Paul Farley was born in Liverpool and studied at the Chelsea School of Art. He has published six collections of poetry with Picador, including: The Boy from the Chemist is Here to See You (1998), which won the Forward Prize for Best First Collection; The Ice Age (2002), which won the Whitbread Poetry Award; and The Mizzy (2019), which was...

Review

Review

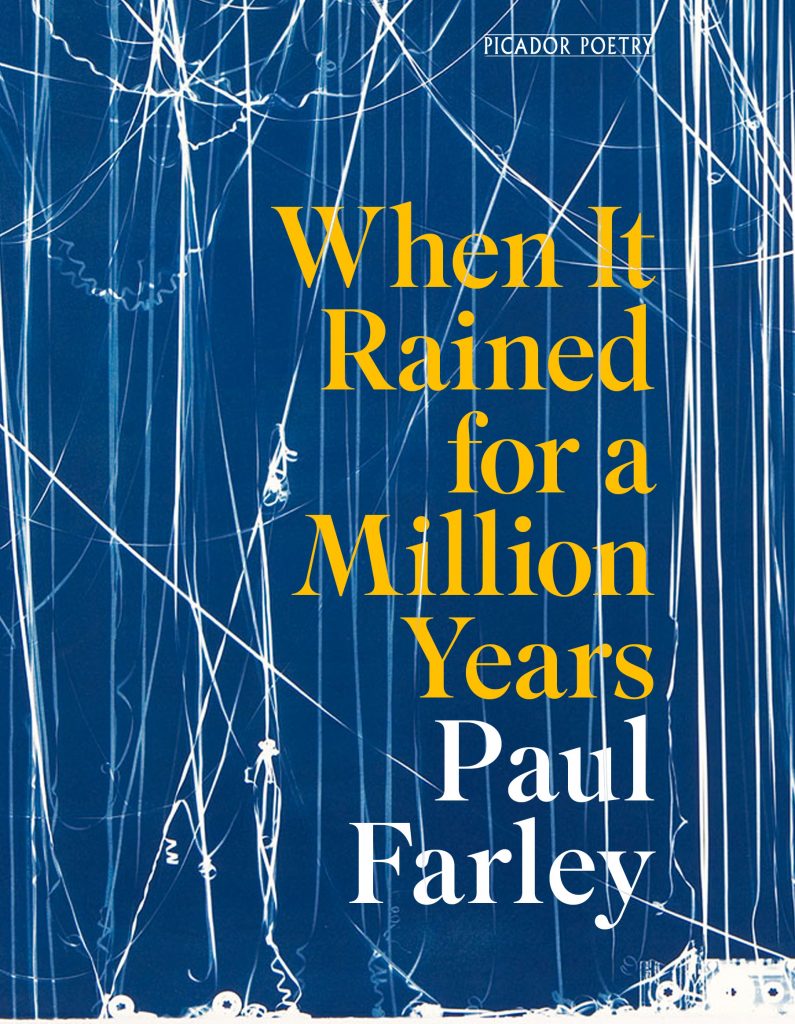

Celebrating and rewarding the act of reading, When It Rained for a Million Years is an opportunity to view the world through Paul Farley’s distorting lenses

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

Paul Farley talks about his work

Paul Farley reads his poem ‘A Rewilding’

Paul Farley reads his poem ‘The Gorilla’

Paul Farley reads ‘Three Rings’

Related News Stories

Paul Farley, shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2025 with his collection When It Rained for a Million Years (Picador Poetry), is the featured poet in this week’s Eliot Prize newsletter. The newsletter tells you about the wide range of content we have just published to help you get...

We’re delighted to announce the T. S. Eliot Prize 2025 Shortlist, which offers ‘something for everyone’ in collections of ‘great range, suggestiveness and power’. Judges Michael Hofmann (Chair), Patience Agbabi and Niall Campbell chose the Shortlist from 177 poetry collections submitted by 64 British and Irish publishers. The diverse list...

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce the judges for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2025. Chair Michael Hofmann will be joined on the panel by Patience Agbabi and Niall Campbell. Michael Hofmann said: I’m delighted to be asked to judge the T. S. Eliot Prize and look...