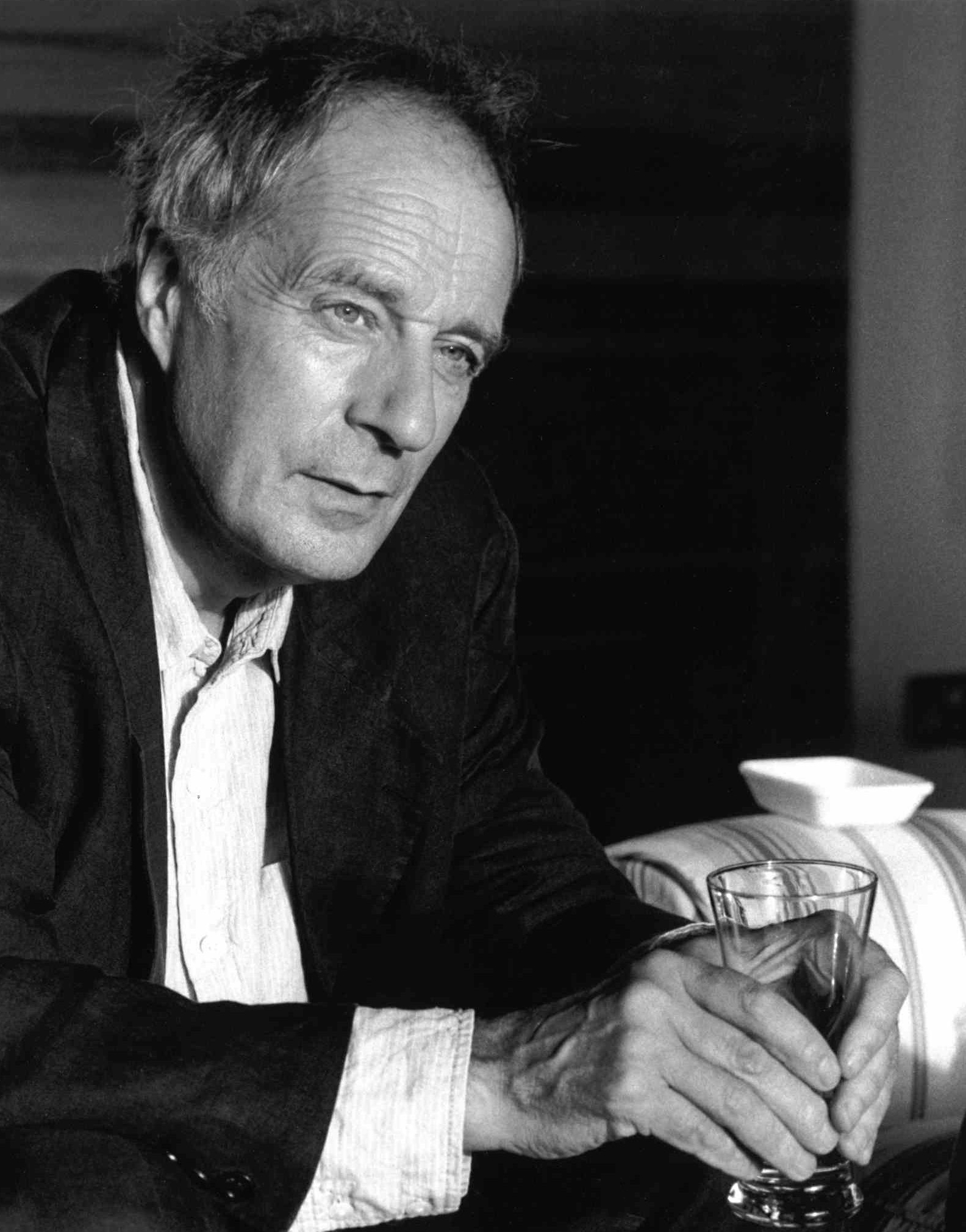

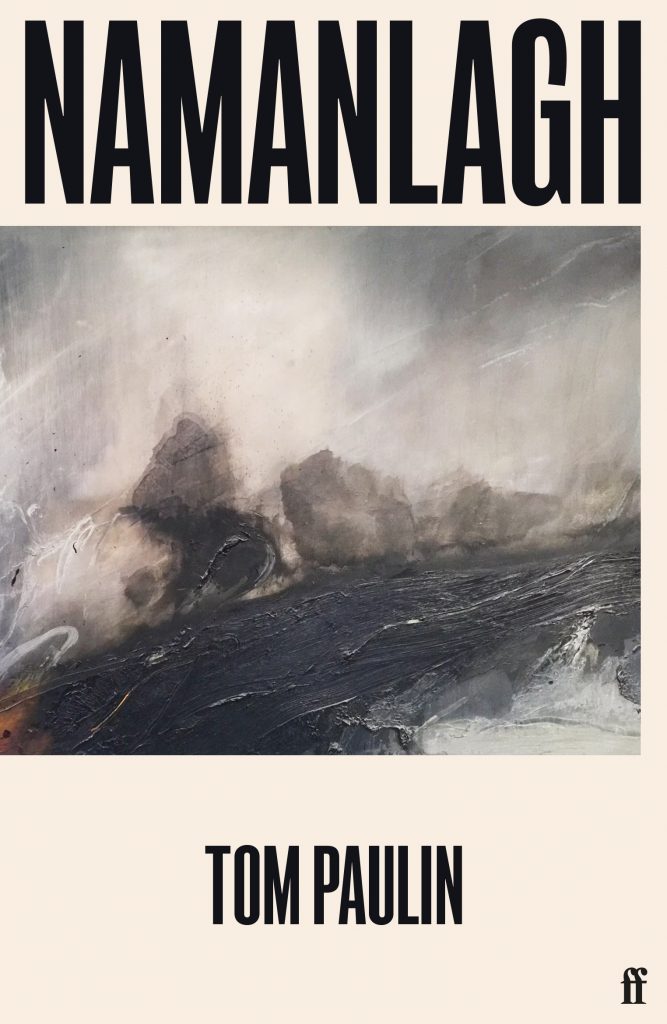

Tom Paulin grew up in Belfast and now lives in Oxford, where he is Emeritus Fellow of Hertford College, University of Oxford. Namanlagh (Faber & Faber), his first collection in a decade, is his tenth book of poetry and was recently awarded the PEN Heaney Prize 2025, as well as being shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2025. Of...

Review

Review

In Tom Paulin’s Namanlagh, the past lives on in the memory: tactile, vivid and immediate, writes John Field

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

Jamie McKendrick reads Tom Paulin’s poem ‘The 8th Army Cemetery, El Alamein’

Bernard O’Donoghue reads Tom Paulin’s poem ‘Quand vous serez bien vieille’

On Tom Paulin’s ‘Namanlagh’ – Jamie McKendrick & Bernard O’Donoghue

Tom Paulin reads his poem ‘Namanlagh’

Tom Paulin reads his poem ‘Folly Bridge’

Related News Stories

Tom Paulin, shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2025 with his collection Namanlagh (Faber & Faber), is the featured poet in this week’s Eliot Prize newsletter. The newsletter tells you about the wide range of content we have just published to help you get to know Tom and his...

We’re delighted to announce the T. S. Eliot Prize 2025 Shortlist, which offers ‘something for everyone’ in collections of ‘great range, suggestiveness and power’. Judges Michael Hofmann (Chair), Patience Agbabi and Niall Campbell chose the Shortlist from 177 poetry collections submitted by 64 British and Irish publishers. The diverse list...

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce the judges for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2025. Chair Michael Hofmann will be joined on the panel by Patience Agbabi and Niall Campbell. Michael Hofmann said: I’m delighted to be asked to judge the T. S. Eliot Prize and look...