Yomi Ṣode is an award-winning Nigerian British writer and lives in London. He was a 2019/20 Jerwood Compton Poetry Fellow and was shortlisted for the Brunel International African Poetry Prize 2021. His acclaimed one-man show COAT toured nationally to sold-out audiences, including at the Brighton Festival, Roundhouse Camden and Battersea Arts Centre. In 2020 his libretto Remnants, written in collaboration...

Review

Interview

Review

Yomi Ṣode’s Manorism is an urgent interrogation of double standards and lays bare the doublethink Black men and boys are required to negotiate, writes John Field

Interview

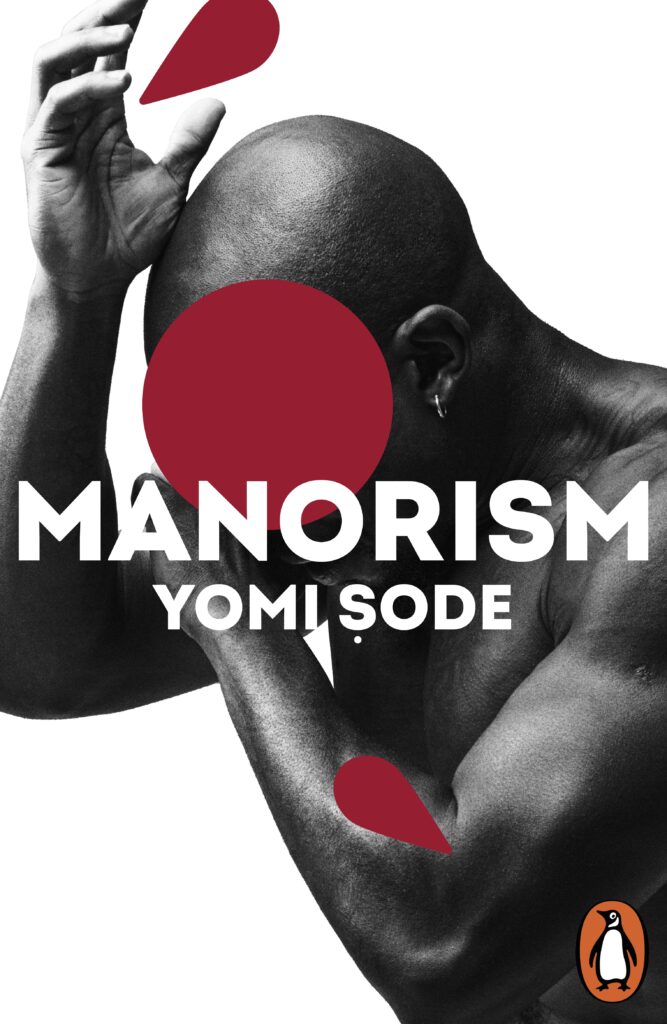

Yomi Ṣode is shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize 2022 for his debut collection, Manorism (Penguin Poetry, 2022). We asked him about its themes of identity, violence, masculinity, resistance and rest

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

Yomi Ṣode reads from Manorism at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Yomi Ṣode talks about his work

Yomi Ṣode reads ‘Fugitives’

Yomi Ṣode reads ‘Distant Daily Ijó’

Yomi Ṣode reads ‘[Insert Name]’s Mother: A Ghazal’

Related News Stories

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2022 is Anthony Joseph for his collection Sonnets for Albert published by Bloomsbury Poetry.

Judges Jean Sprackland (Chair), Hannah Lowe and Roger Robinson have chosen the 2022 T. S. Eliot Prize shortlist from a record 201 poetry collections submitted by British and Irish publishers. The eclectic list comprises seasoned poets, including one previous winner, and five debut collections. Victoria Adukwei Bulley – Quiet (Faber &...