James Conor Patterson is from Newry in the north of Ireland and currently lives in London. He won an Eric Gregory Award for bandit country in 2019 and fragments and versions of the poems appeared in publications including Magma, The Moth, New Statesman, Poetry Ireland Review, The Poetry Review, The Stinging Fly, Poetry London and The Tangerine. A selection of...

Review

Interview

Review

In bandit country, James Conor Patterson writes of Newry as a place of the future while acknowledging the power of the past and its ability to menace the present, writes John Field

Interview

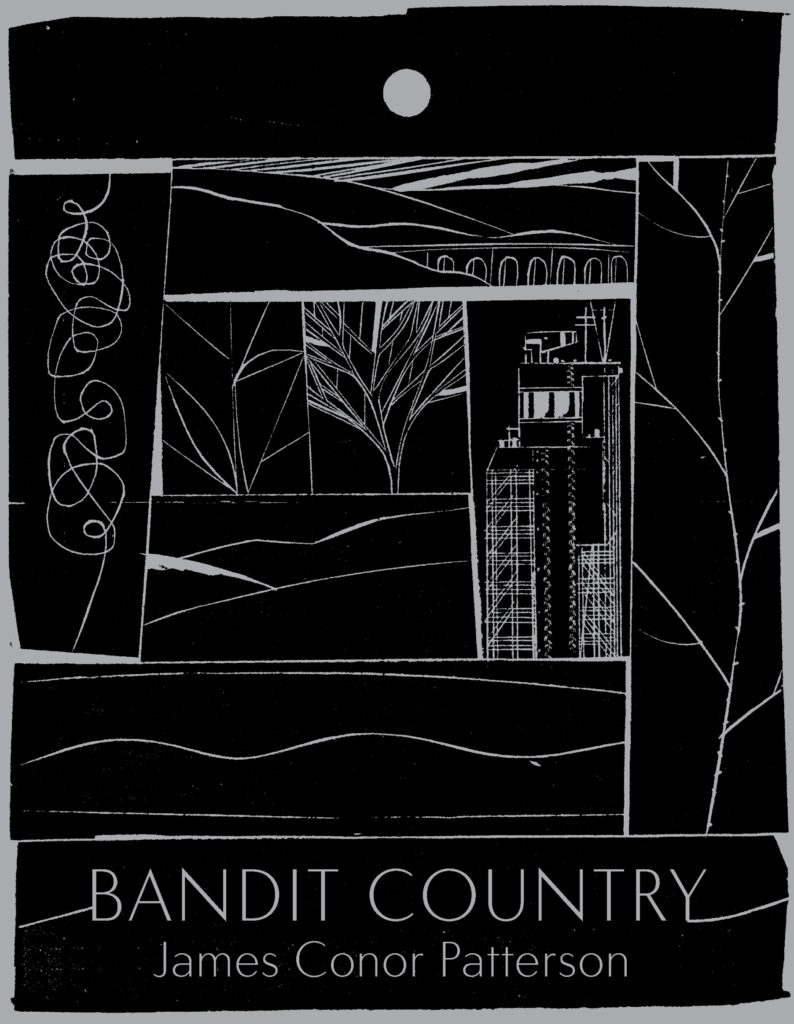

James Conor Patterson is shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2022 for his debut collection, bandit country (Picador Poetry, 2022). We asked him about dialect and sense of place, politics, humour and liberation

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

James Conor Patterson reads from bandit country at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Lily McDermott reviews James Conor Patterson’s bandit country

James Conor Patterson reads ‘london mixtape’

James Conor Patterson reads ‘yew’

James Conor Patterson talks about his work

James Conor Patterson reads ‘the drowning’

Related News Stories

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2022 is Anthony Joseph for his collection Sonnets for Albert published by Bloomsbury Poetry.

Judges Jean Sprackland (Chair), Hannah Lowe and Roger Robinson have chosen the 2022 T. S. Eliot Prize shortlist from a record 201 poetry collections submitted by British and Irish publishers. The eclectic list comprises seasoned poets, including one previous winner, and five debut collections. Victoria Adukwei Bulley – Quiet (Faber &...