Will Harris is a writer of Chinese Indonesian and British heritage, born and based in London. His poetry pamphlet, All this is implied (HappenStance 2017), was joint winner of the London Review Bookshop Pamphlet of the Year and shortlisted for the Callum Macdonald Memorial Award. His poems and essays have been published in the TLS, Granta, the Guardian, and the London Review of Books, and...

Review

Review

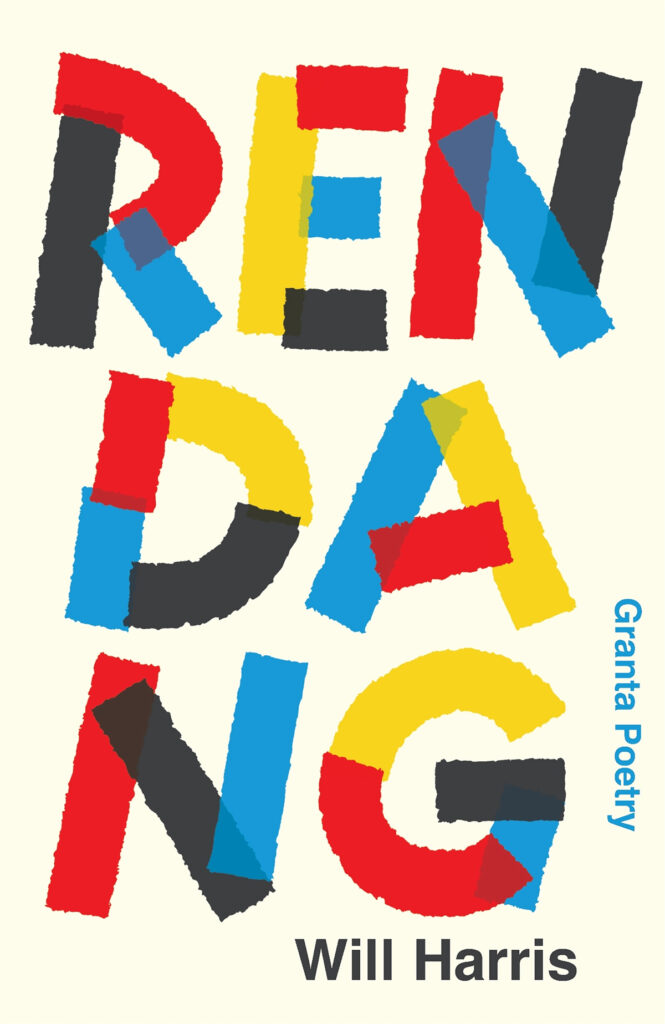

In Will Harris's RENDANG, meaning is evasive and possibilities ripple through poems as Harris shows us the irresistible, distorting force of presumption and cultural heritage, writes John Field

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

Will Harris talks about his work

Will Harris reads ‘Scene Change’

Will Harris reads ‘The White Jumper’

Related News Stories

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2020 is Bhanu Kapil for How to Wash a Heart, published by Pavilion Poetry (Liverpool University Press). Chair Lavinia Greenlaw said: Our Shortlist celebrated the ways in which poetry is responding to...

‘The list really began through these poets’ trust in me’ – Rachael Allen I am very inspired by a number of presses in North America, including WAVE books, Ugly Duckling Presse and Black Ocean, and the way these presses (and others like them) create space for erudite, visually innovative, essential...

Judges Lavinia Greenlaw (Chair), Mona Arshi and Andrew McMillan have chosen the 2020 T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist from 153 poetry collections submitted by British and Irish publishers. The shortlist comprises work from five men and five women; two Americans; as well as poets of Native American, Chinese Indonesian and...

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce the judges for the 2020 Prize. The panel will be chaired by Lavinia Greenlaw, alongside Mona Arshi and Andrew McMillan. The 2020 judging panel will be looking for the best new poetry collection written in English and published in 2020. The...