James Sheard was born in Cyprus in 1962, and spent his childhood abroad, mainly in Singapore and Germany. He is the author of three full collections of poetry: Scattering Eva (Cape Poetry, 2005), shortlisted for both the Forward Prize for Best First Collection and the Glenn Dimplex Award for Poetry, and Dammtor (Cape Poetry, 2010), as well as a poetry...

Review

Review

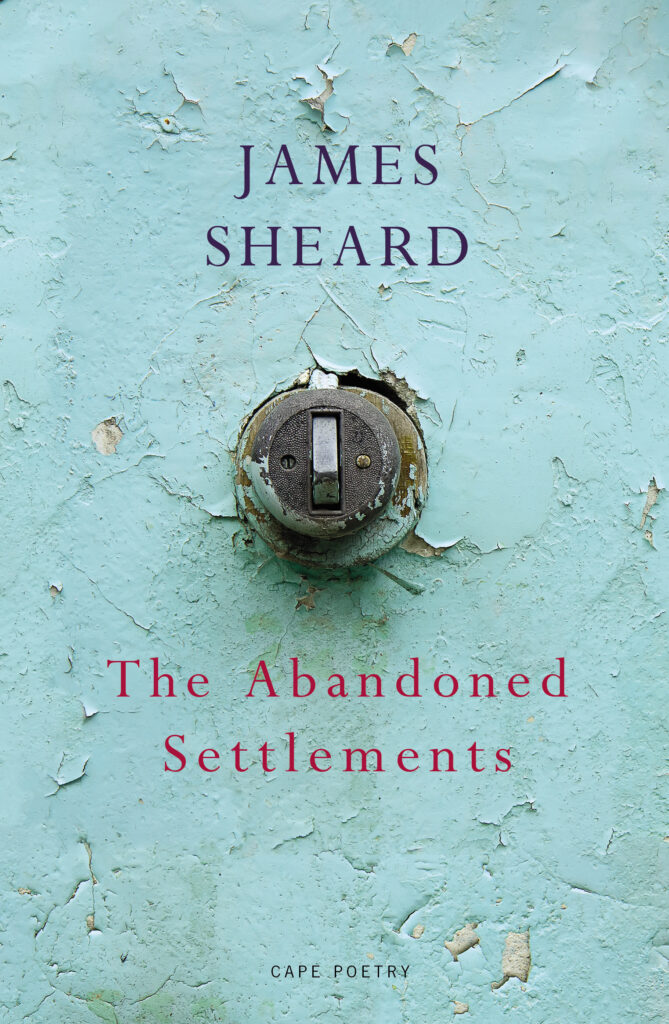

James Sheard’s The Abandoned Settlements 'views loss and change through the prism of place and space, and the result is painfully, exquisitely fragile', writes John Field

Videos

James Sheard reads from The Abandoned Settlements at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

James Sheard reads ‘Cardamom’

James Sheard reads ‘The Abandoned Settlements’

James Sheard talks about his work

James Sheard reads ‘Landings’

Related News Stories

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that this year’s winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2017 is Ocean Vuong for his remarkable debut collection Night Sky with Exit Wounds, published by Cape Poetry. After months of reading and deliberation, Judges W. N. Herbert (Chair), James...

To mark the 25th anniversary of the T. S. Eliot Prize, the T. S. Eliot Foundation has increased the winner’s prize money to £25,000. Judges W. N. Herbert (Chair), James Lasdun and Helen Mort have chosen the Shortlist from a record 154 poetry collections submitted by publishers. Tara Bergin, The...