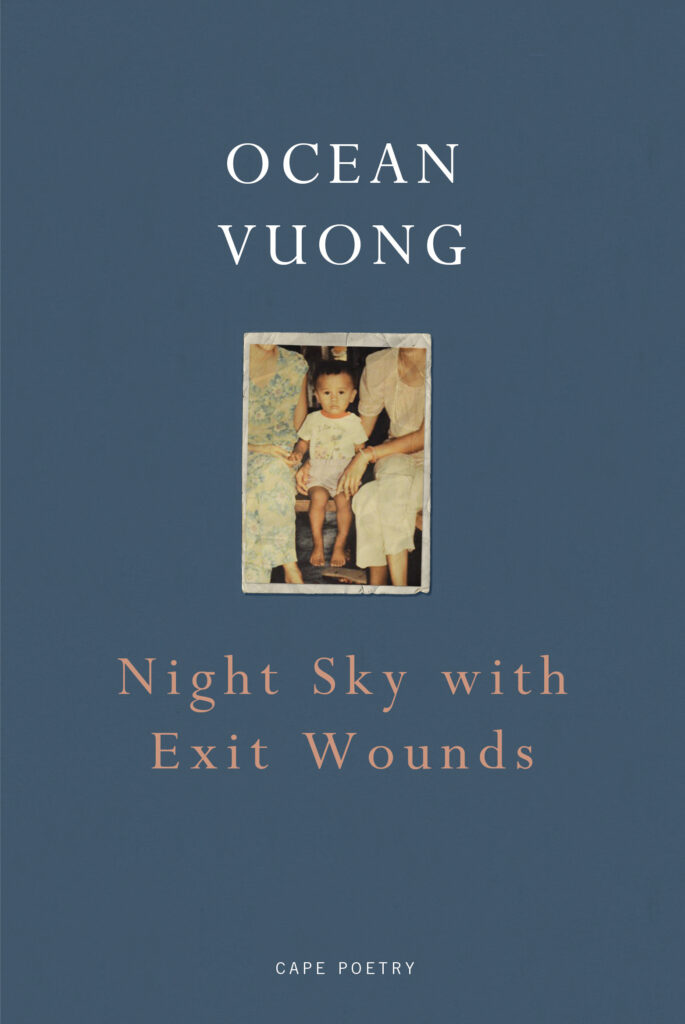

Born in Saigon, Vietnam, Ocean Vuong is the author of the best-selling debut, Night Sky with Exit Wounds (Cape Poetry), awarded the T. S. Eliot Prize 2017 and also the winner of the Whiting Award, the Thom Gunn Award, and the Forward Prize for Best First Collection. Since being awarded the Eliot Prize, Ocean Vuong has published the New York...

Review

Review

'Ocean Vuong's Night Sky with Exit Wounds meditates on violence. The Vietnam War’s legacy of trauma is considered through these searing, painful, playful, beautiful poems', writes John Field

Videos

Ocean Vuong reads from Night Sky with Exit Wounds at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Tracey Hammett reads from Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky With Exit Wounds

Ocean Vuong reads ‘A Little Closer’

Ocean Vuong reads ‘Telemachus’

Ocean Vuong talks about his work

Ocean Vuong reads ‘Queen Under the Hill’

Related News Stories

In 2023 the T. S. Eliot Prize celebrated its 30th anniversary. We marked the occasion by looking back at the collections which have won ‘the Prize poets most want to win’ (Sir Andrew Motion). Ocean Vuong won the T. S. Eliot Prize 2017 with his debut collection Night Sky With Exit Wounds (Cape...

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that this year’s winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2017 is Ocean Vuong for his remarkable debut collection Night Sky with Exit Wounds, published by Cape Poetry. After months of reading and deliberation, Judges W. N. Herbert (Chair), James...

To mark the 25th anniversary of the T. S. Eliot Prize, the T. S. Eliot Foundation has increased the winner’s prize money to £25,000. Judges W. N. Herbert (Chair), James Lasdun and Helen Mort have chosen the Shortlist from a record 154 poetry collections submitted by publishers. Tara Bergin, The...