Born in London to English and Jamaican parents, Karen McCarthy Woolf FRSL is the author of three poetry books and the editor of numerous literary anthologies. As a postdoctoral Fulbright Scholar at UCLA, she was writer in residence at the Promise Institute for Human Rights. Her debut An Aviary of Small Birds (Carcanet Press, 2014), was an Observer Book of...

Review

Review

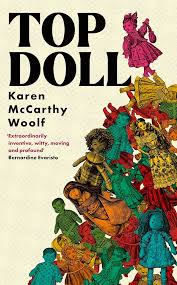

Karen McCarthy Woolf's Top Doll is a bravura, polyphonic exploration of obsession, mortality and an unflinching look at the history of slavery in America, writes John Field

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

Karen McCarthy Woolf reads from Top Doll at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Karen McCarthy Woolf talks about her work

Karen McCarthy Woolf reads from ‘Dolly’

Karen McCarthy Woolf reads ‘The General’

Karen McCarthy Woolf reads ‘Babysitter Barbie’

Young Critic Priya Abularach reviews Karen McCarthy Woolf’s Top Doll

Related News Stories

There was a brilliant response to the T. S. Eliot Prize 2024 Shortlist Readings, held at the Royal Festival Hall, London, on 12 January 2025. Each of the ten shortlisted poets, including Karen McCarthy Woolf (shown above) gave extraordinary readings at what is the largest annual poetry event in the...

McCarthy Woolf has […] breathed new life into this well-worn trope (Mannequin, Toy Story… erm Chucky), adding poignancy to the book’s “stranger than fiction” tale of a heiress who preferred dolls to people.’ – Yvonne Singh, Writers Mosaic Karen McCarthy Woolf, shortlisted for Top Doll (Dialogue Books, 2024), is the...

The T.S. Eliot Prize and The Poetry Society are excited to share the second set of video reviews created as part of the Young Critics Scheme. ‘Their inventiveness and attention to poetic detail is always such a delight’, writes Cia Mangat of The Poetry Society, on the Children’s Poetry Summit...

We are thrilled to announce the T. S. Eliot Prize 2024 Shortlist, chosen by judges Mimi Khalvati (Chair), Anthony Joseph and Hannah Sullivan from 187 poetry collections submitted by British and Irish publishers. The eclectic list comprises seasoned poets, two debuts, two second collections, and two previously shortlisted poets from...