Rachel Mann is a priest, writer and broadcaster. She is the author of thirteen books, including her debut poetry collection, A Kingdom of Love (Carcanet Press, 2019), and the acclaimed non-fiction, Fierce Imaginings: The Great War, Ritual, Memory and God (Darton, Longman & Todd, 2017). She is a Visiting Teaching Fellow at The Manchester Writing School, and broadcasts regularly, including...

Review

Review

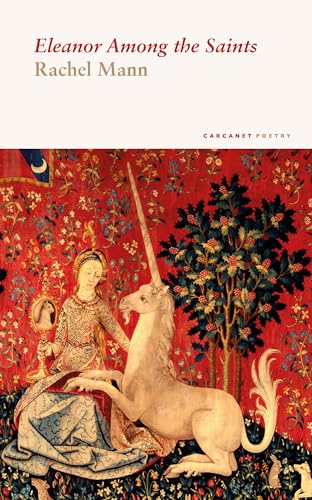

In Rachel Mann’s Eleanor Among the Saints, language is underpinned by trans history and the liturgy. It’s a collection of struggle, but also of consolation, writes John Field

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

Rachel Mann reads from Eleanor Among the Saints at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Young Critic Tallulah Howarth reviews Rachel Mann’s Eleanor Among the Saints

Rachel Mann talks about her work

Rachel Mann reads ‘Eleanor as a Sixteen Year Old Murdered Trans Girl, What is Known’

Rachel Mann reads ‘Eleanor as Julian as Margery’

Rachel Mann reads ‘Embroidering a Priest’

Related News Stories

There was a brilliant response to the T. S. Eliot Prize 2024 Shortlist Readings, held at the Royal Festival Hall, London, on 12 January 2025. Each of the ten shortlisted poets, including Karen McCarthy Woolf (shown above) gave extraordinary readings at what is the largest annual poetry event in the...

The T.S. Eliot Prize and The Poetry Society are excited to share the second set of video reviews created as part of the Young Critics Scheme. ‘Their inventiveness and attention to poetic detail is always such a delight’, writes Cia Mangat of The Poetry Society, on the Children’s Poetry Summit...

I hope that [Eleanor Among the Saints] will enable anyone to discover, no matter what they think about gender or sexuality, to discover at the edge of words, the edge of what’s sayable, the edge of what poetry can do, that there’s a sense of openness and promise, and new...

We are thrilled to announce the T. S. Eliot Prize 2024 Shortlist, chosen by judges Mimi Khalvati (Chair), Anthony Joseph and Hannah Sullivan from 187 poetry collections submitted by British and Irish publishers. The eclectic list comprises seasoned poets, two debuts, two second collections, and two previously shortlisted poets from...