Kevin Young was born in Lincoln, Nebraska and now lives in New York. He is the author of fifteen books of poetry and prose, including Brown; Blue Laws: Selected & Uncollected Poems 1995-2015; Book of Hours, winner of the Lenore Marshall Prize from the Academy of American Poets; Jelly Roll: a blues, a finalist for both the National Book Award...

Review

Review

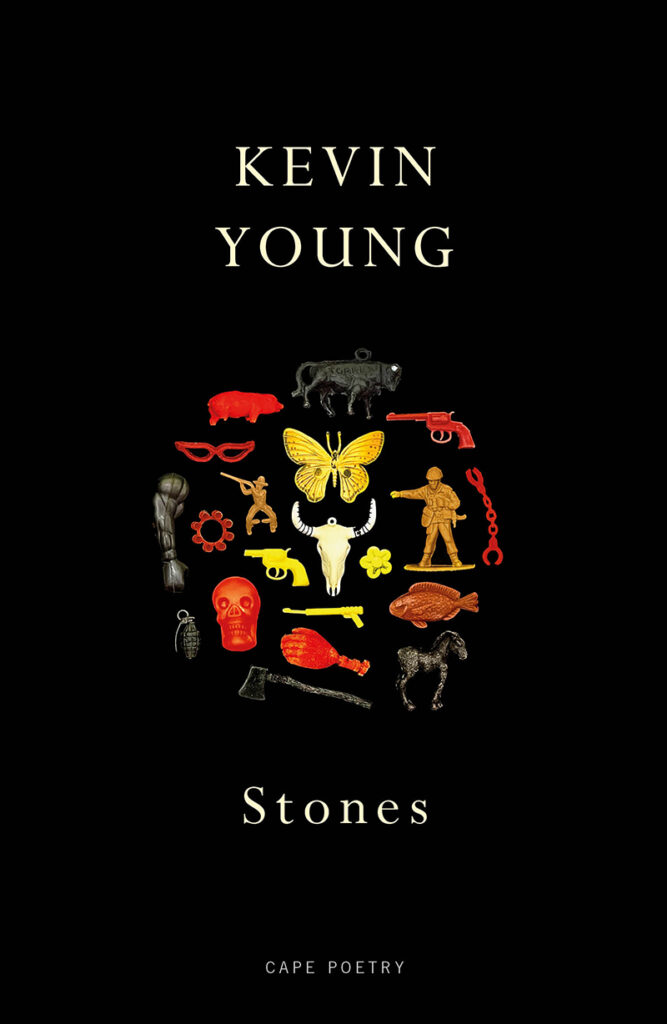

Kevin Young’s Stones is a hymn to the dearly departed. Resisting that timeless human urge to aggrandise the dead, his humble memorial creates something far more affecting, writes John Field

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

Kevin Young reads from Stones at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Kevin Young talks about his work

Kevin Young reads ‘Lillies’

Kevin Young reads ‘Egrets’

Kevin Young reads ‘Russet’

Kevin Young reads ‘Sandy Road’

Related News Stories

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2021 is Joelle Taylor for C+nto & Othered Poems, published by The Westbourne Press. Chair Glyn Maxwell said: Every book on the Shortlist had a strong claim on the award. We found...

Judges Glyn Maxwell (Chair), Caroline Bird and Zaffar Kunial have chosen the T. S. Eliot Prize 2021 Shortlist from a record 177 poetry collections submitted by British and Irish publishers. The Shortlist consists of an eclectic mixture of established poets, none of whom has previously won the Prize, and...

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce the judges for the 2021 Prize. The panel will be chaired by Glyn Maxwell, alongside Caroline Bird and Zaffar Kunial. The 2021 judging panel will be looking for the best new poetry collection written in English and published in 2021. The...