2000

T. S. Eliot Prize

Winner

The Chair of the judges’ speech

Announcements

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

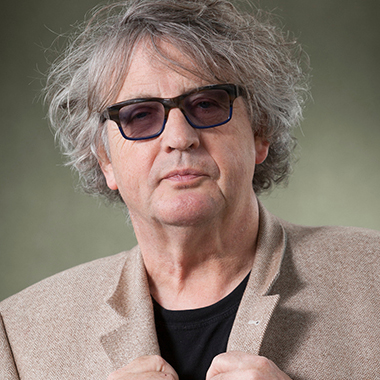

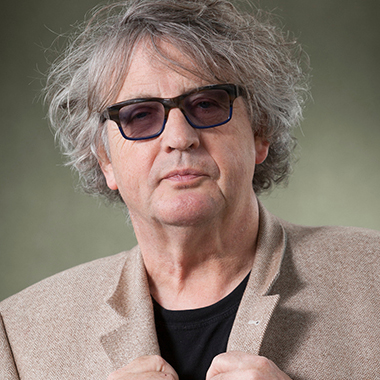

‘It’s my great pleasure, on behalf of my fellow judges Kathleen Jamie and Glyn Maxwell, to announce the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize. Before I do so, I’d like to remind you of the vigour and variety of the books on the shortlist, a shortlist which, given the terrific resonance and range of poetry published last year, we found difficult enough to make.’ – Paul Muldoon, Chair

T. S. Eliot Prize 2020: the Chair of judges’ speech, by Paul Muldoon

It’s my great pleasure, on behalf of my fellow judges Kathleen Jamie and Glyn Maxwell, to announce the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize. Before I do so, I’d like to remind you of the vigour and variety of the books on the shortlist, a shortlist which, given the terrific resonance and range of poetry published last year, we found difficult enough to make.

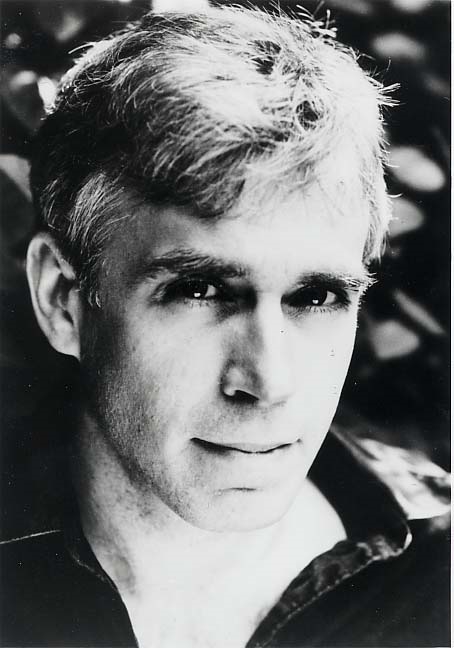

First comes John Burnside’s The Asylum Dance, a collection notable for its inventories of longing and loss: ‘forgive me’, John Burnside writes in the last lines of the last poem in his book, ‘for not being the man I seem / not lost or found / but somewhere in between’.

In Men in the Off Hours, Anne Carson brings a witty and wide-ranging intelligence to bear on subjects as diverse as Thucydides and ‘TV Men’: ‘TV makes things disappear. Oddly the word comes from Latin videre ‘to see’.’

Michael Donaghy’s Conjure summons up poignant and pithy poems on the tried but true subjects of permanence and mutability including, in the case of ‘Needlework’, a poem meant to be read as a tattoo: ‘The serpent sheds her skin and yet / The pattern she’d as soon forget / Recalls itself. By this I swear / I am the sentence that I bare’.

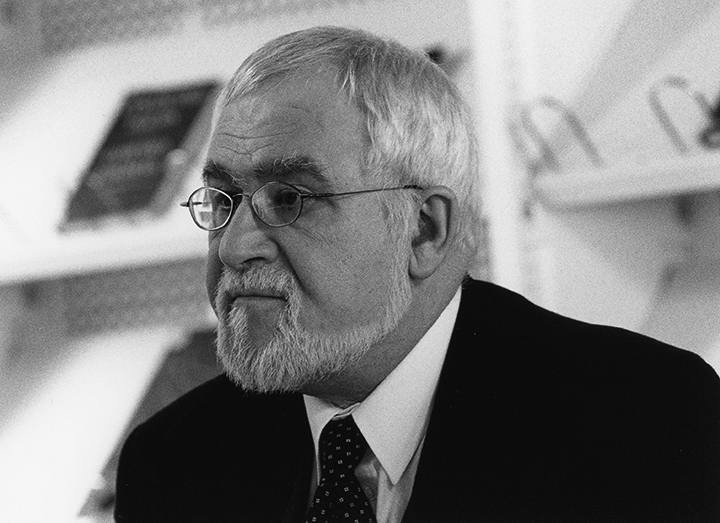

In many of the poems in The Year’s Afternoon, Douglas Dunn movingly bares, and bears, the burdens, along with the occasional blessings, of advancing years: ‘My empty shoes at the bedside will say to me, / ‘When are we taking you back? Why be patient? / You have much more, so much more, to lose’.’

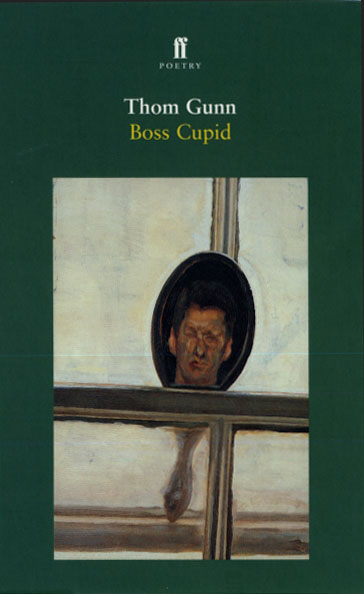

In ‘Blues for the New Year’, a poem representative of those collected in Boss Cupid, Thom Gunn also seems to be just ever so slightly reconciled to growing a little older: ‘I’m sixty-seven, / and have high blood pressure, / and probably shouldn’t / be doing speed at all.’

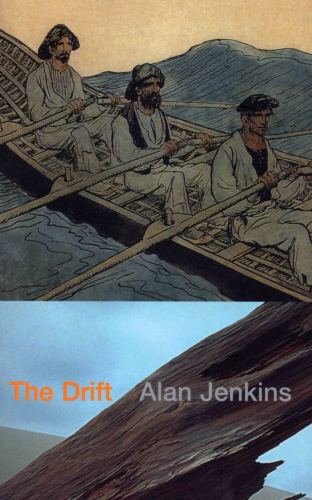

The speakers of many of the poems in Alan Jenkins’s The Drift are engaged with what W. B. Yeats described as the only two fit subjects – sex and the dead – and exhibit a finely tuned combination of resolution and self-reproach, as in ‘House-Clearing’: ‘though she blah’d and blathered / with the neighbours endlessly about my books, / has she opened those since – when? Since she was moved to tears / by how unhappy all my poems made me sound?’

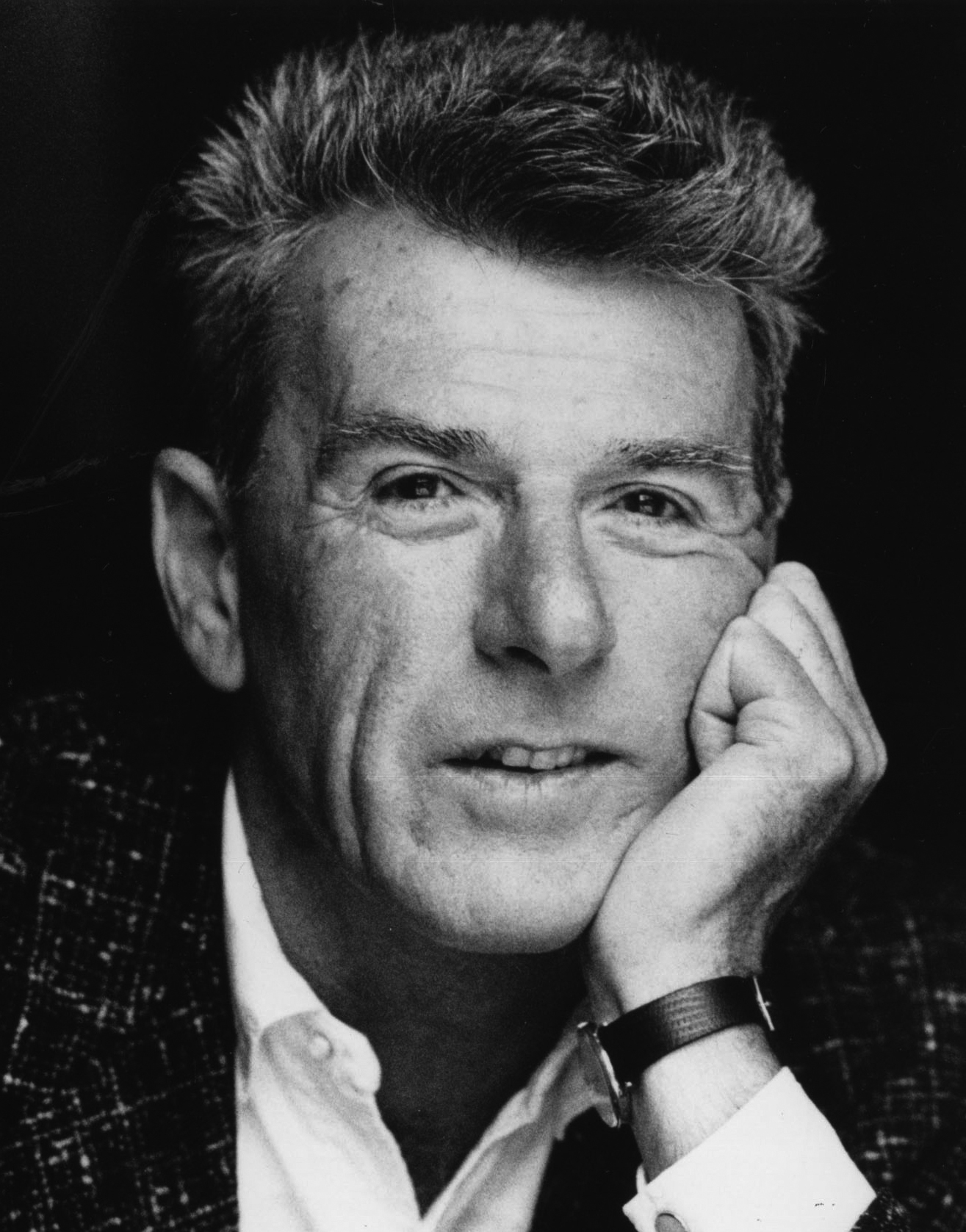

With The Weather in Japan, Michael Longley gives us poems at once delicate and depth-charged: ‘It was against the law for Jews to buy asparagus. / Only Aryan piss was allowed that whiff of compost. / I bring you a bunch held together with elastic bands. / Let us prepare melted butter, shavings of parmesan, / And make a meal out of the mouthwatering fasces.’

Roddy Lumsden’s The Book of Love couples great linguistic high jinks with a good old-fashioned sense of humour: ‘Such things occur: I am driving back to Dunbar / when Shelley strips naked in the passenger seat / to show me the Celtic serpent tattoo / which twists all over the pale force of her body, / the forked tongue flicking the down of her belly. / You must put your faith in something, she says.’

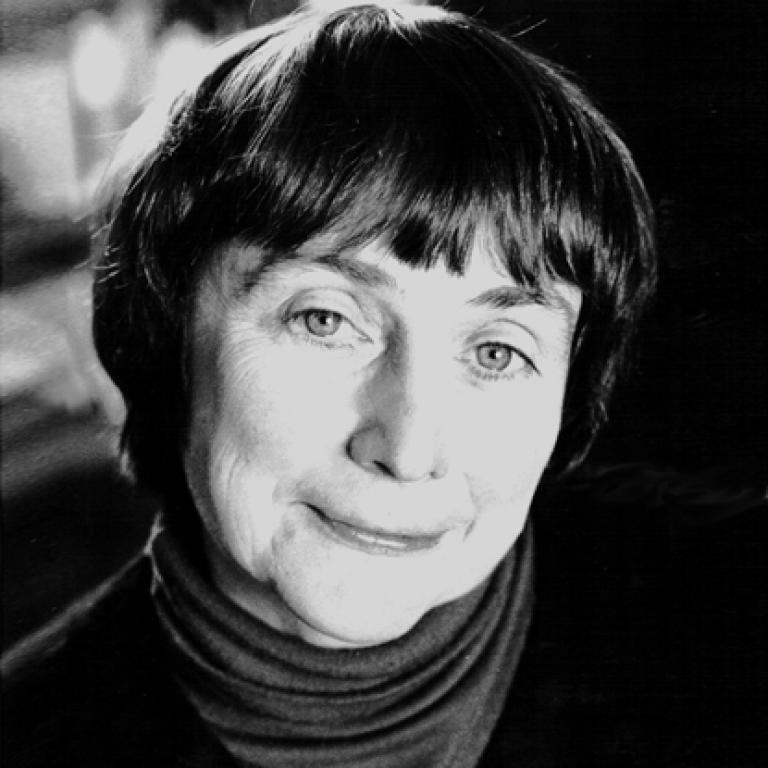

What Anne Stevenson puts her faith in, here in Granny Scarecrow as in her previous collections, is closely observed detail followed by closely observed detail, often shot through with a great sense of absence: ‘Habits the hands have, reaching for this and that, / (tea kettle, orange squeezer, milk jug, / frying pan, sugar jar, coffee mug) / manipulate, or make, a habitat / become a genii loci, working on / quietly in the house when you’ve gone.’

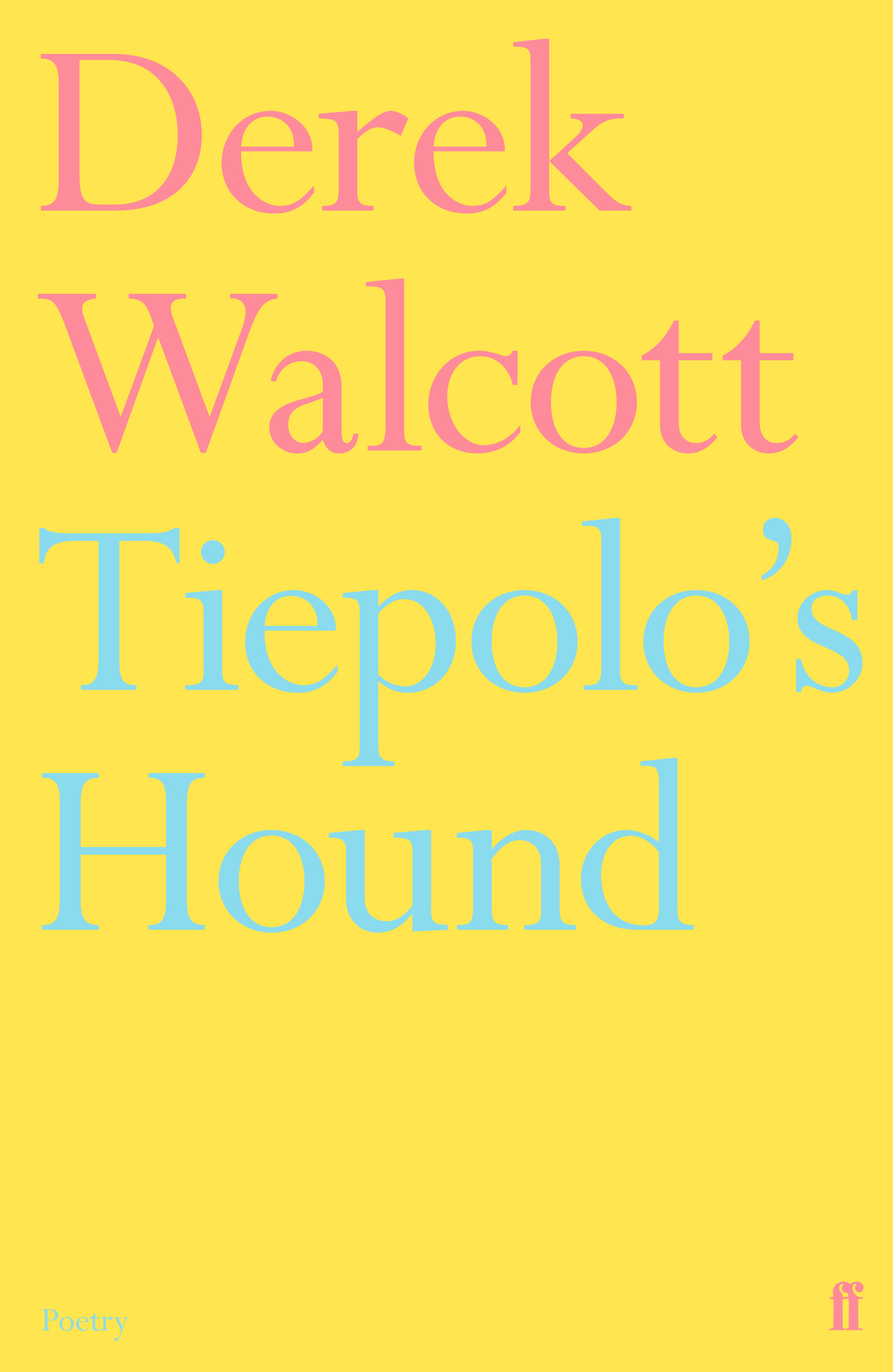

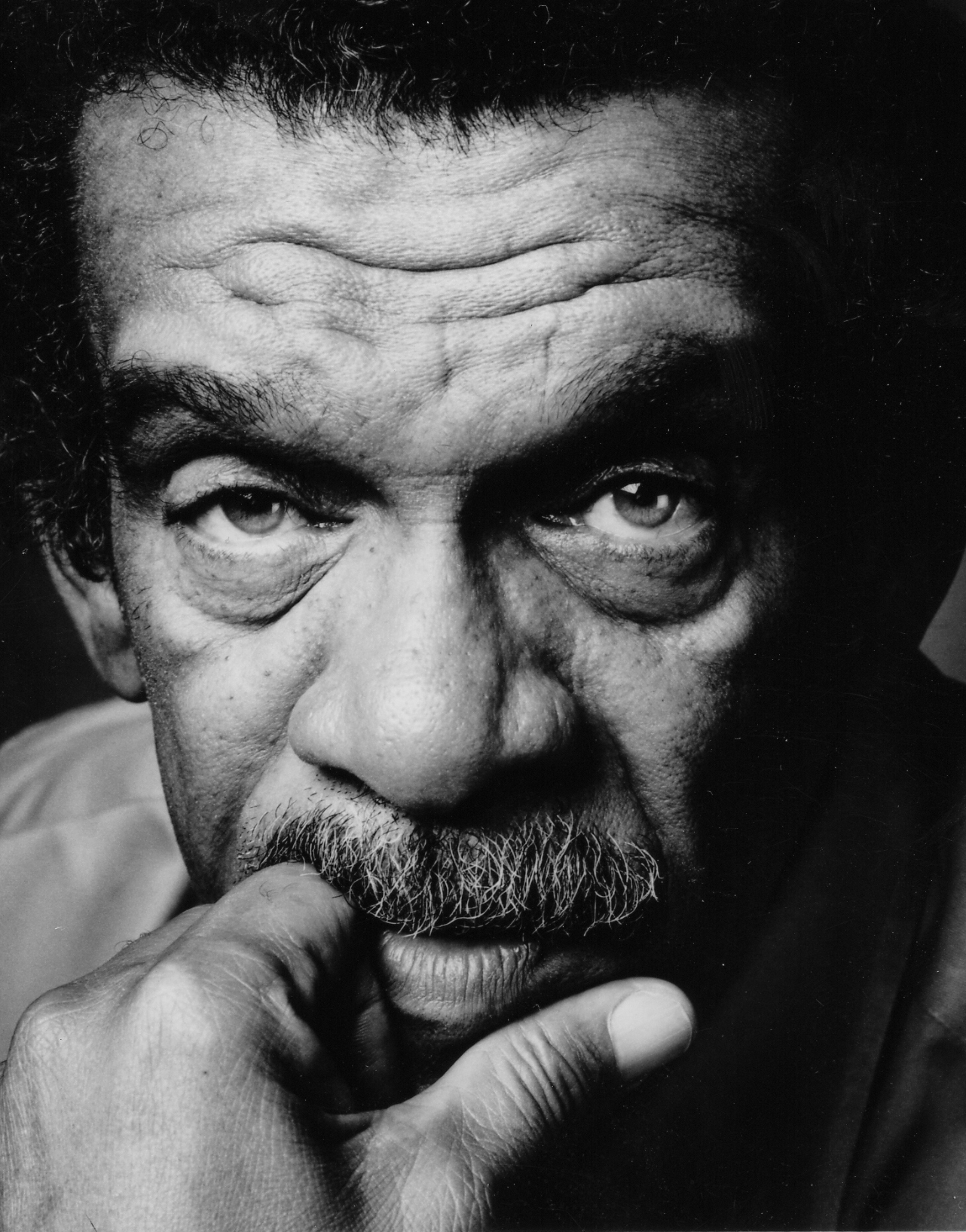

That preoccupation with some missing detail is also at the heart of Derek Walcott’s Tiepolo’s Hound – that detail being ‘a slash of pink’, remembered or imagined, ‘on the inner thigh / of a white hound’ which prompts this wonderfully lush and leisurely long poem.

And the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize for the best book of poems published in the United Kingdom and Ireland in the year 2000 is Michael Longley’s The Weather in Japan.

This speech was given at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2000 award ceremony at Lancaster House, London, on 22 January 2001.

The Chair of the Judges’ speech

‘It’s my great pleasure, on behalf of my fellow judges Kathleen Jamie and Glyn Maxwell, to announce the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize. Before I do so, I’d like to remind you of the vigour and variety of the books on the shortlist, a shortlist which, given the terrific resonance and range of poetry published last year, we found difficult enough to make.’ – Paul Muldoon, Chair

T. S. Eliot Prize 2020: the Chair of judges’ speech, by Paul Muldoon

It’s my great pleasure, on behalf of my fellow judges Kathleen Jamie and Glyn Maxwell, to announce the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize. Before I do so, I’d like to remind you of the vigour and variety of the books on the shortlist, a shortlist which, given the terrific resonance and range of poetry published last year, we found difficult enough to make.

First comes John Burnside’s The Asylum Dance, a collection notable for its inventories of longing and loss: ‘forgive me’, John Burnside writes in the last lines of the last poem in his book, ‘for not being the man I seem / not lost or found / but somewhere in between’.

In Men in the Off Hours, Anne Carson brings a witty and wide-ranging intelligence to bear on subjects as diverse as Thucydides and ‘TV Men’: ‘TV makes things disappear. Oddly the word comes from Latin videre ‘to see’.’

Michael Donaghy’s Conjure summons up poignant and pithy poems on the tried but true subjects of permanence and mutability including, in the case of ‘Needlework’, a poem meant to be read as a tattoo: ‘The serpent sheds her skin and yet / The pattern she’d as soon forget / Recalls itself. By this I swear / I am the sentence that I bare’.

In many of the poems in The Year’s Afternoon, Douglas Dunn movingly bares, and bears, the burdens, along with the occasional blessings, of advancing years: ‘My empty shoes at the bedside will say to me, / ‘When are we taking you back? Why be patient? / You have much more, so much more, to lose’.’

In ‘Blues for the New Year’, a poem representative of those collected in Boss Cupid, Thom Gunn also seems to be just ever so slightly reconciled to growing a little older: ‘I’m sixty-seven, / and have high blood pressure, / and probably shouldn’t / be doing speed at all.’

The speakers of many of the poems in Alan Jenkins’s The Drift are engaged with what W. B. Yeats described as the only two fit subjects – sex and the dead – and exhibit a finely tuned combination of resolution and self-reproach, as in ‘House-Clearing’: ‘though she blah’d and blathered / with the neighbours endlessly about my books, / has she opened those since – when? Since she was moved to tears / by how unhappy all my poems made me sound?’

With The Weather in Japan, Michael Longley gives us poems at once delicate and depth-charged: ‘It was against the law for Jews to buy asparagus. / Only Aryan piss was allowed that whiff of compost. / I bring you a bunch held together with elastic bands. / Let us prepare melted butter, shavings of parmesan, / And make a meal out of the mouthwatering fasces.’

Roddy Lumsden’s The Book of Love couples great linguistic high jinks with a good old-fashioned sense of humour: ‘Such things occur: I am driving back to Dunbar / when Shelley strips naked in the passenger seat / to show me the Celtic serpent tattoo / which twists all over the pale force of her body, / the forked tongue flicking the down of her belly. / You must put your faith in something, she says.’

What Anne Stevenson puts her faith in, here in Granny Scarecrow as in her previous collections, is closely observed detail followed by closely observed detail, often shot through with a great sense of absence: ‘Habits the hands have, reaching for this and that, / (tea kettle, orange squeezer, milk jug, / frying pan, sugar jar, coffee mug) / manipulate, or make, a habitat / become a genii loci, working on / quietly in the house when you’ve gone.’

That preoccupation with some missing detail is also at the heart of Derek Walcott’s Tiepolo’s Hound – that detail being ‘a slash of pink’, remembered or imagined, ‘on the inner thigh / of a white hound’ which prompts this wonderfully lush and leisurely long poem.

And the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize for the best book of poems published in the United Kingdom and Ireland in the year 2000 is Michael Longley’s The Weather in Japan.

This speech was given at the T. S. Eliot Prize 2000 award ceremony at Lancaster House, London, on 22 January 2001.