2017

T. S. Eliot Prize

Winner

The Chair of the judges’ speech

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘Judging the Eliot is a strange, strangely delightful duty. You are required to go beyond your taste, and yet not to lose touch with it; to read in good faith, while acknowledging your obvious limitations; and, finally, to commit to an agreement by committee about that at which most individuals would baulk: that a single book of poems can be ‘the best’. You get to disappoint scores of poets, in order to celebrate, not a few, not even that one book, but the art itself.’ – W. N. Herbert, Chair

T. S. Eliot Prize 2017: the Chair of judges’ speech by W. N. Herbert

Judging the Eliot is a strange, strangely delightful duty. You are required to go beyond your taste, and yet not to lose touch with it; to read in good faith, while acknowledging your obvious limitations; and, finally, to commit to an agreement by committee about that at which most individuals would baulk: that a single book of poems can be ‘the best’. You get to disappoint scores of poets, in order to celebrate, not a few, not even that one book, but the art itself.

Most importantly, you get, for a few dizzying moments, the delight of holding a whole year of poetry in your head. And what a year – over 150 collections! Our longlists were packed with strong contenders, and even our individual shortlists were more various than the number ten could handle – 25 would’ve been more like it. In short, it was not a lean year, and in the ten we selected we found richness and variety of voice, theme, and form, sustained, not just through a brilliant handful of poems or a galvanising sequence, but, marvellously, across entire collections.

Here is a brief alphabetic summation.

Tara Bergin’s The Tragic Death of Eleanor Marx explores the relationship between dominant narratives and those who attempt to interpret or embody them, moving from its titular suicide through translations of Flaubert, stage directions in Strindberg, jargon in academia, and the grim logic of fairy tales. Hers is an original voice of great power that flicks between speech and song, and between the borrowed and the wholly owned, with consummate ease.

‘I want a different kind of pain. / If I can get it once / I won’t come back again.’

Caroline Bird’s In These Days of Prohibition is equally pleasurable and disturbing, because it understands the genuinely strange ground on which we must build our thoughts and our emotions. In work of great and frequently comic poise it captures moments of absolute loss of control, and absolute freedom. We recognise that sustained unsettling comic virtuosity is the startling agent by which we engage with such loss, such freedom.

‘In the ambulance I turned to you and said, // “Don’t worry baby, I’ve got this.”’

Douglas Dunn’s The Noise of a Fly marks a triumphant return after sixteen years. It is rare to read work reflecting on ageing with such wit and formal mastery, riffing on major themes from throughout his career and resting on the possible secular communion with place, namely Fife, as a sort of poetic terroir. This is, as Dunn hints in his poem on two self-portraits by Rembrandt, the rich late period of an old master: wry, sensuous, utterly unsentimental.

‘Whatever I do is a robin’s prayer.’

Leontia Flynn’s The Radio sees one of Northern Ireland’s most assured voices continue her engagement with the alchemy of form in an effortlessly contemporary manner, indeed driving the thought thrillingly through longer stanza forms, including a brilliant elegy for Heaney. The exposure of family, and its intimate matrix of the generations, to the equal threats of history and human frailty is played out in work with an intense sense of place and moment.

‘the faint persistent hum of the first Real Thing.’

Roddy Lumsden’s So Glad I’m Me is fully fluent in its own unique English, in which the everyday and the elegiac and the elliptical are mashed together into a rich music. Thanks to this command of phrase, his intense savouring of the minutiae of relationship, food, and song achieves a delirious democracy of the senses and the intellect. This is poetry which manages to survive in those fragmentary glimpses of our lives and our other, potential lives, and realises –

‘Everything has something to do with love.’

Robert Minhinnick’s Diary of the Last Man casts a ferocious eye on the natural world’s vulnerabilities – and our own – in the dysfunctional relationship we have created with that world. His is an apocalyptic vision which moves from isolated contemplation of the fragile beauties of place, most usually South Wales, through atrocity in Iraq, to a community of translations from the Turkish, Arabic and Welsh, achieving a bleakly affirming global regard.

‘Yes this is what happens / when the old men make us wait’

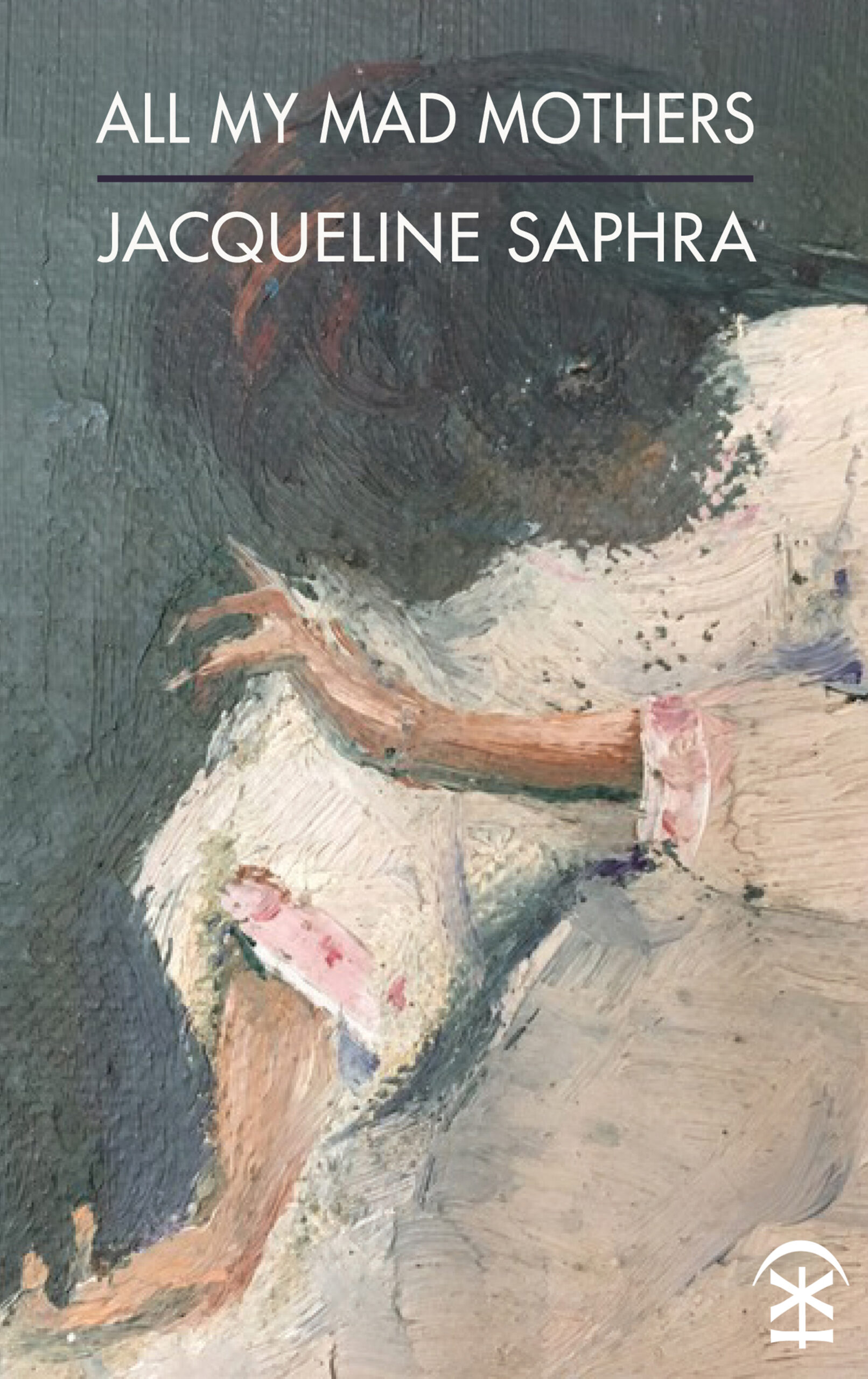

Jacqueline Saphra’s All My Mad Mothers is the work of an irresistible storyteller of the interstices between genders and generations, whether rendered raw by folly, or made joyous by frank acceptance of friendship and shared appetite. Ingeniously interweaving poetry and short prose poems, she keeps landing on the perfect detail, from how her daughter kills a chicken to the twist in a kiss. The most powerful word in the book, perhaps, is ‘let’s’.

‘Let’s wing it, old crow, deny the laws / of chance.’

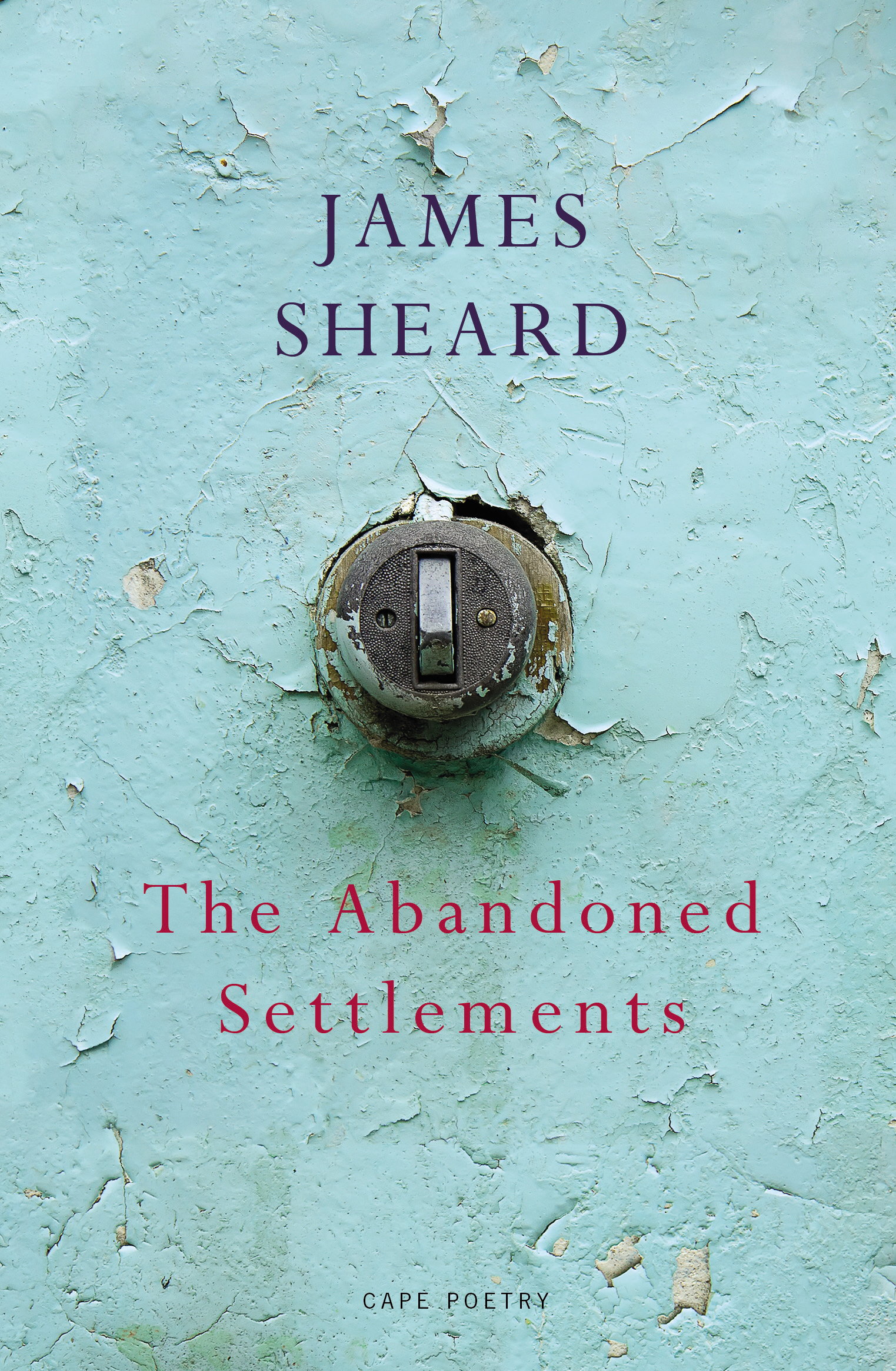

James Sheard’s The Abandoned Settlements attempts the paradoxical feat of locating our placelessness, our sense of constantly shifting between certainties of home or passion or sensibility, placing these moments of shift with extraordinary sure-footedness in the ongoing moment of the poem. His voice can encompass both devastating self-directed irony and unashamed emotional vulnerability in a single masterful gesture.

‘This it is, then / the bone music’

Michael Symmons Roberts’ Mancunia is also about the locution of location: the impressive architecture of the book imitates the mapping of a city which is almost Manchester, almost Utopia, representing its social and historic diversity in poems which describe with marvellous economy the subtle manner in which we allow a city’s soul to shape our own. It is a book about the possibility of belonging, not just as an individual, but as a citizen.

‘so what keeps this city alive is you.’

Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky with Exit Wounds displays a consistently astonishing command of phrase- and image-making in recounting the aftermath of war and migration involving three generations. It depicts a tense, terrifying, tender coming of age and coming to terms with deeply complex matters of traumatised abuse, and the difficult redemption of sexuality. It is a compellingly assured debut, the definitive arrival of a significant voice.

‘The most beautiful part / of your body is wherever / your mother’s shadow falls.’

The winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize for 2017, in the 25th anniversary year of the Prize, is Ocean Vuong.

This speech was given at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2017 Award Ceremony at the Wallace Collection, London, on 15 January 2018.

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘Judging the Eliot is a strange, strangely delightful duty. You are required to go beyond your taste, and yet not to lose touch with it; to read in good faith, while acknowledging your obvious limitations; and, finally, to commit to an agreement by committee about that at which most individuals would baulk: that a single book of poems can be ‘the best’. You get to disappoint scores of poets, in order to celebrate, not a few, not even that one book, but the art itself.’ – W. N. Herbert, Chair

T. S. Eliot Prize 2017: the Chair of judges’ speech by W. N. Herbert

Judging the Eliot is a strange, strangely delightful duty. You are required to go beyond your taste, and yet not to lose touch with it; to read in good faith, while acknowledging your obvious limitations; and, finally, to commit to an agreement by committee about that at which most individuals would baulk: that a single book of poems can be ‘the best’. You get to disappoint scores of poets, in order to celebrate, not a few, not even that one book, but the art itself.

Most importantly, you get, for a few dizzying moments, the delight of holding a whole year of poetry in your head. And what a year – over 150 collections! Our longlists were packed with strong contenders, and even our individual shortlists were more various than the number ten could handle – 25 would’ve been more like it. In short, it was not a lean year, and in the ten we selected we found richness and variety of voice, theme, and form, sustained, not just through a brilliant handful of poems or a galvanising sequence, but, marvellously, across entire collections.

Here is a brief alphabetic summation.

Tara Bergin’s The Tragic Death of Eleanor Marx explores the relationship between dominant narratives and those who attempt to interpret or embody them, moving from its titular suicide through translations of Flaubert, stage directions in Strindberg, jargon in academia, and the grim logic of fairy tales. Hers is an original voice of great power that flicks between speech and song, and between the borrowed and the wholly owned, with consummate ease.

‘I want a different kind of pain. / If I can get it once / I won’t come back again.’

Caroline Bird’s In These Days of Prohibition is equally pleasurable and disturbing, because it understands the genuinely strange ground on which we must build our thoughts and our emotions. In work of great and frequently comic poise it captures moments of absolute loss of control, and absolute freedom. We recognise that sustained unsettling comic virtuosity is the startling agent by which we engage with such loss, such freedom.

‘In the ambulance I turned to you and said, // “Don’t worry baby, I’ve got this.”’

Douglas Dunn’s The Noise of a Fly marks a triumphant return after sixteen years. It is rare to read work reflecting on ageing with such wit and formal mastery, riffing on major themes from throughout his career and resting on the possible secular communion with place, namely Fife, as a sort of poetic terroir. This is, as Dunn hints in his poem on two self-portraits by Rembrandt, the rich late period of an old master: wry, sensuous, utterly unsentimental.

‘Whatever I do is a robin’s prayer.’

Leontia Flynn’s The Radio sees one of Northern Ireland’s most assured voices continue her engagement with the alchemy of form in an effortlessly contemporary manner, indeed driving the thought thrillingly through longer stanza forms, including a brilliant elegy for Heaney. The exposure of family, and its intimate matrix of the generations, to the equal threats of history and human frailty is played out in work with an intense sense of place and moment.

‘the faint persistent hum of the first Real Thing.’

Roddy Lumsden’s So Glad I’m Me is fully fluent in its own unique English, in which the everyday and the elegiac and the elliptical are mashed together into a rich music. Thanks to this command of phrase, his intense savouring of the minutiae of relationship, food, and song achieves a delirious democracy of the senses and the intellect. This is poetry which manages to survive in those fragmentary glimpses of our lives and our other, potential lives, and realises –

‘Everything has something to do with love.’

Robert Minhinnick’s Diary of the Last Man casts a ferocious eye on the natural world’s vulnerabilities – and our own – in the dysfunctional relationship we have created with that world. His is an apocalyptic vision which moves from isolated contemplation of the fragile beauties of place, most usually South Wales, through atrocity in Iraq, to a community of translations from the Turkish, Arabic and Welsh, achieving a bleakly affirming global regard.

‘Yes this is what happens / when the old men make us wait’

Jacqueline Saphra’s All My Mad Mothers is the work of an irresistible storyteller of the interstices between genders and generations, whether rendered raw by folly, or made joyous by frank acceptance of friendship and shared appetite. Ingeniously interweaving poetry and short prose poems, she keeps landing on the perfect detail, from how her daughter kills a chicken to the twist in a kiss. The most powerful word in the book, perhaps, is ‘let’s’.

‘Let’s wing it, old crow, deny the laws / of chance.’

James Sheard’s The Abandoned Settlements attempts the paradoxical feat of locating our placelessness, our sense of constantly shifting between certainties of home or passion or sensibility, placing these moments of shift with extraordinary sure-footedness in the ongoing moment of the poem. His voice can encompass both devastating self-directed irony and unashamed emotional vulnerability in a single masterful gesture.

‘This it is, then / the bone music’

Michael Symmons Roberts’ Mancunia is also about the locution of location: the impressive architecture of the book imitates the mapping of a city which is almost Manchester, almost Utopia, representing its social and historic diversity in poems which describe with marvellous economy the subtle manner in which we allow a city’s soul to shape our own. It is a book about the possibility of belonging, not just as an individual, but as a citizen.

‘so what keeps this city alive is you.’

Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky with Exit Wounds displays a consistently astonishing command of phrase- and image-making in recounting the aftermath of war and migration involving three generations. It depicts a tense, terrifying, tender coming of age and coming to terms with deeply complex matters of traumatised abuse, and the difficult redemption of sexuality. It is a compellingly assured debut, the definitive arrival of a significant voice.

‘The most beautiful part / of your body is wherever / your mother’s shadow falls.’

The winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize for 2017, in the 25th anniversary year of the Prize, is Ocean Vuong.

This speech was given at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2017 Award Ceremony at the Wallace Collection, London, on 15 January 2018.