Katrina Porteous was born in Aberdeen and has lived on the Northumberland coast since 1987. Many of the poems in her first collection, The Lost Music (Bloodaxe Books,1996), explore the Northumbrian fishing community. Her second, Two Countries (Bloodaxe Books, 2014), was shortlisted for the Portico Prize for Literature in 2015. Edge (Bloodaxe Books, 2019) draws on collaborations commissioned for performance...

Review

Review

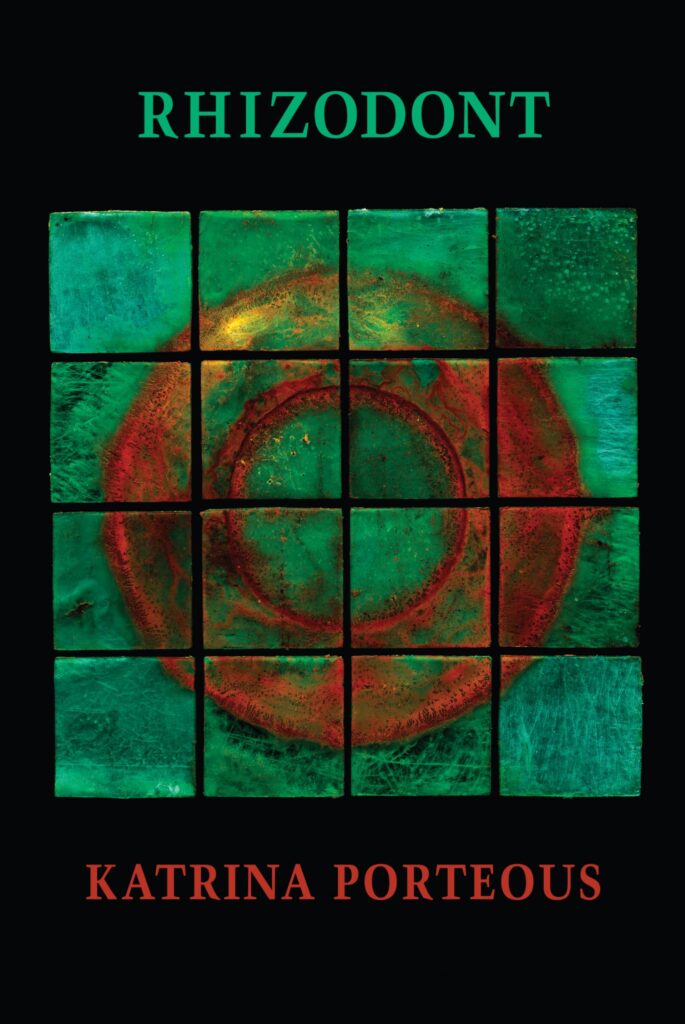

John Field finds Katrina Porteous’s Rhizodont to be ‘a thrilling meeting of ideas and language’, blurring ‘the boundary between man and machine, between planet and technology.’

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

Katrina Porteous reads from Rhizodont at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Young Critic Tusshara Nalakumar Srilatha reviews Katrina Porteous’s Rhizodont

Katrina Porteous talks about her work

Katrina Porteous reads ‘#rhizodont’

Katrina Porteous reads ‘Coastal Erosion’

Katrina Porteous reads ‘Antarctica Without its Ice’

Related News Stories

There was a brilliant response to the T. S. Eliot Prize 2024 Shortlist Readings, held at the Royal Festival Hall, London, on 12 January 2025. Each of the ten shortlisted poets, including Karen McCarthy Woolf (shown above) gave extraordinary readings at what is the largest annual poetry event in the...

The T.S. Eliot Prize and The Poetry Society are excited to share the second set of video reviews created as part of the Young Critics Scheme. ‘Their inventiveness and attention to poetic detail is always such a delight’, writes Cia Mangat of The Poetry Society, on the Children’s Poetry Summit...

Katrina Porteous, shortlisted with her collection Rhizodont (Bloodaxe Books, 2024), is the featured poet in this week’s Eliot Prize e-newsletter. The newsletter tells you about the wide range of content we have just published to help you get to know Katrina and her work. This includes specially produced videos of...

We are thrilled to announce the T. S. Eliot Prize 2024 Shortlist, chosen by judges Mimi Khalvati (Chair), Anthony Joseph and Hannah Sullivan from 187 poetry collections submitted by British and Irish publishers. The eclectic list comprises seasoned poets, two debuts, two second collections, and two previously shortlisted poets from...