Michael Symmons Roberts was born in Preston, Lancashire, and spent his childhood in Lancashire. He now lives near Manchester. His eight poetry collections have all been published by Cape Poetry and include Corpus (2004), which was the winner of the 2004 Whitbread Poetry Award, and was shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize, the Forward Prize for Best Collection and...

Review

Review

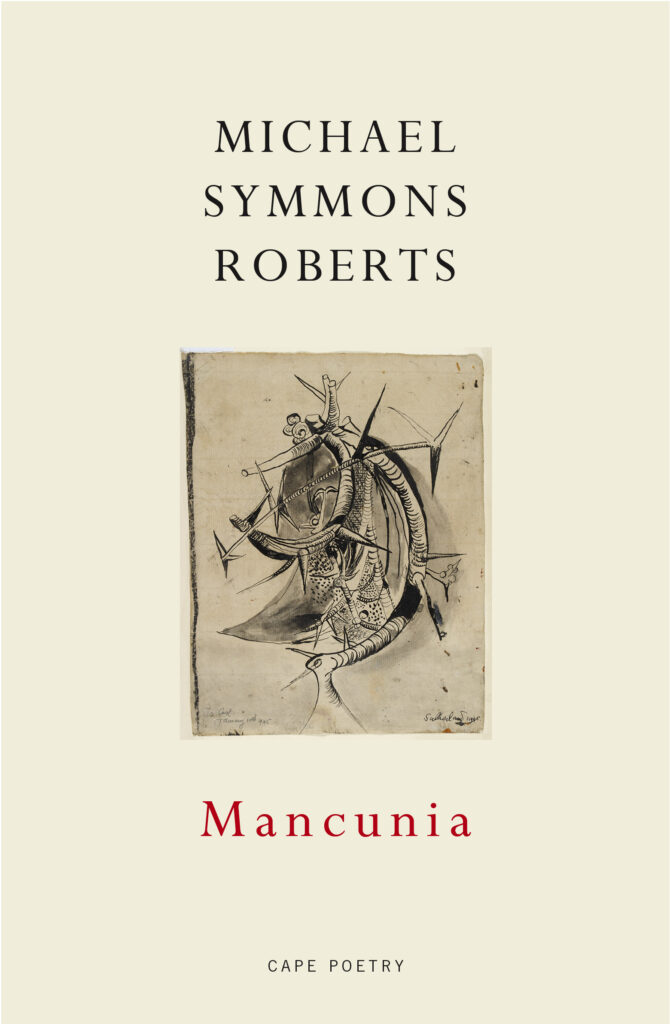

Michael Symmons Roberts's Mancunia explores the post-industrial identity crisis of urban spaces and of those who live in them, writes John Field. 'Yet, at the same time, Symmons Roberts sees a timeless optimism in the human spirit, that the utopian ambitions of our forbears live again through us'

Videos

Michael Symmons Roberts reads from Mancunia at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Michael talks about his work

Michael Symmons Roberts reads ‘What’s Yours is Mine’

Michael Symmons Roberts reads ‘Mancunian Miserere’

Michael Symmons Roberts reads ‘Barfly’

Related News Stories

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that this year’s winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2017 is Ocean Vuong for his remarkable debut collection Night Sky with Exit Wounds, published by Cape Poetry. After months of reading and deliberation, Judges W. N. Herbert (Chair), James...

To mark the 25th anniversary of the T. S. Eliot Prize, the T. S. Eliot Foundation has increased the winner’s prize money to £25,000. Judges W. N. Herbert (Chair), James Lasdun and Helen Mort have chosen the Shortlist from a record 154 poetry collections submitted by publishers. Tara Bergin, The...