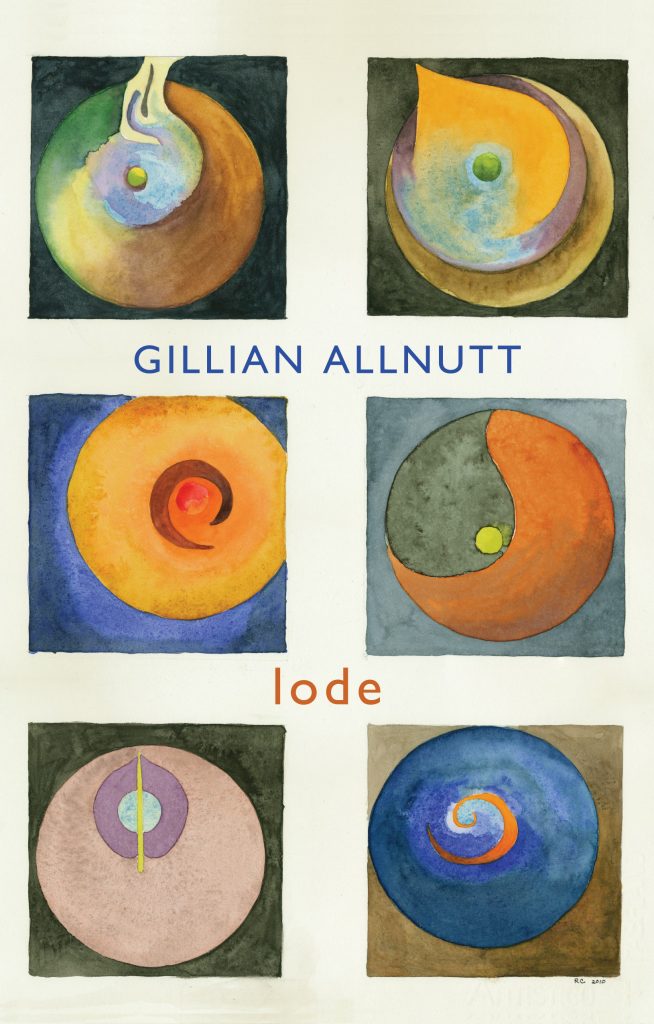

Gillian Allnutt was born in London but spent half her childhood in Newcastle upon Tyne. Nantucket and the Angel (1997) and Lintel (2001) were shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize and poems from these collections are included in her Bloodaxe retrospective How the Bicycle Shone: New & Selected Poems (2007), a Poetry Book Society Special Commendation. Lode (Bloodaxe Books)...

Review

Review

In Lode Gillian Allnutt explores constraint and freedom, protection and danger and brings the full force of history to bear upon the words she weighs so carefully, writes John Field

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

Gillian Allnutt talks about her work

Gillian Allnutt reads ‘At 71’

Gillian Allnutt reads ‘Solitude’

Gillian Allnutt reads ‘Poem for John Clinging’

Related News Stories

Gillian Allnutt, shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2025 with her collection Lode (Bloodaxe Books), is the featured poet in this week’s Eliot Prize newsletter. The newsletter tells you about the wide range of content we have just published to help you get to know Gillian and her work....

We’re delighted to announce the T. S. Eliot Prize 2025 Shortlist, which offers ‘something for everyone’ in collections of ‘great range, suggestiveness and power’. Judges Michael Hofmann (Chair), Patience Agbabi and Niall Campbell chose the Shortlist from 177 poetry collections submitted by 64 British and Irish publishers. The diverse list...

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce the judges for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2025. Chair Michael Hofmann will be joined on the panel by Patience Agbabi and Niall Campbell. Michael Hofmann said: I’m delighted to be asked to judge the T. S. Eliot Prize and look...