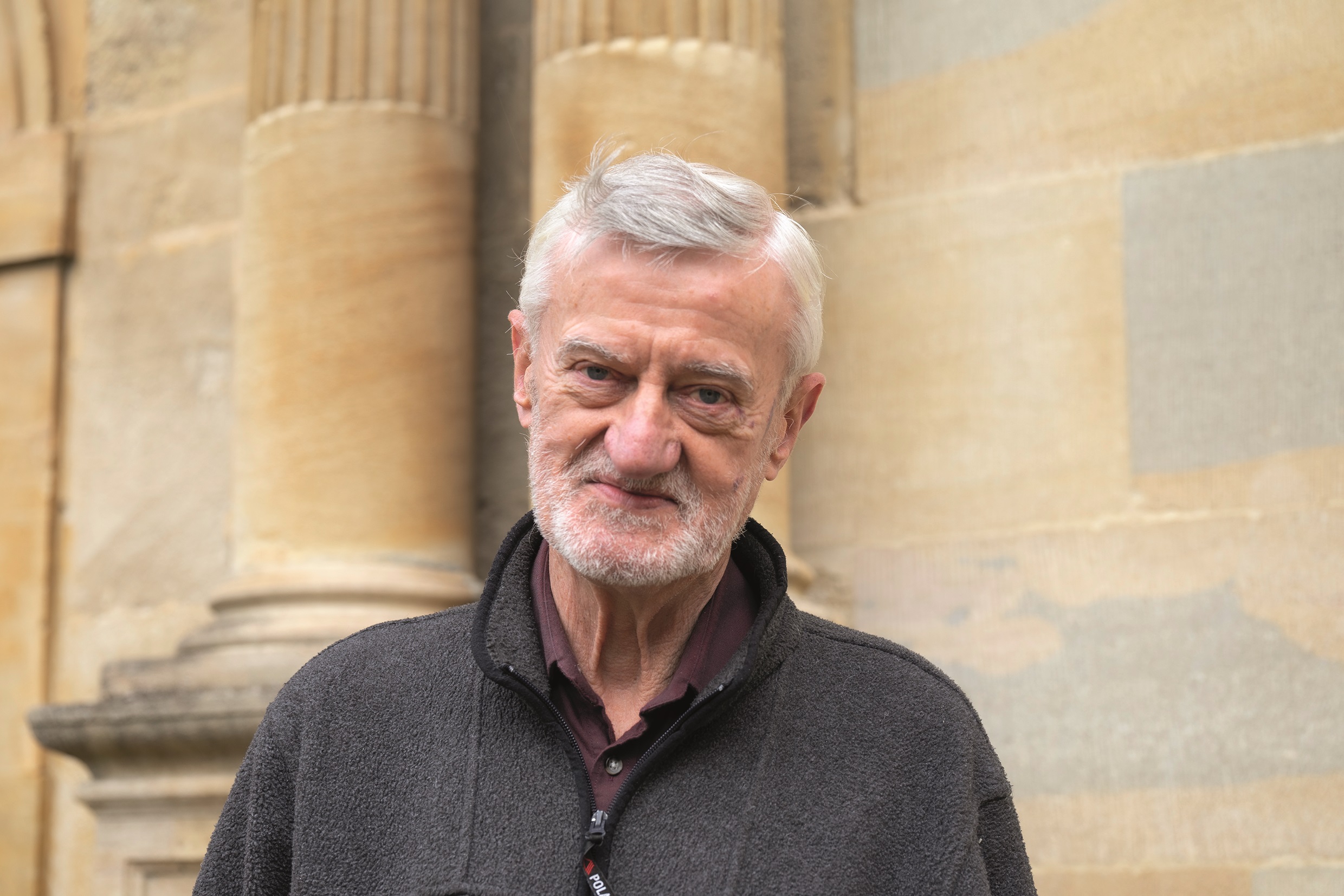

Bernard O’Donoghue was born in Cullen, Co Cork in 1945, later moving to Manchester. He is an Emeritus Fellow of Wadham College, where he taught Medieval English and Modern Irish Poetry. He has published six collections of poetry, including Gunpowder (Chatto & Windus), winner of the 1995 Whitbread Prize for Poetry, and Farmers Cross (Faber & Faber), which was shortlisted...

Review

Review

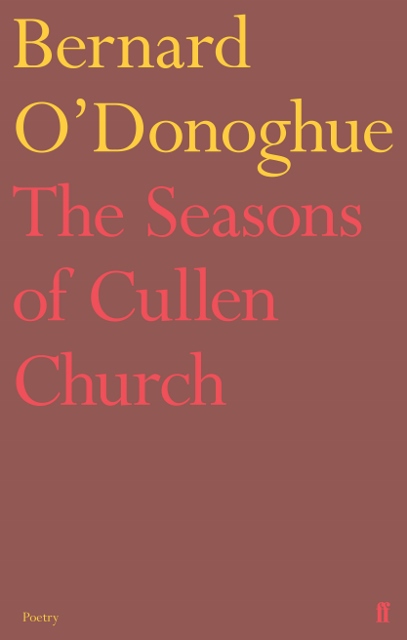

'If you enjoyed Heaney's final collection, Human Chain, then you are likely to enjoy The Seasons of Cullen Church [...] Translations of Dante, the Gawain Poet and William Langland allow these poems to resonate with the whole authority of the language – pure, beautiful and true', writes John Field

Videos

Bernard O’Donoghue reads from The Seasons of Cullen Church at the T. S. Eliot Prize Shortlist Readings

Bernard O’Donoghue reads from The Seasons of Cullen Church

Bernard O’Donoghue reads his poem ‘Munster Final’

Related News Stories

Jacob Polley’s disturbing tale of lost innocence wins world’s most prestigious poetry prize The T. S. Eliot Foundation is delighted to announce that the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize 2016 is Jacob Polley for his remarkable new collection Jackself. After months of reading and deliberation, judges Ruth Padel...

To help readers engage fully with the T. S. Eliot Prize 2016 Shortlist, we asked poetry blogger and regular Eliot Prize reviewer John Field to explore the shortlisted titles. In his review of Rachael Boast’s Void Studies, John Field writes, ‘Reading Void Sudies is a sensual, sensory joy. Like music,...

The T. S. Eliot Prize is delighted to announce the thrilling 2016 Shortlist, featuring exciting newcomers and established names. Judges Ruth Padel (Chair), Julia Copus and Alan Gillis have chosen the Shortlist from 138 books submitted by publishers: Rachael Boast – Void Studies (Picador Poetry) Vahni Capildeo – Measures of...