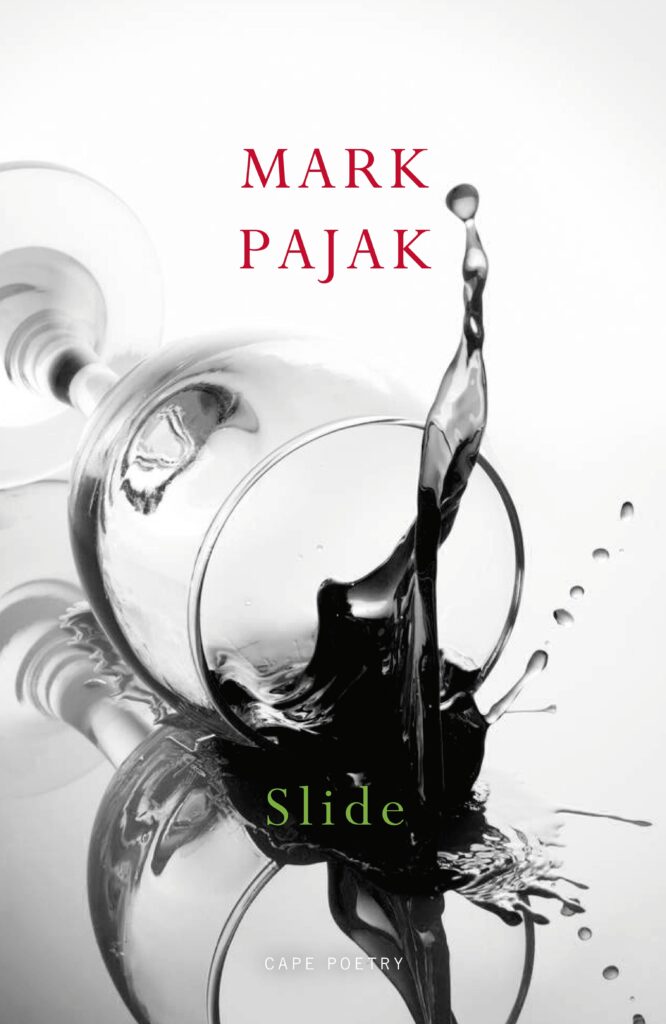

Mark Pajak was born in Merseyside in 1987 and currently lives in Scotland. His work has received a Northern Writers’ Award, a Society of Authors’ Grant, an Eric Gregory Award and a UNESCO international writing residency. He is a past recipient of the Bridport Prize and has three times been included in the National Poetry Competition winners list. Slide, Mark’s...

Review

Interview

Review

There’s something disquieting about the forensic quality of Slide, but Mark Pajak knows that by focusing on the surface he can leave us to plumb our own depths, writes John Field

Interview

‘For every one poem I feel is successful, there are an inordinate amount of failures behind it […] my process is glacial – it can feel like something akin to erosion’. We spoke to Mark Pajak about the making of Slide (Cape Poetry, 2022), his Eliot Prize-shortlisted collection

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

Mark Pajak reads from Slide at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Eric Yip reviews Mark Pajak’s Slide

Mark Pajak talks about his work

Mark Pajak reads ‘Reset’

Mark Pajak reads ‘Crystal’

Mark Pajak reads ‘Thin’

Related News Stories

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2022 is Anthony Joseph for his collection Sonnets for Albert published by Bloomsbury Poetry.

The T. S. Eliot Prize and The Poetry Society have now published the first set of video reviews created by participants in the new Young Critics Scheme.

Judges Jean Sprackland (Chair), Hannah Lowe and Roger Robinson have chosen the 2022 T. S. Eliot Prize shortlist from a record 201 poetry collections submitted by British and Irish publishers. The eclectic list comprises seasoned poets, including one previous winner, and five debut collections. Victoria Adukwei Bulley – Quiet (Faber &...