2021

T. S. Eliot Prize

Winner

The Chair of the judges’ speech

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘When you read any poetry book, delight in it and afford it deep consideration, it becomes a kind of house on the hill. When you’re not reading it, its lights are still glowing in the windows, or figures pass by in silhouette; when you are reading it, you’re there inside, breathing its familiar air, sharing its extraordinary vantage points. Either way you know those houses, you love them, you feel an unsettling fond intimacy with them.’ – Glyn Maxwell, Chair

Ten Houses On A Hill: words on the shortlisted books, T.S. Eliot Prize 2021 – the Chair of judges’ speech by Glyn Maxwell

When you read any poetry book, delight in it and afford it deep consideration, it becomes a kind of house on the hill. When you’re not reading it, its lights are still glowing in the windows, or figures pass by in silhouette; when you are reading it, you’re there inside, breathing its familiar air, sharing its extraordinary vantage points. Either way you know those houses, you love them, you feel an unsettling fond intimacy with them.

I think the time of lockdown has amplified this feeling. So I make no apology for looking up at these ten magnificent houses on the hill with the first-name familiarity of a soul locked down too long, still emerging with childlike relief from under that dismal spell, amazed by the light that’s spilling from the windows.

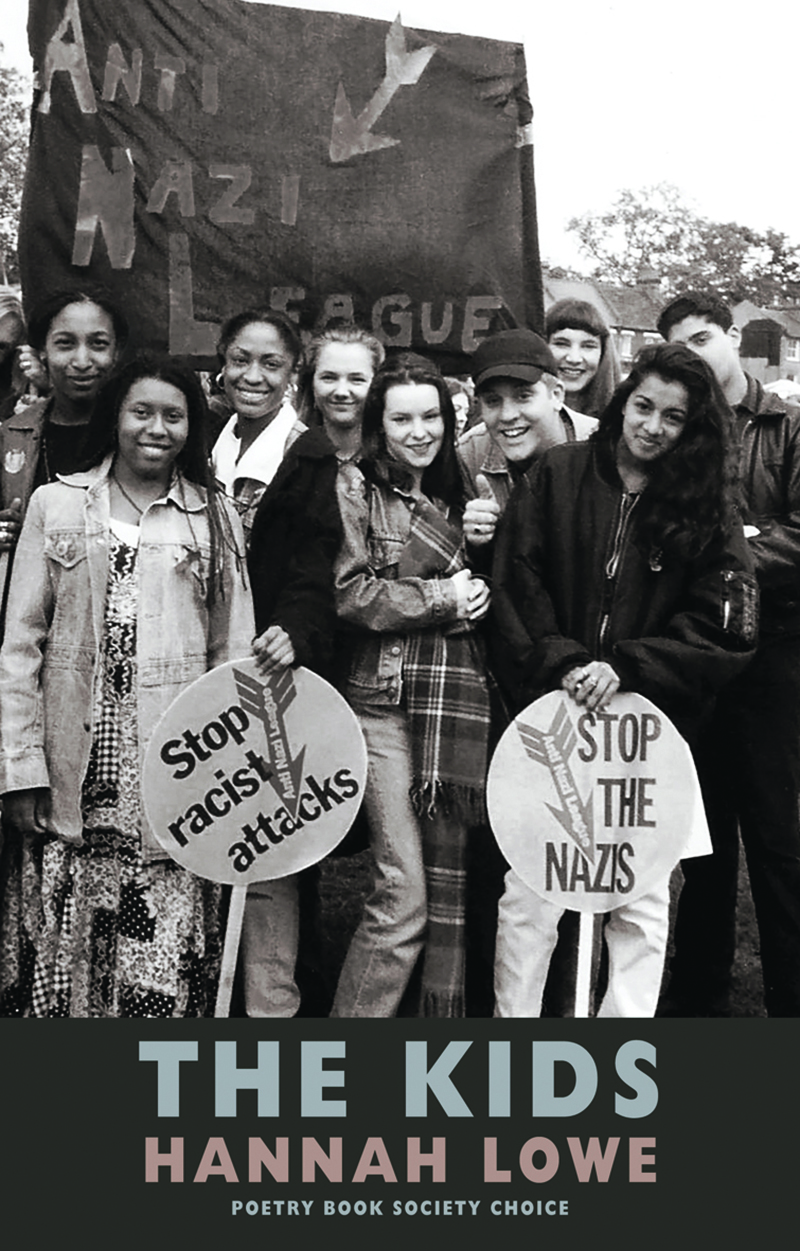

Hannah’s House is full of the young, their teenage years the length of sonnets, you follow passageways towards their noise but when you open the door you may not find them, you may find one of them years later, you may find the poet herself sitting alone in the past or the future. Either way in a blessed school of learning.

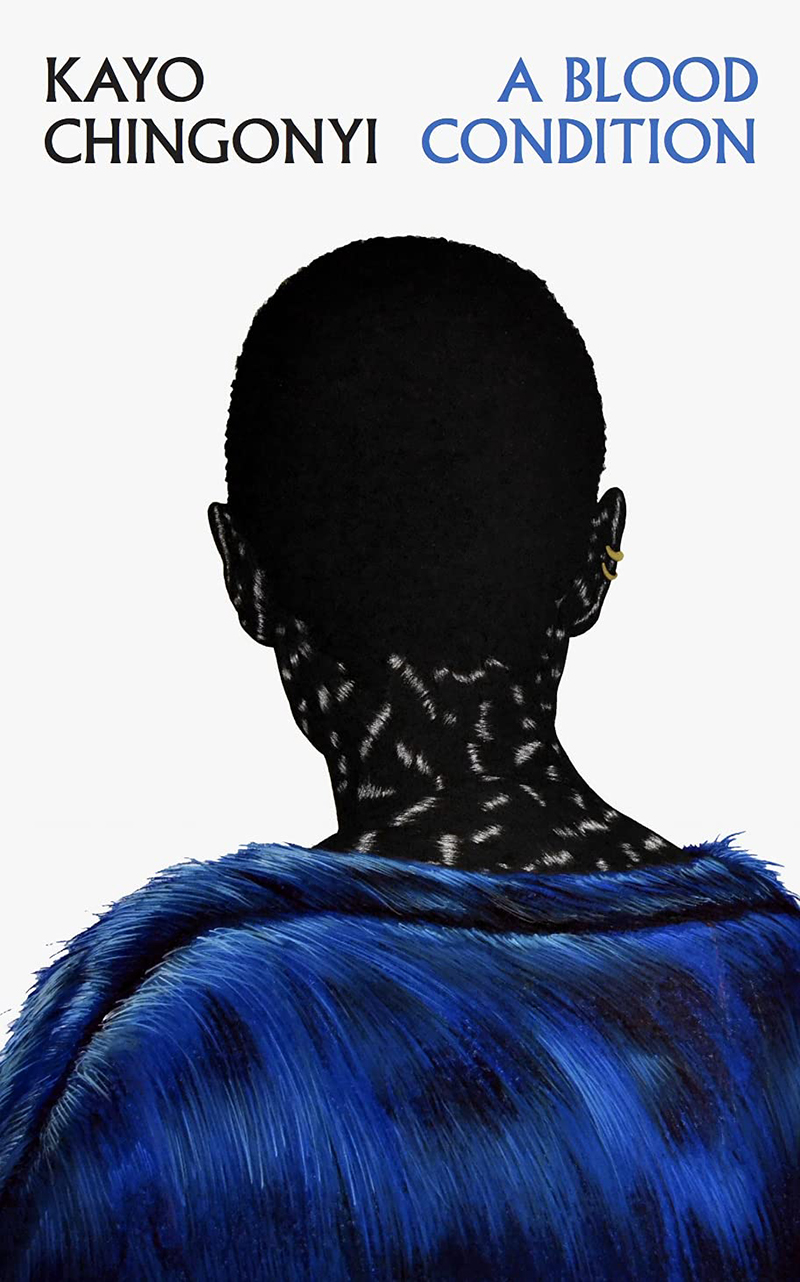

Kayo’s House is full of music, even its silences are full of music, and every room you pass through has a second door to somewhere else. Villages give way to cities, cities to the rooms of childhood, and all the while a great wide river is flowing along beside you When you close the last door you hear only pulse and breath and they too are like music.

From Michael’s House you watch from behind curtains, it might be dangerous to be seen. You watch the menacing outlines of stories unfolding down there in the town, old tales that can’t be stopped, fleeting fugitives you can neither rescue nor redeem. When you turn back into the room you can’t forget what you just saw.

Jack’s House is labyrinthine, every door leads somewhere. One minute it’s a doll’s house and don’t wake the baby, next minute it’s a whole world run by the infantile. Fresh light blinks and dazzles as you cross each room, or you just stand there brimming with what you’re being shown. There’s one room you’ll never leave.

Kevin’s House is like the Brontë house, there are graveyards on two sides. But these graveyards are also gardens. The deep rewarded faith in those tercets moves us from stone to stone, flower to flower, memory to memory, and in each poem the air slowly darkens, deepens and weighs more, like any afternoon on earth.

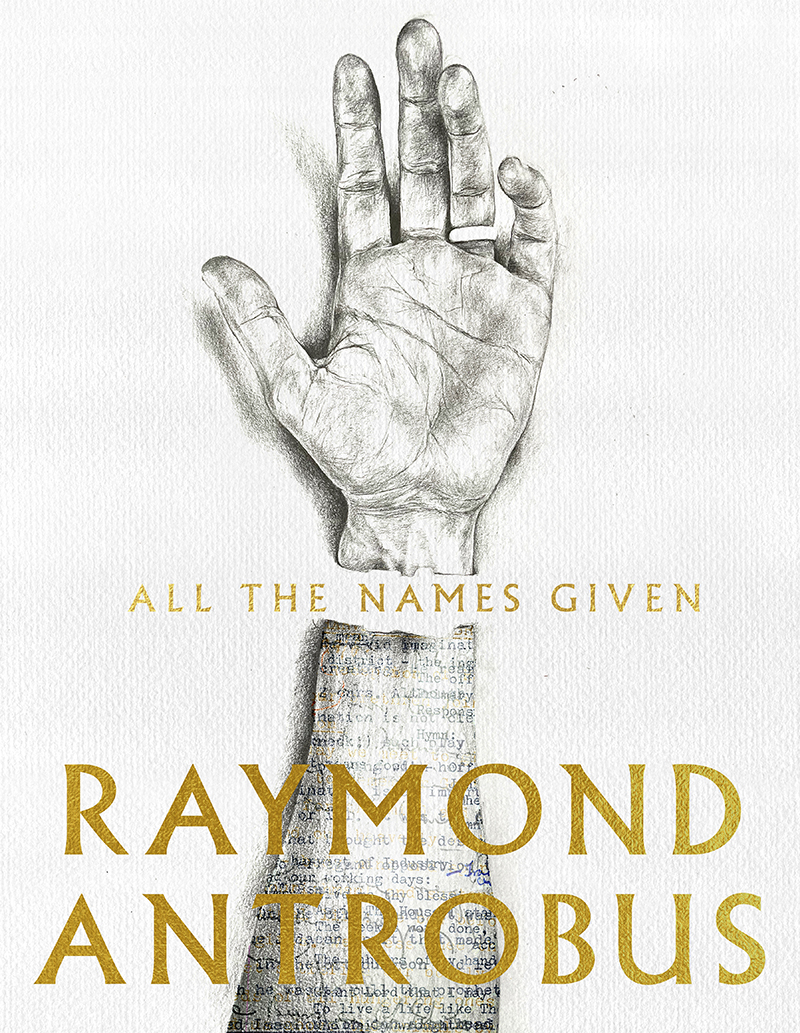

Raymond’s House has his name above the door, and you follow it up and down staircases and spirals, to galleries and crypts, guided between them by stage-directions for the ages. The lost and the loved and the long-gone share dusty indelible rooms, but out through the open window? – sunlight on all your fields.

At Victoria’s House – don’t look in the fridge. In fact do look there, and look everywhere else. She will guide you past portraits whose eyes go with you, guide you past dead bodies and tell you to keep moving, guide you in and out of adulthood, teenage, childhood, and if you get out alive you’ll be bleeding with light.

There’s a Treasure Hunt going on in Selima’s Cottage. I say cottage but it’s infinite in size, there’s a clue on every mantelpiece, under every ornament, falling out of yellow old books and cutlery drawers. Everything points somewhere, and when you solve it all, mister, you don’t get a prize. Because it’s all just pointing at you.

In Joelle’s House the walls ring with rage and light at what was done here, what was not done, what was traduced or barred or neglected. When the rage sings and the light flashes it catches the faces of four angels in their glad-rags. Their brilliant clear gospel carries to every room, which means it carries over the fields to everywhere.

Daniel’s House isn’t even a metaphor, in fact it’s not even a House it’s a Room, but it’s the Room where they keep everything. The air trembles with it all. You’re reminded that the only rooms that matter in life are those where you’re on your own with love. Out of enduring suffering they have made you a chapel.

One more thing. And this is to the nine extraordinary poets about to not win this prize. First, I would have you remember what Eliot wrote in Tradition and the Individual Talent:

The existing monuments form an ideal order among themselves, which is modified by the introduction of the new work of art among them. The existing order is complete before the new work arrives; for order to persist after the supervention of novelty, the whole existing order must be, if ever so slightly, altered…

This is the work you do. And, to let Mr Auden gatecrash an Eliot night – as I always like to do – in a time where we are all beleaguered with negation and despair, your books, your houses on the hill, show an affirming flame, you are each an affirming flame, people flock and have flocked and will flock to your light. These lights have to burn brighter than ever now. Caroline and Zaffar and I also carry them within us, so for that you have our profound gratitude.

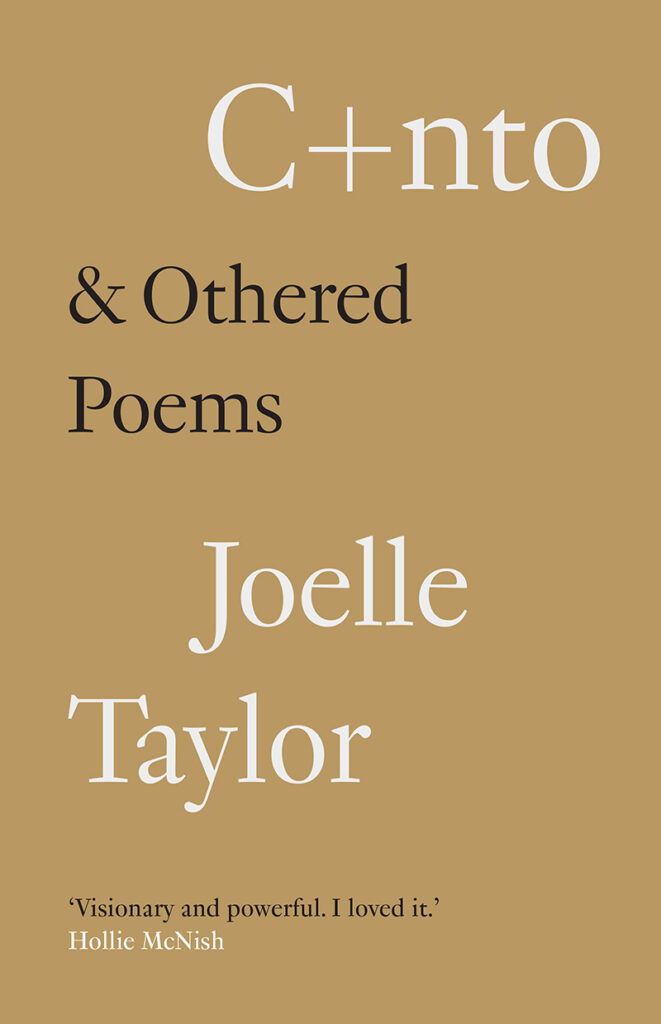

The winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2021 is Joelle Taylor for Cunto & Othered Poems.

This speech was given at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2021 Award Ceremony at the Wallace Collection, London, on 10 January 2022.

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘When you read any poetry book, delight in it and afford it deep consideration, it becomes a kind of house on the hill. When you’re not reading it, its lights are still glowing in the windows, or figures pass by in silhouette; when you are reading it, you’re there inside, breathing its familiar air, sharing its extraordinary vantage points. Either way you know those houses, you love them, you feel an unsettling fond intimacy with them.’ – Glyn Maxwell, Chair

Ten Houses On A Hill: words on the shortlisted books, T.S. Eliot Prize 2021 – the Chair of judges’ speech by Glyn Maxwell

When you read any poetry book, delight in it and afford it deep consideration, it becomes a kind of house on the hill. When you’re not reading it, its lights are still glowing in the windows, or figures pass by in silhouette; when you are reading it, you’re there inside, breathing its familiar air, sharing its extraordinary vantage points. Either way you know those houses, you love them, you feel an unsettling fond intimacy with them.

I think the time of lockdown has amplified this feeling. So I make no apology for looking up at these ten magnificent houses on the hill with the first-name familiarity of a soul locked down too long, still emerging with childlike relief from under that dismal spell, amazed by the light that’s spilling from the windows.

Hannah’s House is full of the young, their teenage years the length of sonnets, you follow passageways towards their noise but when you open the door you may not find them, you may find one of them years later, you may find the poet herself sitting alone in the past or the future. Either way in a blessed school of learning.

Kayo’s House is full of music, even its silences are full of music, and every room you pass through has a second door to somewhere else. Villages give way to cities, cities to the rooms of childhood, and all the while a great wide river is flowing along beside you When you close the last door you hear only pulse and breath and they too are like music.

From Michael’s House you watch from behind curtains, it might be dangerous to be seen. You watch the menacing outlines of stories unfolding down there in the town, old tales that can’t be stopped, fleeting fugitives you can neither rescue nor redeem. When you turn back into the room you can’t forget what you just saw.

Jack’s House is labyrinthine, every door leads somewhere. One minute it’s a doll’s house and don’t wake the baby, next minute it’s a whole world run by the infantile. Fresh light blinks and dazzles as you cross each room, or you just stand there brimming with what you’re being shown. There’s one room you’ll never leave.

Kevin’s House is like the Brontë house, there are graveyards on two sides. But these graveyards are also gardens. The deep rewarded faith in those tercets moves us from stone to stone, flower to flower, memory to memory, and in each poem the air slowly darkens, deepens and weighs more, like any afternoon on earth.

Raymond’s House has his name above the door, and you follow it up and down staircases and spirals, to galleries and crypts, guided between them by stage-directions for the ages. The lost and the loved and the long-gone share dusty indelible rooms, but out through the open window? – sunlight on all your fields.

At Victoria’s House – don’t look in the fridge. In fact do look there, and look everywhere else. She will guide you past portraits whose eyes go with you, guide you past dead bodies and tell you to keep moving, guide you in and out of adulthood, teenage, childhood, and if you get out alive you’ll be bleeding with light.

There’s a Treasure Hunt going on in Selima’s Cottage. I say cottage but it’s infinite in size, there’s a clue on every mantelpiece, under every ornament, falling out of yellow old books and cutlery drawers. Everything points somewhere, and when you solve it all, mister, you don’t get a prize. Because it’s all just pointing at you.

In Joelle’s House the walls ring with rage and light at what was done here, what was not done, what was traduced or barred or neglected. When the rage sings and the light flashes it catches the faces of four angels in their glad-rags. Their brilliant clear gospel carries to every room, which means it carries over the fields to everywhere.

Daniel’s House isn’t even a metaphor, in fact it’s not even a House it’s a Room, but it’s the Room where they keep everything. The air trembles with it all. You’re reminded that the only rooms that matter in life are those where you’re on your own with love. Out of enduring suffering they have made you a chapel.

One more thing. And this is to the nine extraordinary poets about to not win this prize. First, I would have you remember what Eliot wrote in Tradition and the Individual Talent:

The existing monuments form an ideal order among themselves, which is modified by the introduction of the new work of art among them. The existing order is complete before the new work arrives; for order to persist after the supervention of novelty, the whole existing order must be, if ever so slightly, altered…

This is the work you do. And, to let Mr Auden gatecrash an Eliot night – as I always like to do – in a time where we are all beleaguered with negation and despair, your books, your houses on the hill, show an affirming flame, you are each an affirming flame, people flock and have flocked and will flock to your light. These lights have to burn brighter than ever now. Caroline and Zaffar and I also carry them within us, so for that you have our profound gratitude.

The winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2021 is Joelle Taylor for Cunto & Othered Poems.

This speech was given at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2021 Award Ceremony at the Wallace Collection, London, on 10 January 2022.