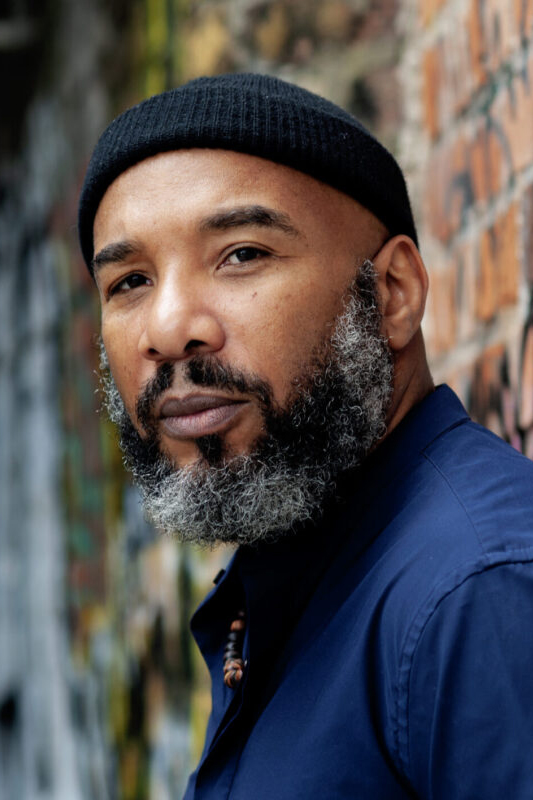

Anthony Joseph was born in Trinidad. He is a poet, novelist, academic and musician. He holds a PhD in Creative Writing from Goldsmiths University and is a Lecturer in Creative Writing at King’s College London. He was the Colm Tóibín Fellow in Creative Writing at the University of Liverpool in 2018 and was awarded a Jerwood Compton Poetry Fellowship 2019/20....

Review

Interview

Review

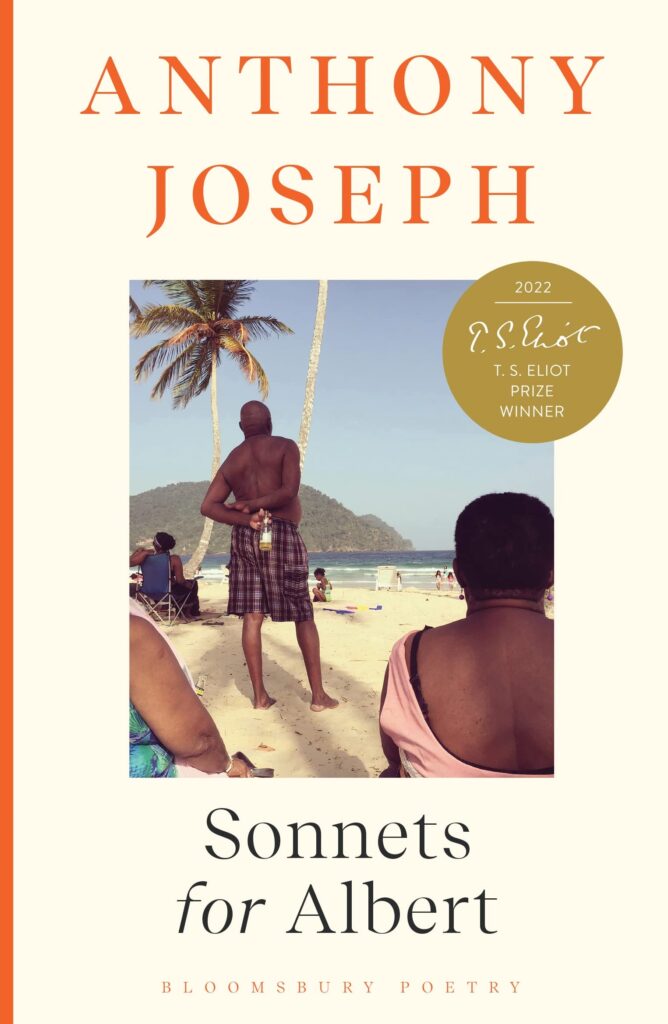

Anthony Joseph’s Sonnets for Albert explores how we cling to precious moments in time and, when necessary, construct absent loved ones from scant coordinates, writes John Field

Interview

Anthony Joseph’s Sonnets for Albert (Bloomsbury Poetry, 2022), shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2022, explores the difficulties of truth-telling and how this can be overcome by love. We spoke to Anthony Joseph about his collection

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

The Complete T. S. Eliot Prize 2022 Shortlist Readings

Anthony Joseph reads from Sonnets for Albert at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Oliver Fox reads from Anthony Joseph’s Sonnets for Albert

Anthony Joseph reads ‘P.O.S.G.H. 1’

Anthony Joseph talks about his work

Anthony Joseph reads ‘El Socorro’

Anthony Joseph reads ‘Jogie Road’

Related News Stories

In 2023 the T. S. Eliot Prize celebrated its 30th anniversary. We marked the occasion by looking back at the collections which have won ‘the Prize poets most want to win’ (Sir Andrew Motion). In announcing Anthony Joseph’s Sonnets for Albert (Bloomsbury Poetry) as the winner of the T. S....

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2022 is Anthony Joseph for his collection Sonnets for Albert published by Bloomsbury Poetry.

Judges Jean Sprackland (Chair), Hannah Lowe and Roger Robinson have chosen the 2022 T. S. Eliot Prize shortlist from a record 201 poetry collections submitted by British and Irish publishers. The eclectic list comprises seasoned poets, including one previous winner, and five debut collections. Victoria Adukwei Bulley – Quiet (Faber &...