Raymond Antrobus was born in Hackney, London, to an English mother and Jamaican father. His collections include two T. S. Eliot Prize shortlisted titles, Signs, Music (Picador Poetry, 2024) and All The Names Given (Picador Poetry, 2021); The Perseverance (Penned in the Margins / Tin House, 2018), which won the Ted Hughes Award, Rathbones Folio Prize and Somerset Maugham Award; and...

Review

Review

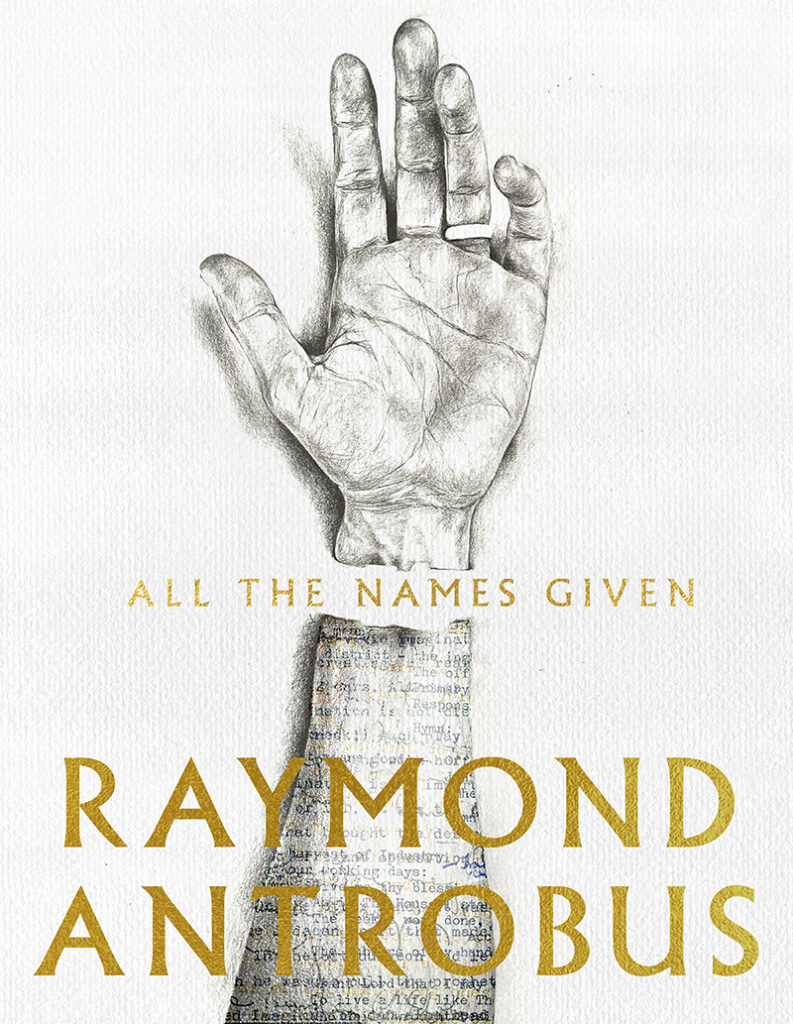

Raymond Antrobus's All the Names Given explores both the gaps between sound and silence, and the uneasy relationship between those who have been silenced and those who have silenced them, writes John Field

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

Raymond Antrobus reads from All the Names Given at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Raymond Antrobus reads ‘For Tyrone Givans’

Raymond Antrobus reads ‘Language Signs’

Raymond Antrobus reads ‘Sutton Road Cemetery’

Raymond Antrobus talks about his work

Raymond Antrobus reads ‘Plantation Paint’

Related News Stories

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2021 is Joelle Taylor for C+nto & Othered Poems, published by The Westbourne Press. Chair Glyn Maxwell said: Every book on the Shortlist had a strong claim on the award. We found...

Judges Glyn Maxwell (Chair), Caroline Bird and Zaffar Kunial have chosen the T. S. Eliot Prize 2021 Shortlist from a record 177 poetry collections submitted by British and Irish publishers. The Shortlist consists of an eclectic mixture of established poets, none of whom has previously won the Prize, and...

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce the judges for the 2021 Prize. The panel will be chaired by Glyn Maxwell, alongside Caroline Bird and Zaffar Kunial. The 2021 judging panel will be looking for the best new poetry collection written in English and published in 2021. The...