Glyn Maxwell was born in England to Welsh parents and now lives in London. He has won several awards for his many poetry collections, including the Somerset Maugham Prize, the E. M. Forster Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize. His work has been shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize (three...

Review

Review

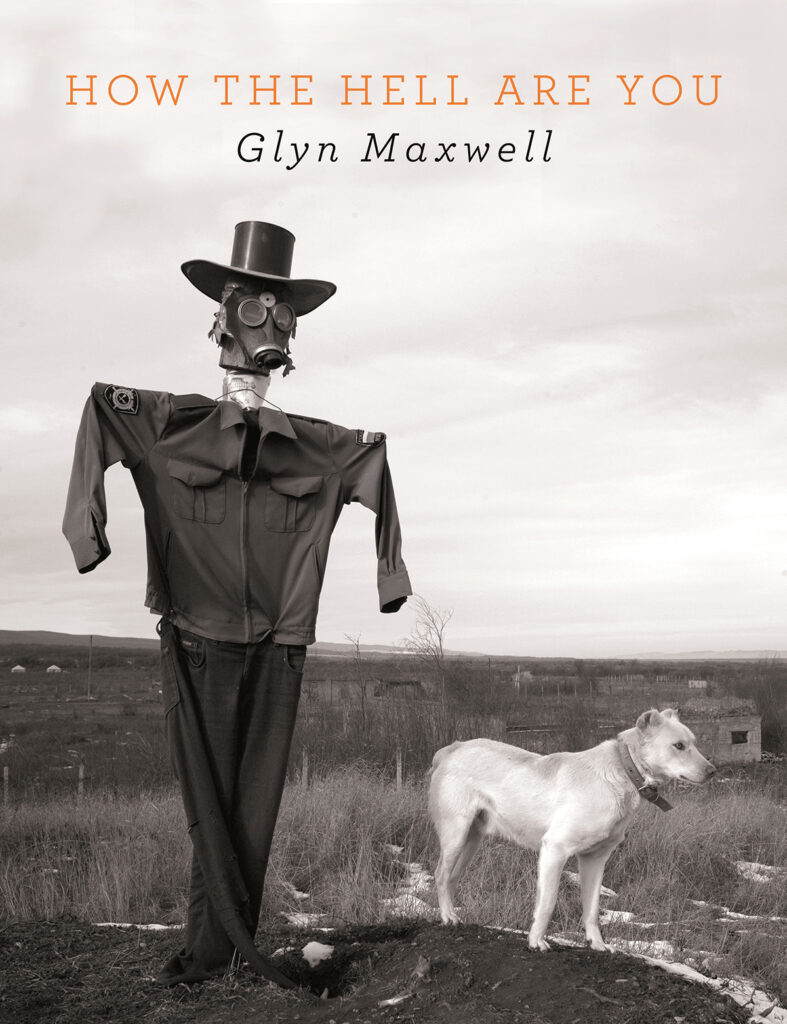

Glyn Maxwell's How the hell are you 'is rooted in pain and loss, in humanity’s insignificance. Yes, it’s brilliant on writing (and reading) but it’s warmly human too, with poems that are authentic and urgent', writes John Field

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

Glyn Maxwell reads ‘The Forecast’

Glyn Maxwell talks about his work

Glyn Maxwell reads ‘How the hell are you’

Related News Stories

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2020 is Bhanu Kapil for How to Wash a Heart, published by Pavilion Poetry (Liverpool University Press). Chair Lavinia Greenlaw said: Our Shortlist celebrated the ways in which poetry is responding to...

Judges Lavinia Greenlaw (Chair), Mona Arshi and Andrew McMillan have chosen the 2020 T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist from 153 poetry collections submitted by British and Irish publishers. The shortlist comprises work from five men and five women; two Americans; as well as poets of Native American, Chinese Indonesian and...

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce the judges for the 2020 Prize. The panel will be chaired by Lavinia Greenlaw, alongside Mona Arshi and Andrew McMillan. The 2020 judging panel will be looking for the best new poetry collection written in English and published in 2020. The...