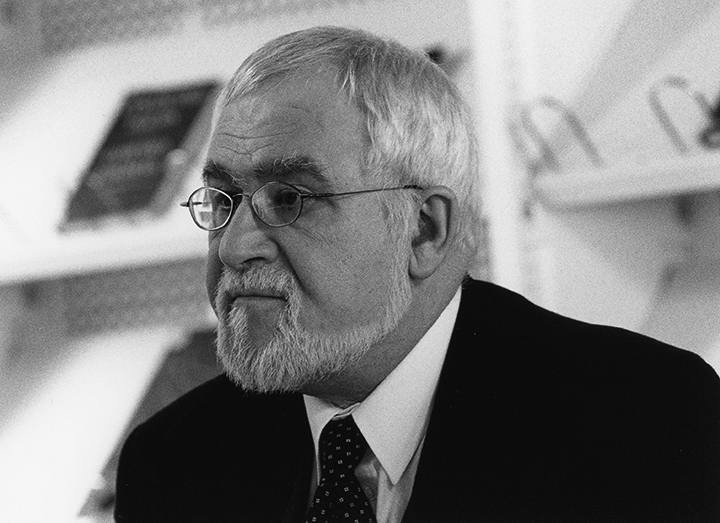

Douglas Dunn was born in Inchinnan, Renfrewshire, in 1942. He is a major Scottish poet, editor and critic, and the author of over ten collections of poetry published by Faber & Faber. His widely praised Elegies (1985), a moving account of his first wife’s death, became a critical and popular success and won the Whitbread Book of the Year Award...

Review

Review

Douglas Dunn's The Noise of a Fly is a frank exploration of ageing, writes John Field, but the collection has a political and social edge, with Dunn's eye trained on Scottish independence and the state of the NHS

Videos

Douglas Dunn reads from The Noise of a Fly at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Douglas Dunn reads ‘Idleness’

Douglas Dunn talks about his work

Douglas Dunn reads ‘Wondrous Strange’

Douglas Dunn reads ‘Class Photograph’

Related News Stories

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that this year’s winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2017 is Ocean Vuong for his remarkable debut collection Night Sky with Exit Wounds, published by Cape Poetry. After months of reading and deliberation, Judges W. N. Herbert (Chair), James...

To mark the 25th anniversary of the T. S. Eliot Prize, the T. S. Eliot Foundation has increased the winner’s prize money to £25,000. Judges W. N. Herbert (Chair), James Lasdun and Helen Mort have chosen the Shortlist from a record 154 poetry collections submitted by publishers. Tara Bergin, The...