Caroline Bird was born in 1986 and grew up in Leeds before moving to London in 2001. She won an Eric Gregory Award in 2002 and the Foyle Young Poet of the Year Award in 1999 and 2000. Caroline has had numerous collections of poetry published by Carcanet, including Looking Through Letterboxes (published in 2002 when she was only 15),...

Review

Review

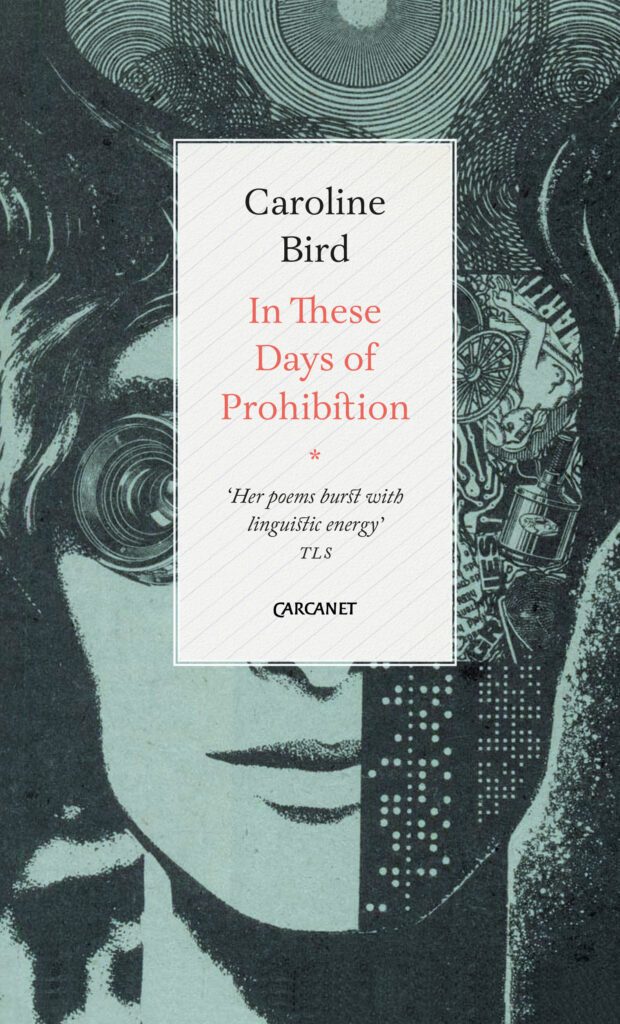

The poems in Caroline Bird's In These Days of Prohibition are profoundly disquieting, exploring obsession, hedonism and anxiety, writes John Field

Videos

Caroline Bird reads from In These Days of Prohibition at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Caroline Bird reads ’48 Veneer Avenue’

Caroline Bird reads ‘Patient Intake Questionnaire’

Caroline Bird reads ‘Megan Married Herself’

Caroline Bird talks about her work

Related News Stories

The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that this year’s winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2017 is Ocean Vuong for his remarkable debut collection Night Sky with Exit Wounds, published by Cape Poetry. After months of reading and deliberation, Judges W. N. Herbert (Chair), James...

To mark the 25th anniversary of the T. S. Eliot Prize, the T. S. Eliot Foundation has increased the winner’s prize money to £25,000. Judges W. N. Herbert (Chair), James Lasdun and Helen Mort have chosen the Shortlist from a record 154 poetry collections submitted by publishers. Tara Bergin, The...