Bhanu Kapil was born in England to Indian parents, and she grew up in a South Asian, working-class community in London. She lives in the UK and US where she spent 21 years at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado. She is the author of six books of poetry/prose: The Vertical Interrogation of Strangers (Kelsey Street Press, 2001), Incubation: a space...

Review

Review

The poetry in Bhanu Kapil’s How to Wash a Heart is courageous and honest. There is no convalescence for the immigrant heart and the domestic microaggressions it endures at its destination are just a different kind of war, writes John Field

Read the

Reader's Notes

Videos

T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings 2020

Aea Varfis-van Warmelo reads from Bhanu Kapil’s How to Wash a Heart

Bhanu reads an extract from How to Wash a Heart

Bhanu reads an extract from How to Wash a Heart

Bhanu Kapil talks about her work

Bhanu Kapil reads an extract from How to Wash a Heart

Bhanu Kapil reads an extract from How to Wash a Heart

Bhanu Kapil reads an extract from How to Wash a Heart

Related News Stories

In 2023 the T. S. Eliot Prize celebrated its 30th anniversary. We marked the occasion by looking back at the collections which have won ‘the Prize poets most want to win’ (Sir Andrew Motion). Bhanu Kapil won the T. S. Eliot Prize 2020, judged by Lavinia Greenlaw (Chair), Mona Arshi...

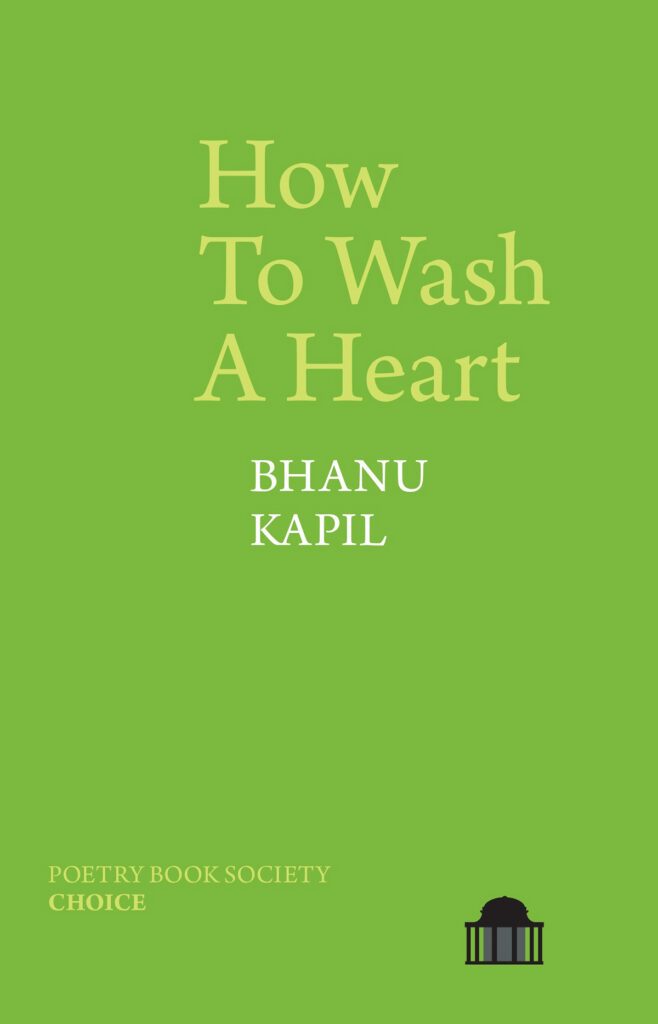

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2020 is Bhanu Kapil for How to Wash a Heart, published by Pavilion Poetry (Liverpool University Press). Chair Lavinia Greenlaw said: Our Shortlist celebrated the ways in which poetry is responding to...

‘The poets we have published so far each has a distinctive voice, but all share a desire to take a risk with form and ideas’, writes Deryn Rees-Jones 2021 will mark the seventh anniversary of Pavilion Poetry. Our list is small – we usually only publish three books each spring...

Judges Lavinia Greenlaw (Chair), Mona Arshi and Andrew McMillan have chosen the 2020 T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist from 153 poetry collections submitted by British and Irish publishers. The shortlist comprises work from five men and five women; two Americans; as well as poets of Native American, Chinese Indonesian and...

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce the judges for the 2020 Prize. The panel will be chaired by Lavinia Greenlaw, alongside Mona Arshi and Andrew McMillan. The 2020 judging panel will be looking for the best new poetry collection written in English and published in 2020. The...