Deryn Rees-Jones was born in Liverpool with family links to North Wales. Her poetry collections (all Seren) are The Memory Tray (1995), Signs Round a Dead Body (1998), Quiver (2004) and Burying the Wren (2012), which was a Poetry Book Society Recommendation and shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize. Erato (2019) was also a PBS Recommendation, and shortlisted for...

Review

Review

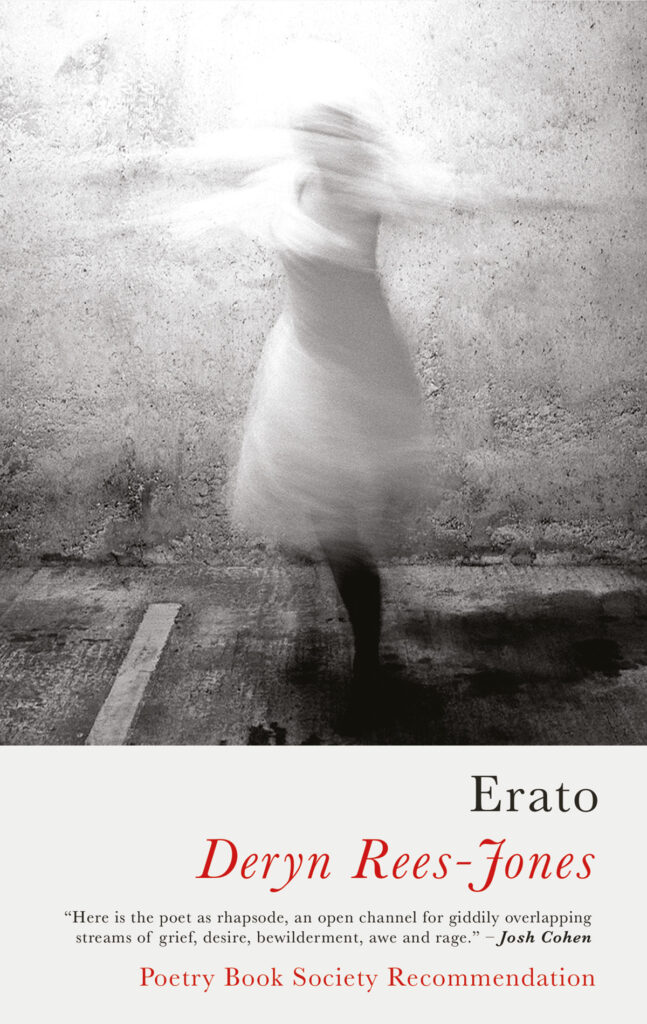

The shapeshifting quality of Deryn Rees-Jones's Erato, its exploration of mistakes, distortions, the destructive and the fantastical, make it a virtuosic and devastating collection, writes John Field

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

Deryn Rees-Jones reads from Erato at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Deryn Rees-Jones talks about her work

Deryn Rees-Jones reads ‘Gardens’

Deryn Rees-Jones reads ‘Heartbreak’

Deryn Rees-Jones reads ‘Mon Amour’

Related News Stories

Roger Robinson has won the T. S. Eliot Prize 2019 with his searing collection A Portable Paradise, published by Peepal Tree Press. After months of reading and deliberation, judges John Burnside, Sarah Howe and Nick Makoha unanimously chose the winner from a Shortlist which comprised five men, four women and...

This year sees the 27th T. S. Eliot Prize being awarded, and the roster of past winners includes some very well-known poets alongside some lesser known authors that demand further attention. To refresh the memory of prizes past, the T. S. Eliot Prize website contains a trove of information on...

Judges John Burnside (Chair), Sarah Howe and Nick Makoha have chosen the T. S. Eliot Prize 2019 Shortlist from 158 poetry collections submitted by British and Irish publishers. Featuring new voices and veteran poets, and covering an extraordinary range of themes, the Shortlist comprises five men, four women and one...