ through her own heritage as being the child of parents who were members of the Communist Party of Northern Ireland, to meditations on doctored photographs or ‘The Party Bazaar’, detritus from a time when the whole world seemed to be in one or the other of two armed camps.’ – Ian Duhig, Chair

I’d like to start by thanking all the poets we considered, on and off the shortlist, whose excellence demands that we honour them with events such as this, and I’d like to thank Chris Holifield and the Poetry Book Society for organising it and in particular my fellow judges, Imtiaz Dharker and Vicki Feaver, for making my very difficult task a pleasure with their intelligence, patience and insight.

Contemporary poetry is often criticised for being academic in all senses of that word: written for academics by academics and of no consequence to anyone but academics. British contemporary poetry in particular is criticised for its insularity, slow to reflect influences from elsewhere, even in the Anglosphere, for poetry in the English language has long been a global medium.

I believe the shortlist for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2013 is neither academic nor insular. Moniza Alvi‘s fine collection At the Time of Partition takes her poetic line for a walk like Klee’s but to pace out the birth of two nations, India and Pakistan, in a moving and powerful book that qualified it for inclusion on this shortlist even before this panel had to consider it by virtue of being a PBS Choice. This is a book that has already had an impact here and abroad, a very considerable work.

The partition of Ireland haunted the work of the late, great Seamus Heaney, a former winner of this Prize, whose voice in turn haunts the poetry of Maurice Riordan. His lush and wonderful collection The Water Stealer demonstrates his own mastery, though, for Maurice is one of the very best poets in these islands and this book shows him writing at the height of his powers. Both in his own poetry and in his work as an editor, now of The Poetry Review, Maurice’s approach is characterised by an internationalism in taste and imagination that all poets here are grateful for.

Helen Mort’s Division Street is one of the most celebrated English debuts of the new century, original and carefully-crafted, reflecting, among many other themes, the legacy of social division in this country, particularly to do with the Miners’ Strike of 1984-5, about which there continue to be revelations and scandals. The miner on the cover of her book in that famous photograph of an eyeballing confrontation is now dead, but Helen is vibrantly concerned with living and Division Street is full of life.

Sinéad Morrissey’s Parallax is also full of life observed in beautifully-turned language, many-angled and any-angled as her title suggests from, in her ‘Photographs of Belfast by Alexander Robert Hogg’ where she notes ‘each child strong enough / to manage it / carries a child’ through her own heritage as being the child of parents who were members of the Communist Party of Northern Ireland, to meditations on doctored photographs or ‘The Party Bazaar’, detritus from a time when the whole world seemed to be in one or the other of two armed camps.

PBS Choice and former winner of this Prize, George Szirtes is a child of those political binaries; born and brought up in a Hungary his family fled after the 1956 Uprising. His work as a translator has enriched all our poetry but as a poet himself, he is entirely original. In his book here, Bad Machine, we enjoy the fruits of his deep knowledge of art, George having trained as an artist, in many collaborations with other artists, giving us an inventive range of work taking in the Tottenham riots or Eddy Morganesque word music, as in his ‘Say So’.

Also a previous winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize and a PBS Choice, Anne Carson’s Red Doc>, continuing the story of her earlier Autobiography of Red in what is unquestionably one of the most fascinating books I have ever read of any description. A mixture of prose, poetry and the unclassifiable, when asked recently in an interview how she’d describe Red Doc> Anne answered: “I have no generic name for this farrago.” This seriously undersells a work of breathtaking originality.

PBS Choice Drysalter by Michael Symmons Roberts is already a double major prizewinner, having taken the Forward earlier in the season and the Costa Poetry Award only a week ago. In a book of wonderful beauty and subtlety, the first line from his poem ‘Through a Glass Darkly’, ‘Mist can be a form of mercy’ reminded me of Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows, which was described as ‘a hymn to nuance’. Hymns to nuance run through Drysalter, both profoundly spiritual and deeply rooted in this world and its capacity to sustain love.

Love is, perhaps, the most distinguishing feature of Dannie Abse‘s work both in terms of its subject matter and how it is received. I honestly cannot think of any writer who is held in greater affection than Dannie, and his new book on our shortlist, Speak Old Parrot, gives plenty of evidence of how he came to be held in such high regard: witty and humane, subtle and skilful – I’d call him a national treasure if I wasn’t worried about upsetting the Welsh; so an international treasure.

Robin Robertson’s Hill of Doors shows him again to be one of the very best of a very strong generation of Scottish poets writing in these islands. The book’s reach is from the classical to the Renaissance and the contemporary, from high art and the tender to the brutal, from translation and international literature to the dark corners of disturbed individual hearts and minds. Within his tremendous range, Robertson has a terrific ear for variations in the music of languages and a perfect eye for detail. All his books are important events in our poetry and none more so than Hill of Doors.

Also international in its reach and significance is Daljit Nagra’s Ramayana. This utterly contemporary reimagining of an ancient epic often reminded me of Christopher Logue’s War Music in its drama and daring, but if anything takes more risks with language and history to bring something of an unfamiliar glory before contemporary audiences. Ramayana is a dazzling tour de force, returning our circle of consideration tonight to the Indian sub-continent after its world tour.

In all this, in poetry, as T. S. Eliot himself wrote in ‘East Coker’, ‘there is no competition’; not least because what poets do is so different, as must be obvious even from my brief comments here on these marvellous books, whose authors have set themselves unique challenges that they have all triumphantly met. However, we are here as fallible judges to award this year’s T. S. Eliot Prize to only one among the deserving, and we have given it to a brilliantly-faceted collection of wonderful formal variety and inventiveness, Sinéad Morrissey’s Parallax.

Ian Duhig, Chair of judges, announced the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 20213 in his speech at the Award Ceremony in the Wallace Collection on Monday 12 January 2014.