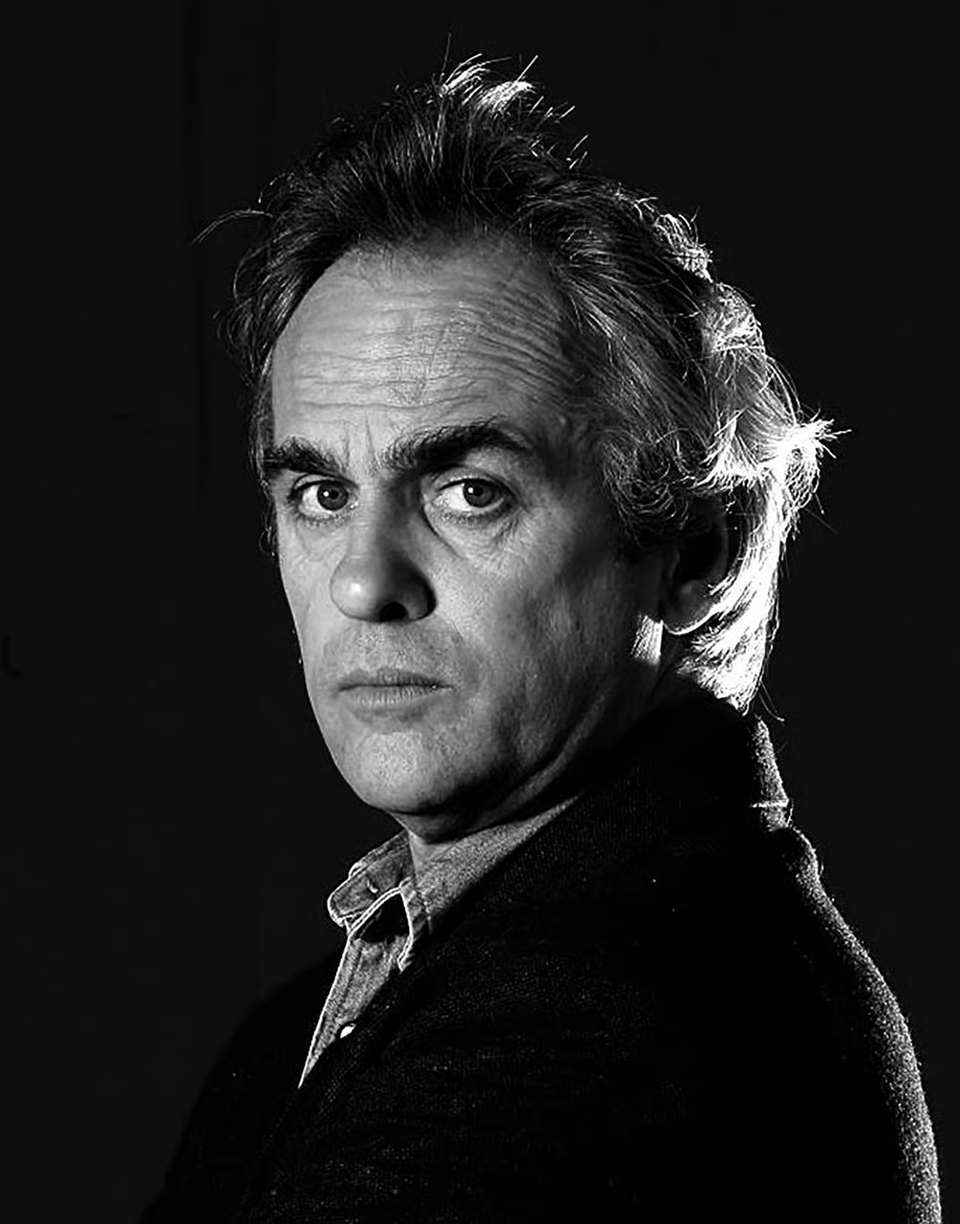

Robert Minhinnick was born in 1952 in South Wales, where he still lives. He is the prize-winning author of four volumes of essays, more than a dozen volumes of poetry and three works of fiction. His poetry collections include The Looters (1989) and Hey Fatman (1994), both published by Seren. A Selected Poems was published in 1999, followed by After the...

Review

Review

Robert Minhinnick's Diary of the Last Man 'presents an unsentimental, indifferent world, filled with cruelty and atrocity but, while there may be no Jesus in Minhinnick’s geology, there is no shortage of beauty', writes John Field

Videos

Robert Minhinnick reads from Diary of the Last Man at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Robert Minhinnick reads a section from ‘Mouth to Mouth: A Recitation Between Two Rivers’

Robert Minhinnick reads ‘After the Stealth Bomber: Umm Ghada at the Amiriya Bunker’

Robert Minhinnick talks about his work

Robert Minhinnick reads ‘London Eye’

Related News Stories

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that this year’s winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2017 is Ocean Vuong for his remarkable debut collection Night Sky with Exit Wounds, published by Cape Poetry. After months of reading and deliberation, Judges W. N. Herbert (Chair), James...

To mark the 25th anniversary of the T. S. Eliot Prize, the T. S. Eliot Foundation has increased the winner’s prize money to £25,000. Judges W. N. Herbert (Chair), James Lasdun and Helen Mort have chosen the Shortlist from a record 154 poetry collections submitted by publishers. Tara Bergin, The...