Jacqueline Saphra’s first pamphlet, Rock’n’Roll Mamma, was published by Flarestack in 2008. Her first full collection, The Kitchen of Lovely Contraptions (flipped eye, 2011) was developed with funding from Arts Council England and nominated for the Aldeburgh First Collection Prize. A book of illustrated prose poems, If I Lay on my Back I Saw Nothing but Naked Women, was published...

Review

Review

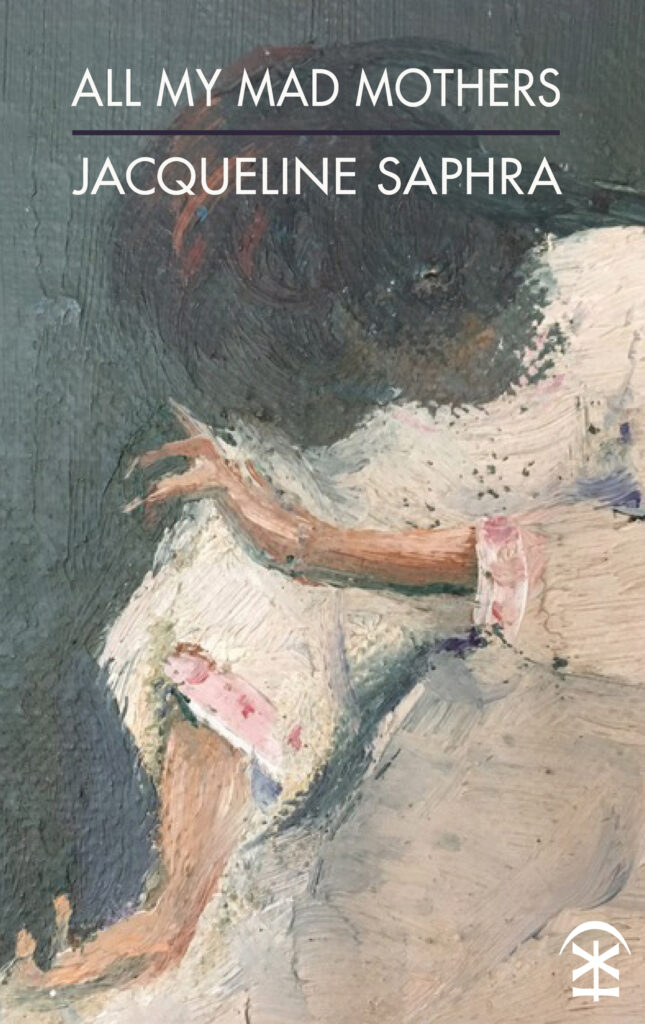

Jacqueline Saphra’s All My Mad Mothers is a moving rumination on motherhood, writes John Field. 'Interspersed with prose sketches, the collection is a warm and intimate exploration of love, sex, ageing and family'

Videos

Jacqueline Saphra reads from All My Mad Mothers at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Jacqueline Saphra reads ‘My Friend Juliet’s Icelandic Lover’

Jacqueline Saphra talks about her work

Jacqueline Saphra reads ‘My Mother’s Bathroom Armoury’

Jacqueline Saphra reads ‘Charm for Late Love’

Related News Stories

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that this year’s winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2017 is Ocean Vuong for his remarkable debut collection Night Sky with Exit Wounds, published by Cape Poetry. After months of reading and deliberation, Judges W. N. Herbert (Chair), James...

To mark the 25th anniversary of the T. S. Eliot Prize, the T. S. Eliot Foundation has increased the winner’s prize money to £25,000. Judges W. N. Herbert (Chair), James Lasdun and Helen Mort have chosen the Shortlist from a record 154 poetry collections submitted by publishers. Tara Bergin, The...